Sir Frederick Grant Banting, KBE, MC, FRS, FRSC, co-discoverer of insulin, medical scientist, painter (born 14 November 1891 in Alliston, ON; died 21 February 1941 near Musgrave Harbour, Newfoundland). Banting is best known as one of the scientists who discovered insulin in 1922. After this breakthrough, he became Canada’s first professor of medical research at the University of Toronto. Banting was also an accomplished amateur painter. As an artist, he had links to A.Y. Jackson and the Group of Seven.

Education and Early Career

Frederick Banting was the youngest of six children. His parents were William Thompson Banting and Margaret Grant. His father’s extended family was of British descent and Methodist faith. They were hard-working, straight-laced and prosperous farmers. The family lived in the Alliston area, about 60 km north of Toronto, Ontario.

Banting enjoyed a normal boyhood on the farm. Shy and studious, he completed high school and entered the University of Toronto. He had the vague idea of becoming a Christian minister. After failing the first year of a general arts course, he shifted focus. He enrolled in the faculty of medicine. Admission standards for medical students were not as high as they are now.

Banting was a quiet, unremarkable medical student. His grades were slightly above average. He later claimed his medical education was extremely lacking. One reason for this was that his class of 1917 was condensed into a shorter final year. It graduated in 1916 because of the urgent need for doctors to serve in the First World War. As a student, Banting had enlisted in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Upon graduation, the Corps sent him abroad to serve as a medical officer.

First World War

Frederick Banting worked in military hospitals in England. This work sparked his interest in surgery and research. In the summer of 1918, he was sent to France as a battalion medical officer. He saw heavy action in the last great battles of the war. His posting in France ended when he was wounded by shrapnel at Cambrai in September. Captain Banting recovered in England. He received the Military Cross for his valour under fire. In 1919, he returned to Canada.

General Practice

Frederick Banting took a year of surgical training at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. However, he could not obtain a staff position at a Toronto hospital. He decided to establish a general practice of medicine and surgery. He opened this practice in London, Ontario, in July 1920. Discouraged by its slow growth, he started working part-time at the University of Western Ontario. His job was to demonstrate principles of physiology to students.

Discovery of Insulin

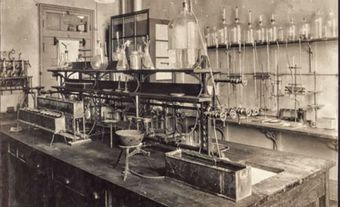

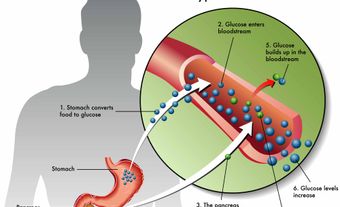

On the night of 31 October 1920, Frederick Banting wrote down an idea that set him on the path to the discovery of insulin. He had just read a routine article in a medical journal while preparing a talk to medical students. His idea concerned research to isolate an internal secretion of the pancreas that might prove to be a cure for diabetes. This substance had long been sought by other researchers. The next morning, he discussed the idea with F.R. Miller, a professor of physiology at Western. Miller advised him to seek support for his proposed research at the University of Toronto. On 17 May 1921, Banting began work under the direction of Professor J.J.R. Macleod and assisted by Charles Best.Banting and Best’s experiments in the summer and autumn of 1921 were crudely conducted. They did not prove Banting’s idea, which was physiologically unsound. Banting had left London and risked all of his meagre assets on the research in Toronto. However, he and Best did achieve favourable enough results treating some symptoms in diabetic dogs. Based on those results, Macleod approved further experimentation and an expansion of the research team.

A pitch of feverish, often contentious, activity followed. The stakes were high: success would mean saving human lives and becoming stars of science. The Toronto experiments culminated in the winter of 1921–22 in the discovery of insulin. The breakthrough was announced in Washington, DC, on 3 May 1922. By that time, the research team consisted of Banting, Best, Macleod, James B. Collip and three others.

Nobel Prize and Other Honours

Insulin was immediately and highly effective. While not a cure for diabetes mellitus, it was a powerful lifesaving therapy. Frederick Banting was hailed as the main discoverer of insulin. This is because his idea had launched the research, and he was a leader in the early use of insulin.

He and his supporters also campaigned to discredit his senior colleagues, Macleod and Collip. Banting thought the pair had tried to take over the project. Moreover, his temperament clashed with theirs. Macleod was a cautious, skeptical scientist. By contrast, Banting was a blunt, aggressive enthusiast. For years, misleading stories of heroic research by Banting and Best eclipsed Macleod and Collip’s key role in the discovery of insulin.

The 1923 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine recognized the contributions of both Banting and Macleod in this important breakthrough. On learning that he was to share the prize with Macleod, Banting gave half his prize money to Best. Macleod gave half his prize money to Collip. The Government of Canada awarded Banting regular payments for life. The University of Toronto appointed him Canada’s first professor of medical research. King George V knighted him in 1934. He was also made a Fellow of both the Royal Society (London) and the Royal Society of Canada. In 2021, Banting, Best, Macleod and Collip were inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame.

Did you know?

Frederick Banting remains the youngest winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He was 32 years old when he won the award.

Later Research

Frederick Banting became a popular hero and the most famous Canadian of the 1920s. He was widely expected to conquer more diseases. These expectations weighed heavily on the deeply insecure, poorly trained researcher. He was desperate to prove that his insulin adventure was no fluke.

In the 1920s, his partnership with Best having ended, Banting turned to cancer research. In this field he achieved nothing but frustration. He undertook strange ventures. For instance, he studied royal jelly (a substance secreted by honeybees) and tried to revive victims of drowning. These efforts went nowhere. Banting supervised a group of young scientists in his Department of Medical Research at the University of Toronto. Eventually, his team did do useful work on silicosis (an occupational lung disease) and other problems.

By the late 1930s Banting had become the effective head of Canada’s medical research effort. This role owed to his national prominence and enthusiasm for research. As the shadows of war again gathered, Banting became deeply interested in related medical issues. He effectively launched Canada’s first research efforts in aviation medicine and problems of chemical-bacterial warfare.

Banting was Canada’s chief liaison with British research scientists in the early days of the Second World War. In February 1941, he decided to make another trip to England. He arranged to hitch a ride on a Hudson bomber being ferried from Newfoundland to the United Kingdom.

After departing from Gander in bad weather, the plane developed engine trouble. It turned back and crashed by a pond in Newfoundland. Mortally injured, Major Sir Frederick Banting died before help reached the plane. There is no evidence to support stories that the plane had been sabotaged or that Banting’s mission was unusually important.

The Personality

Frederick Banting was shrewd, with an intense sense of integrity and duty. However, he had little training or experience as a scientist. He also did not deal well with the intense celebrity of his “discoverer of insulin” status. He had been almost broken by the pressures of the insulin research. Several times, he told friends that he was considering suicide if he failed. The stress also led to the end of the great romance of his life. Edith Roach, his childhood sweetheart, had been his on-again, off-again fiancée.

Inner harmony and outward grace both remained elusive for Banting. In 1924, he married the vivacious Marion Robertson. She was an x-ray technician who worked at the Toronto General Hospital. The couple soon discovered their marriage was a mistake. They had very different personalities and views about marriage. The couple had one child together, a son, William Robertson, who was born in April 1929. However, the marriage fell apart and they divorced in 1932, following allegations of adultery and abuse. Banting hated publicity, especially after the newspapers published details of his dramatic divorce.

In 1939, Banting married Henrietta “Henrie” Ball. She was a graduate science student at the University of Toronto who was working in his department. This brief second marriage ended with his death in 1941.

Some of Banting’s closest friends thought that he would have preferred a simpler life. They thought he would have been happier marrying his first love, Edith, and spending his life as a small-town doctor.

Amateur Painter

Frederick Banting did, though, find contentment in painting. As a member of Toronto’s Arts and Letters Club, he came to know most members of Canada’s Group of Seven school of landscape artists. He adopted their techniques and their intense sense of Canadian nationalism. He also adopted their genteel, bohemian approach to life. (This way of life included much male bonding and heavy drinking.) Banting and A.Y. Jackson of the Group went on several sketching trips together. Jackson’s influence was so strong that it is hard to tell some of their pieces apart. Banting often talked about his desire to retire and spend his time painting.

In recent years, Banting’s sketches and oils have regularly sold in the five-figure range. Like Banting’s medical career, the paintings reflect both natural ability and the artist’s good fortune in having been able to work with more talented associates.

Legacy

During and after his lifetime, Frederick Banting remained one of the world’s most famous Canadians. The very large international diabetes community expressed its gratitude for insulin with countless tributes to Banting. These include prizes, lectures, medals and other honours named after him. Canadian schools and a crater on the moon bear his name. He is always near the top of “most famous Canadian” polls. London, Ontario, is home to Banting House National Historic Site. This museum and attraction preserves the home where he conceived his great idea. The Banting homestead in Alliston, Ontario, is also a heritage site devoted to his work and life.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom