Sports have a long history in Canada, from early Indigenous games (e.g., baggataway) to more recent sports such as snowboarding and kitesurfing. Starting in the late 19th century, sports became more organized, including the development of various national organizations, and many Canadian men participated in sports including lacrosse, baseball, hockey, rugby/football and soccer. Women’s participation in sports was limited until the 1960s, when sports previously considered “manly” began to open to girls and women (see also History of Canadian Women in Sport). Officially, Canada has two national sports: lacrosse (summer) and hockey (winter).

Indigenous Game and Sport

Canadian sport is indebted to Indigenous culture for the toboggan, snowshoe, lacrosse stick and canoe. The coureurs des bois and the voyageurs, through their close contact with Indigenous peoples, helped introduce into European settlements the activities that resulted from the use of these pieces of equipment. Many Indigenous games had utilitarian purposes related to survival (e.g., wrestling, archery, spear throwing, and foot and canoe racing), while activities such as dancing and baggattaway (see Lacrosse) had religious significance. First Nations also developed a great variety of games, such as awl games, ring and pole, snow snake, cat's cradle, dice and birchbark cards, partly for the sheer love of play and sometimes for the purpose of gambling. The games of the Inuit were similarly related to preparing youth for co-operative existence in a harsh environment where one also needed to know one's tolerance limits. Blanket toss, tug-of-war, dogsled races, drum dances, spear throwing and ball games, as well as self-testing games such as arm-pull, leg-wrestling and finger-pull, helped to fulfil this purpose.

European Colonization

In European pioneer settlements, play was relatively unimportant compared with the serious work of survival, yet social and recreational activities were necessary and did occur. French Canadians inherited their love of social gatherings from France. North America's first Caucasian social club, the Ordre de Bon Temps, was formed at Port-Royal. Social gatherings in pioneer societies, in the form of "bees" (husking, quilting and barn raising), also had a utilitarian basis, as participants could benefit from co-operative labours. Such gatherings usually offered music and dancing, wrestling and horse racing, and provided opportunity for the "strong man" tradition to develop in French Canada, exemplified later in Louis Cyr.

With the Seven Years War (1755–63) came an influx of British soldiers and settlers. Scattered across the provinces in garrisons, British soldiers brought with them cricket and equestrian sports, while the Scots in particular introduced golf and curling to North America. Although golf did not become an established sport before Confederation, curling quickly became popular in Canada. The first sporting club, founded in 1807, was the Montreal Curling Club. Golf's initial failure and curling's success serve to demonstrate the relationship between sport and society. In the early period, the large tracts of land required to maintain a small number of golfers were an unaffordable luxury, whereas in the Canadian winter ice was plentiful and accessible to all.

19th Century Sport and Society

In the early 19th century, the majority of active sportsmen were gentlemen players from the merchant or upper strata of society and garrison officers. Not only did these officers re-establish the sporting traditions of their homeland in their new environment, but they were also eager to adopt and sponsor new activities. Their love of horse racing, along with their leisured existence, gave impetus to such sports as hunting, trotting and steeplechasing. Their all-encompassing interest and enthusiasm, combined with their managerial expertise, resulted in a broad spectrum of sport being established within communities.

In theory, skating, snowshoeing, cricket, football (soccer) and similar activities were available for the working class; however, this group lacked time for sporting and recreational activities. For many, Sunday was the only day of rest, but they were deterred from sporting activities on that day by religious groups and by the Lord's Day Act, which was passed in 1845 in the Province of Canada.

Most pioneer women were far too busy to enjoy much leisure, but even when the opportunity presented itself, the conventions of the time prevented their active participation in most of the outdoor recreational activities followed by men. In the cities, their passive involvement was encouraged through attendance at horse races, regattas, cricket matches and other spectator sports. It was permissible for them to be passengers in carrioles, iceboats and yachts; the more fortunate and independent were allowed to ride horses, skate or play croquet. The 1850s witnessed a change in attitude towards women engaging in sport that was also aided by changes in sporting attire. Female participation in fox hunting, the Ladies' Prince of Wales Snowshoe Club (1861), the Montreal Ladies Archery Club (1858), rowing regattas, figure skating championships and foot races at social picnics was evidence of growing emancipation. (See also History of Canadian Women in Sport.)

Probably the greatest role sporting competition played prior to 1867 was as social gathering and mixing ground. City and country dwellers could meet at the agricultural-social events; voyageurs could compete with Indigenous people and settlers at canoe regattas; First Nations people could engage townsfolk in lacrosse. Race meetings were very popular and attracted thousands of spectators in the large urban centres. Horse racing provided a social as well as sporting environment for the townsfolk and was the setting for the greatest social mingling of 19th-century society. The upper classes tended to resist this mingling, however, and made unsuccessful efforts to preserve horse races for themselves by erecting fences around the courses and charging admission. This exclusion policy may also be seen in the appearance of events for "gentlemen amateurs" in regattas and horse races, ensuring that the practised fisherman rower or the skilled farmhand could not compete with the social elite.

Industrialization and Urbanization

The greatest impact upon sports came from advances in technology. The steamboat, railway locomotive and steam-powered printing press made it possible for sport to be brought before the public. Steamboats carried sporting teams and spectators on excursions that had previously been highly impractical by stagecoach. They even followed the boats and yachts during regattas. The rapid expansion of railways made the one-day excursion for match play feasible (see Railway History). More widely represented team meetings and bonspiels could be arranged, provincial associations formed and rules of play were made more uniform. The larger newspapers, made possible by steam-powered printing presses, carried greater sports coverage, and the invention of the telegraph brought quicker reporting of results.

Sport, by Confederation in 1867, was approaching a new era. Old activities such as cricket, rowing and horse racing continued to be important, while the emergence of sports such as lacrosse and baseball was the mark of a country with expanding sporting interests. With urbanization came the realization among civic leaders that the population needed healthy diversion and exercise. These two forces contributed to the increased organization of sporting activities.

Organization and Nationalism

From about the middle of the 19th century, there was a concerted effort to regulate and organize sport. Montréal led much of this development, establishing a number of sporting organizations, e.g., the Montreal Lacrosse Club, Montreal Snow Shoe Club and Montreal Cycling Club. William George Beers, a Montréal dentist, was the driving force behind the development of modern lacrosse and the formation of the National Lacrosse Association on 26 September 1867, at a convention in Kingston, Ontario — this was the first of many such sports organizations to be established in Canada. The Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (established 1881) was the first club of its kind, and acted as an umbrella for many sports clubs in that city. It was a social as well as a sports centre, with a large building providing reading and meeting rooms, a gymnasium and, eventually, a swimming pool. This club was the driving force behind the formation of the Amateur Athletic Association of Canada (1884), the first attempt to unify and regulate all sport in the country.

The late 19th century also witnessed an emerging Canadian identity in sport. Sport played an integral part in the development of national feeling, at least among English-speaking Canadians. This trend is clearly seen in the development of lacrosse, which saw phenomenal growth in the summer of 1867 (from six to 80 clubs); that year, William George Beers attempted (unsuccessfully) to have the sport proclaimed Canada's national game. The unifying force of sport was also clearly shown when all of Canada basked in the glory achieved by the “Paris Crew”, a rowing team from Saint John, New Brunswick, that won the world championship at the Paris Exhibition in France in 1867.

Sports in Late 19th Century

Sport was intensely creative and exciting in the late 19th century. Canadians were at the forefront of the development and popularization of lacrosse, baseball, football, hockey and basketball. In 1891, Canadian James Naismith invented the game of basketball while teaching in Massachusetts. The game spread, and was soon played in Canada.

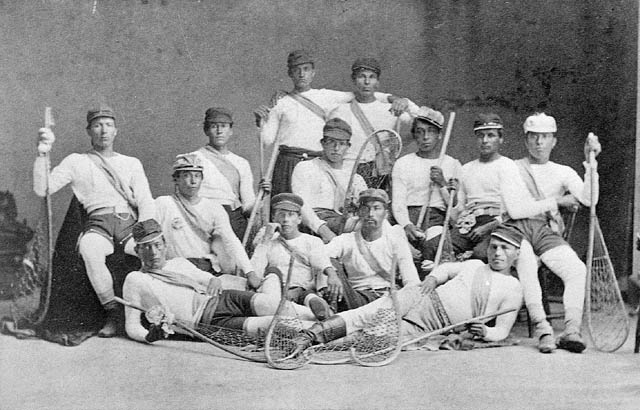

Lacrosse was so popular in the 1880s that the myth grew that it had been declared, by Act of Parliament, to be the national game. By the 1880s the game had been introduced to England and was spreading to Western Canada.

Eventually baseball would challenge lacrosse for public support and interest as a summer sport. The Canadian Baseball Association was formed in 1876 and the first baseball leagues shortly thereafter. Much of baseball's early success occurred in southwestern Ontario, where the proximity of the United States was enhanced by railway links.

Football, too, had a rapid evolution in this period. In 1874, Canadians introduced their American neighbours to the oval ball and rules of rugby. That year also marked the beginning of a series of annual matches between McGill and Harvard universities. As a result, the Americans shifted away from association football (called soccer today in North America), and adopted the oval ball and scrum of rugby. By the turn of the 20th century, the game had evolved into what North Americans now call “football.” The links of the game to the universities and colleges of both countries contributed to its longstanding success. In Canada, the sport was largely based in Ontario and Québec, and, in 1884, the first national football championship was held.

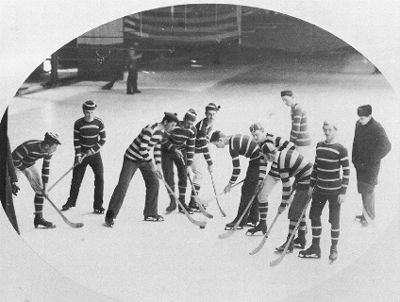

Both rugby and lacrosse contributed to hockey's evolution from an ill-defined version of British stick and ball games. Many of its practices, including the face-off, its regulations concerning offsides and the use of goals to score points, were borrowed from the other sports. By the turn of the century, hockey was replacing lacrosse as Canada’s most popular game.

Amateurism vs. Professionalism

It is clear that the thrust behind the organization of sports in Canada's cities at this time came from members of the professional and business classes, who had the contacts, organizational drive and time to devote to this development. Faith in a scientific approach to all matters in life helped shape their attitudes to sport. One result of this approach, besides the development of sports organizations, was a fervent belief in amateurism and amateur codes.

At the beginning of the 19th century, sport was largely controlled by the upper classes, and restrictive codes were established to segregate undesirables; the earliest forms were often racially based, restricting Indigenous and Black people from competing with White people. Eventually, as the working classes gained more free time, there arose the desire to restrict them too. It was not until early closing hours for shops and factories became more widespread in the mid-1860s that working class participation in sport became possible. In this context, the advent of lacrosse and baseball was timely, although even these sports tended to exclude members of the lower class, or "rowdies" as they were called, from organized teams. Where an activity was dependent upon organization, it still remained largely the prerogative of the affluent members of society.

Having the time to develop strength and skills became a determinant, but eventually it was money, which released one from having to find other means of livelihood, that separated the amateurs from the professionals. The Amateur Athletic Association of Canada, in 1884, defined an amateur as being "one who has never pursued, or assisted in the practice of manly exercise as a means of obtaining a livelihood." According to this code, professional athletes were highly suspect and held in very low regard.

The man who contributed most to changing these attitudes was Toronto's great Ned Hanlan, the world's professional sculling champion (1880–84). Thousands travelled great distances on special excursions arranged by railway promoters to watch him row against the world's best. He became the focus of a growing national spirit and helped to create a broad public acceptance, indeed adulation, for those who possessed great athletic skills. Deriving commercial benefit from his talent was simple affirmation of his ability.

Among those that continued in the amateur tradition were Louis Rubenstein and George Orton. Rubenstein won the unofficial world championship in figure skating in 1890 and eventually became a pillar in the development of that sport, and in others like cycling. Orton became the first Canadian champion in the modern Olympic Games, the great forum for the amateur athletic ideal. Canada sent no representative to the first Olympics, held in Greece in 1896, but Orton won the 2500 m steeplechase event at the second Olympics in 1900.

As Canada entered the 20th century, the amateur ethic was strong and would remain the basis for much athletic participation, but the door was open for professional sports where public interest made it commercially viable. Moreover, Canadians had found success and pride in challenging athletes from other parts of the world.

Growth of Professional Sports

urbanization and industrialization, which had helped sow the seeds of modern sport in the 19th century, continued into the 20th century with even greater impact. One result was the full maturing of professional sports into great commercial spectator attractions.

hockey's roots were firmly planted in Canada and it was rapidly replacing lacrosse as the "national game." By 1908, it epitomized the divergent trends of sports towards amateurism and professionalism. The Stanley Cup became emblematic of the professional championship, and the Allan Cup and Memorial Cup of the amateur championships. After the Second World War, first through Foster Hewitt's radio broadcasts and later through television, professional hockey gained an almost mesmerized national audience. Professional hockey has continued to be Canada's most popular sport and the sport most associated with the national identity.

Lacrosse, in contrast, dropped from being by far the most popular sport of the first decade, in number of spectators and press attention, into a state of serious decline by the 1920s. The press of the day was critical of the recurring violence in lacrosse matches. The game failed to develop a system of minor leagues that could produce future talent. Furthermore, it was a summer sport and the arrival of the automobile enabled people to escape the hot cities to other forms of recreation. Finally, the media lost interest in lacrosse, turning their attention to baseball, with its "big league" glamour.

Despite baseball's popularity as a summer sport, it took nearly 70 years before a major league franchise was established in the country. However, a number of Canadian cities had teams in the "Triple A" International League, including Toronto, Montréal, Hamilton, Ottawa and Winnipeg.

Softball (fast-pitch and slow-pitch)also became popular in Canada. The Toronto Tip Top Tailors (or Tip Tops) claimed the world softball championship in 1949 and the Richmond Hill Dynes repeated this feat in 1972.

With the formation of the Montreal Expos in 1969 and the Toronto Blue Jays in 1977, two Canadian cities had franchises in the American-based professional major leagues of baseball. The Blue Jays made major league history by winning the World Series in 1992. They were the first non-US resident team to achieve this. They repeated their championship in 1993.

Football was another sport that experienced healthy growth in the 20th century, evolving from a game with a large amateur base into a highly commercialized sport played by professionals. Until the mid-1920s, the game was dominated by university teams (e.g., University of Toronto, Queen’s University). However, after that time the emphasis on amateurism declined, and the stronger city-based teams became dominant. Moreover, once the forward pass became part of Canadian football in 1931, teams started to import players from the United States (the forward pass had been part of American football for years).

Nevertheless, Canadian football has retained its unique flavour and has enjoyed the status, in its own season, of a major commercial endeavour capable of drawing widespread public interest. One of the reasons for this is the East versus West rivalry that the game has generated. This began in 1921, when the Edmonton Eskimos first provided a western challenge for the Grey Cup. In 1935, Winnipeg won the national championship, a first for a western team. In 1948, the antics of Calgary fans in Toronto started the idea for a full-blown festival associated with the Grey Cup game.

Canada also has teams in professional basketball and soccer leagues. In 1995, Canada gained two franchises in the National Basketball Association: the Toronto Raptors and the Vancouver Grizzlies (who relocated to Memphis in 2001). The country also boasts three teams in Major League Soccer: the Vancouver Whitecaps, Toronto FC and Montréal Impact.

International Competition

A significant development of the 20th century was the growth of competitive opportunities for Canadians against athletes from around the world. As success in international events became of increasing importance, it came to be seen as part of the "national interest" to support athletes with government assistance.

Canada has entered an official team at the Olympic Games since 1908, except for the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games (see Olympic Summer Games and Olympic Winter Games). Hamilton, Ontario, was the host for the first British Empire Games (later the Commonwealth Games) in 1930 and the Pan American Games were started in 1951. All three multi-sport festivals provide a highly visible international stage on which amateur athletes can focus their training programs and aspirations for success.

Canadians have also excelled in Paralympic sport. The international Paralympic movement gained strength in the 1960s in an attempt to promote inclusivity in competitive sport, and Canadian athletes were active competitors early on. During the first Paralympic Games in Rome in 1960, 400 athletes with spinal cord injuries from 23 countries competed, Canadians among them. The International Paralympic Committee was founded in 1989, and Canadian Robert Steadward, an expert in the field of disabled sport, was elected president.

Women and Sport

One of the most significant developments of the 20th century was the growth of women’s sports. As part of the women’s movement, women challenged gender restrictions in sport, as in other areas of life. Since then, the number of female athletes has increased dramatically and many Canadian women have excelled in sports such as track and field, swimming, diving, hockey, rowing, cycling, gymnastics, skiing, speed skating, soccer and wrestling (see History of Canadian Women in Sport).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom