In the 2016 Census of population, 240,615 people reported being of Vietnamese origin (including single and multiple ethnic-origin responses). In addition, a few tens of thousands of Canadians reported being of Chinese origin but actually came from Vietnam. Like the majority of the Canadian population who were born abroad, Canadians of Vietnamese origin have settled mainly in Canada’s metropolitan areas and other urban communities. Slightly more than 166,000 Canadians reported Vietnamese as their mother tongue (Vietnamese ranks fourteenth among immigrant languages in Canada).

Vietnamese have integrated well into Canadian society and contributed to the country’s political, cultural and sporting life. Notable Canadians of Vietnamese origin include concert pianist Dang Thai Son, who won first prize at the International Fryderyk Chopin Piano Competition in 1980; Thanh Hai Ngo, the first Vietnamese Canadian appointed to the Senate; Eve-Mary Thai Thi Lac, federal member of Parliament for Saint-Hyacinthe-Bagot, Québec and the first Vietnamese Canadian woman elected to the House of Commons; filmmaker and activist Paul Nguyen; UNESCO goodwill ambassador Kim Phúc; writer Kim Thùy; and Carol Huynh, who won the gold medal for women’s freestyle wrestling at the 2008 Olympic Summer Games in Beijing and the bronze medal in her division at the 2012 Summer Games in London.

Overview

Located in mainland Southeast Asia, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is bordered by China, Laos and Cambodia, and has an extensive coastline along the South China Sea and the Gulf of Tonkin (see Southeast Asian Canadians). After nearly a century of French colonial influence and seven years of war, Vietnam gained independence in 1954. The conflict left the country politically divided between the Communist north and the Western-oriented south. In 1965, the United States began to send troops to assist the South Vietnamese, marking the beginning of the second Vietnam War.

In 1975, the North Vietnamese, supported by China and the Soviet Union, successfully forced out the Americans and reunited the north and south under Communist rule. Today, although Vietnam remains a single-party state, it is considered a post-socialist nation and has liberalized its economy to promote growth and development. It is still primarily an agricultural nation with a population that is largely Buddhist and approximately 87 per cent ethnic Vietnamese.

Immigration History

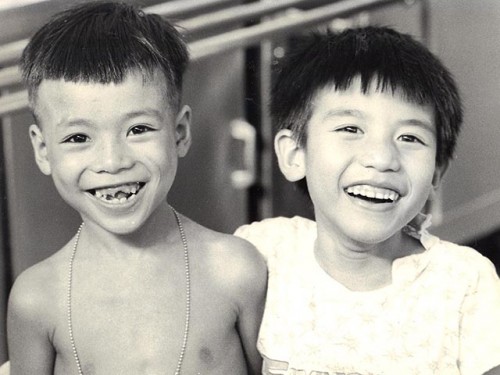

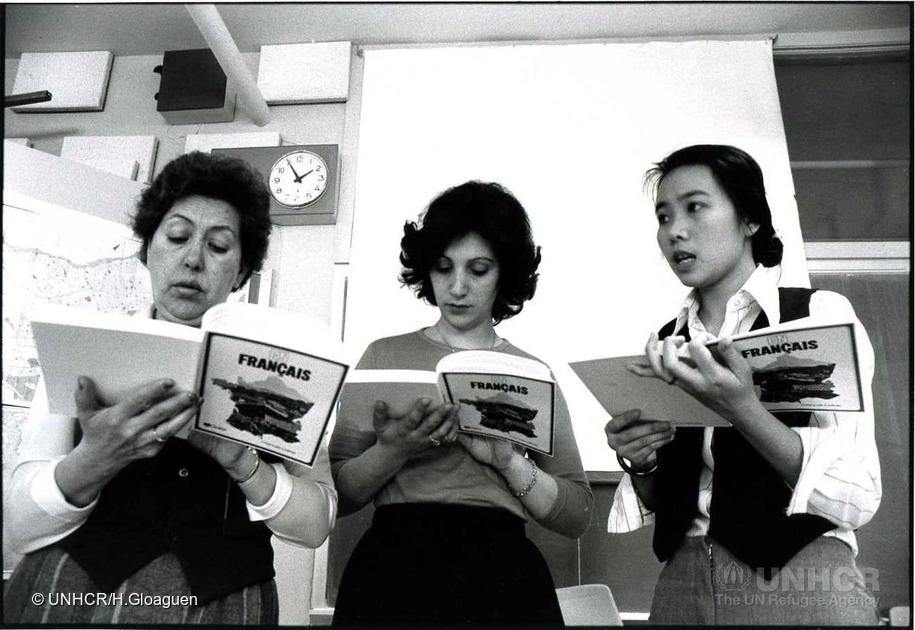

Migration from Vietnam to Canada has occurred in two waves. The first wave began in 1975, after it became clear that South Vietnam would be taken by the Communists. The Vietnam War ended on 30 April 1975 with the fall of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, to Communist forces. Fearing reprisal for their support of the United States or South Vietnam, many sought an escape from the country. Canada admitted 5,600 Vietnamese between 1975 and 1976 as political refugees. These immigrants consisted primarily of middle-class people who were accepted into Canada due to their professional skills or because they had family members in Canada to act as sponsors. Many spoke French, or sometimes English, as a second language.

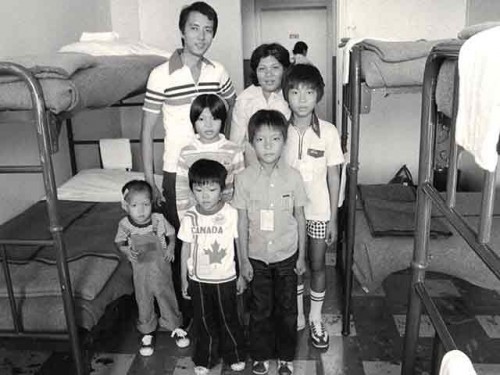

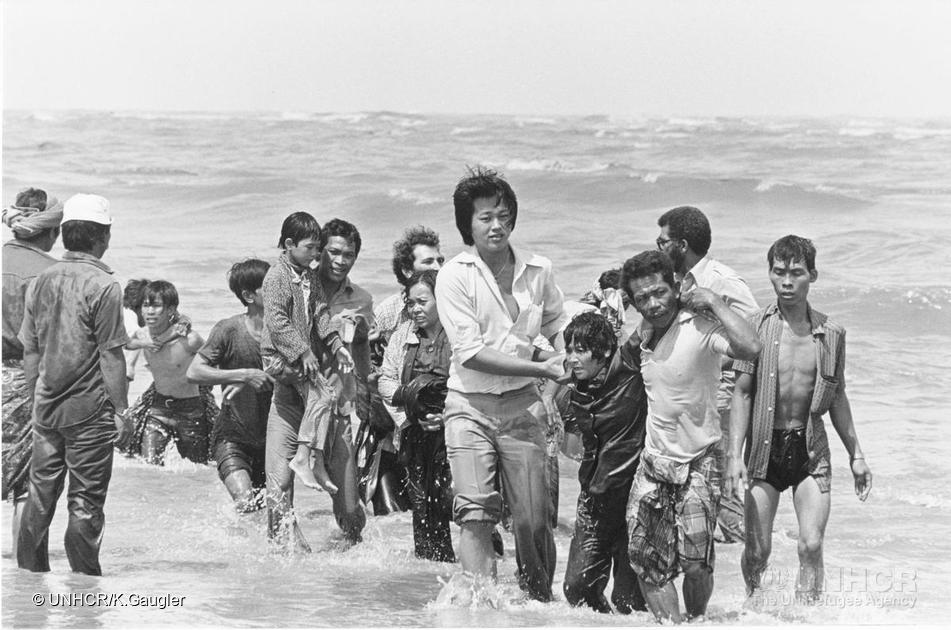

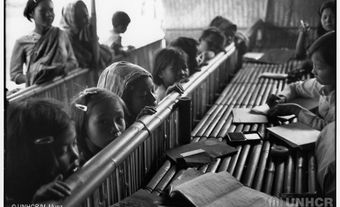

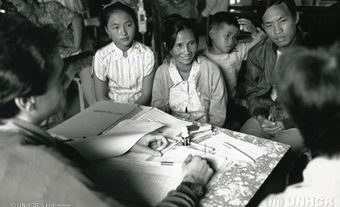

The second wave occurred in two stages. The first took place between 1979 and 1982 and consisted of South Vietnamese refugees who suffered under the harsh conditions of the new Communist regime. This group was much more diverse than the first wave, consisting of immigrants of a wide variety of socio-economic standings and ethnicities (namely several thousand Vietnamese of Chinese origin), from both urban and rural areas. These refugees were often referred to as “boat people” because many made the dangerous journey from Vietnam on over-crowded makeshift boats to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) camps in places such as Hong Kong, Malaysia and Indonesia. An estimated one-third of the refugees who escaped by boat did not survive the journey.

Canada was one of the main resettlement countries, accepting more than 60,000 Southeast Asian refugees during these years. More than 50 per cent of these refugees came to Canada as a result of a brand-new private sponsorship program put in place by the government. It was therefore in large part due to the efforts of Canadian families, religious communities, charitable organizations and non-governmental organizations that these people had the opportunity to rebuild their lives in Canada.

The second stage began in 1982 and continues today. This stage is referred to as “continuous flow” immigration, consisting of migrants from overseas refugee camps, those immigrating through Vietnam’s Orderly Departure Program, and those arriving through the efforts of Vietnamese Canadians to reunite their families.

On 13 November 1986, in recognition of its exceptional contribution to refugee protection, Canada was awarded the Nansen Medal by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Governor General Jeanne Sauvé accepted the honour on behalf of the “People of Canada.” It is the only time the honour has been bestowed on an entire population. The medal is kept at Rideau Hall.

In 2015, the Parliament of Canada passed the Journey to Freedom Day Act, which designated 30 April as a national day of commemoration of the exodus of Vietnamese refugees and their acceptance in Canada after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War.

Settlement Patterns

According to Statistics Canada, there are 240,615 persons of Vietnamese origin in Canada. They live primarily in urban centres in Ontario, Québec, British Columbia and Alberta. When the suburbs are included, the population of Vietnamese origin is 73,745 in the Greater Toronto Area, 38,660 in the Montréal Urban Community, 34,915 in metropolitan Vancouver and 21,010 in the Calgary region.

Because Vietnamese are fairly recent migrants to Canada, the majority are first-generation Canadians who were born in Vietnam. Less than two out of five were born in Canada, whereas 70 per cent, including non-permanent residents, were born abroad.

Socio-economic Data

Vietnamese Canadians work in many different sectors of Canada’s economy, notably manufacturing and scientific and technical occupations. Many Vietnamese Canadians are also entrepreneurs, owning and operating businesses such as restaurants and grocery stores. They tend to have the same employment rate as the Canadian average, but their incomes are notably lower.

In 2011, Québec’s Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities reported that out of all Vietnamese Quebecers who were active in the labour market, 29.2 per cent worked in sales and services, 15.1 per cent in business, finance and administration, 13.3 per cent in natural and applied sciences, and 11.3 per cent in the health sector. Overall, Quebecers of Vietnamese origin have an average income of $33,674, still less than the average of $36,352 for the Québec population as a whole.

Social, Cultural and Religious Life

There is concern among the Vietnamese Canadian community that Vietnamese cultural values and practices such as religion and language be maintained. To prevent cultural erosion, formal networks such as the Vietnamese Canadian Federation, as well as informal social networks, assist the community in maintaining its cultural identity.

According to the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS), approximately half of all Vietnamese Canadians identify as Buddhist, while more than a quarter identify as Christian and the remaining quarter or so said they had no religious affiliation. There are Vietnamese Buddhist temples and Christian churches in cities across Canada. Temples and churches alike play an important role, not only in religious practices, but also in celebrating Vietnamese holidays, performing weddings and funerals, and organizing other social gatherings.

According to the Canadian Census, 166,830 people reported Vietnamese as their mother tongue in 2016. That's 13,475 more people than in 2011. However, Vietnamese ranks fourteenth among immigrant languages in Canada.

Bilateral Relations between Canada and Vietnam

In 2013, Canada and Vietnam celebrated 40 years of bilateral relations. Many activities were organized to highlight the important anniversary. Canada established diplomatic relations with Vietnam in 1973, opened an embassy in Hanoi in 1994 and opened a consulate general in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) in 1997. The 1986 economic reforms in Vietnam (referred to as “Doi Moi” or renewal) have led to economic and social changes, and Canada and Vietnam have strengthened their economic partnerships through such organizations as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Over the past 10 years or so, bilateral trade between Canada and Vietnam has grown steadily. It is now four times higher than in 2000. In 2013, it reached an all-time high of nearly $2.6 billion.

Trade between Canada and Vietnam

Trade commissioners in both countries assist business representatives and entrepreneurs to navigate trade agreements. Regular visits by government officials have strengthened the bonds and opportunities in both countries and offered expertise in a variety of business opportunities. In 2010, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) attended the G20 conference in Toronto, followed by Canada’s minister of Foreign Affairs attending two ASEAN conferences in Hanoi. Canada and Vietnam use their affiliation with organizations such as ASEAN, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the ASEAN Regional Forum, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie and the United Nations to improve and expand economic opportunities. Today, Vietnam’s annual economic growth is one of the largest in Asia.

Social Benefits of Trade

The relationship between Canada and Vietnam not only focuses on economic development but also involves attention to social conditions in Vietnam, including the rights to freedom of expression and association. In 2014, Vietnam became one of the countries targeted by the government of Canada for international development efforts. The Vietnamese government’s priorities of reducing poverty by establishing a good investment climate and supporting rural business development are consistent with the objectives of Canada’s current cooperation and development program. Global Affairs Canada is the main department that provides humanitarian assistance and support for sustainable development. In 2010, following severe flooding in Vietnam, the Canadian International Development Agency (which merged with the Department of Foreign Affairs in 2013) committed $50,000 to emergency relief operations, including distribution of non-food relief items, drinking water and community support.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom