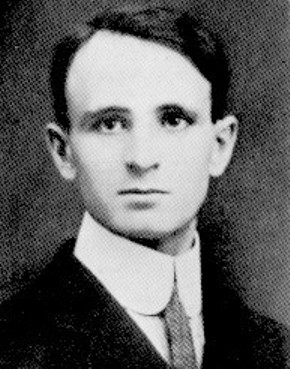

Early life

Olivar Asselin’s father, Rieule Asselin, a tanner by trade who greatly influenced his son’s liberal ideas, was mayor of the small community of Saint-Hilarion de Charlevoix before moving the family to Sainte-Flavie, Québec, where Asselin undertook his primary school education. Between 1886 and 1892 Asselin attended secondary school at the nearby Séminaire de Rimouski, where he excelled in commercial and classical studies as well as athletics. His naturally authoritative nature earned him the nickname “the little corporal.”

After the death of his mother, Adèle-Cédulie, and a fire at his father’s tannery, Olivar left school. His family joined hundreds of thousands of other French Canadians who, facing economic uncertainty, moved to the United States in the late 19th century to work in textile mills.

Living in America

The Asselin family arrived in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1892. Olivar worked in the local textile factories and briefly entertained ambitions to become a Jesuit. In 1894, he ventured into the world of journalism, first as a writer for Le Protecteur canadien and then as its editor-in-chief. Over the following six years, he moved around New England, taking on writing and editorial positions at several newspapers designed for a French Canadian readership. Struck by the rampant poverty in the industrialized region, he began working with and donating to the poor.

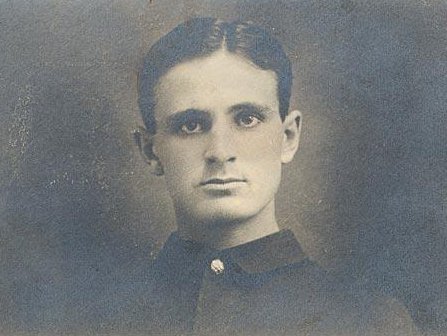

In 1898, Asselin became an American citizen, something he actively encouraged other French Canadian immigrants to do. He enlisted in the Spanish-American war but never saw combat. He did, however, achieve the rank of corporal.

Henri Bourassa and the Ligue nationaliste canadienne

By 1900, Asselin was back in Québec, living in Montréal and again working in the newspaper business. Shortly afterwards, he met Henri Bourassa, who had recently taken up a leadership role in the movement against Canada’s participation in the Boer War. A professional and personal friendship between the two men blossomed over the next few years, and Asselin became Bourassa’s right hand man as he grew increasingly committed to the nationalist cause.

Alongside Bourassa, Omer Heroux, Armand La Vergne and Jules Fournier, Asselin was one of the founding members of the Ligue nationaliste canadienne in 1903. He then co-founded and became editor of the Ligue’s newspaper, Le Nationaliste, in 1904. Asselin ran as a nationalist candidate in 1904 and 1911. Despite losing both times, he gained valuable political insight. For many years he organized speaking tours and published about 20 pamphlets — Feuilles de combat, or “fighting papers” as he called them — on questions of Canadian autonomy, provincial rights, education, imperialism, and every other major issue of the day.

Journalism and Politics

Asselin quit his position at Le Nationaliste in 1908 and became a correspondent for La Patrie in Ottawa and then Québec City. It was in the provincial capital where he famously slapped Minster of Public Works and Labour Louis-Alexandre Taschereau on the floor of the Legislative Assembly. Although briefly imprisoned, it did not stop him from continuing to engage in conflict with several leading figures and organizations in Québec and Canada, including Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Jean Prevost and Archbishop Bruchési.

After briefly writing for Bourassa’s Le Devoir in 1910, he wrote for Jules Fournier’s L’Action while working full-time as a real estate agent to support his wife, Alice Le Bouthillier — whom he had married on 3 August 1902 — and their four sons. In 1913–14, Asselin was president of the Société-Saint-Jean-Baptiste (SSJB), an important French-language patriotic association. Under his leadership, the SSJB campaigned against Regulation 17, a bill that restricted the rights of Franco-Ontarians from receiving an education in their language.

First World War

With the onset of the First World War, Asselin was sympathetic to the plight of France, which he considered to be “essential for the survival of the French Canadian civilization.” He became a recruitment officer, co-founding the 163rd Battalion (called les Poils-aux-pattes) in 1915 alongside Colonel Henri DesRosiers. After garrison duty in Bermuda, the unit was disbanded in England in early 1917. Asselin joined the French Canadian 22nd Infantry Battalion as a lieutenant and fought on the Western Front for the remainder of the war. He obtained an award for bravery at the Battle of Vimy Ridge. After suffering a bout of trench foot and clashing with Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay, Asselin moved to the 87th Battalion in 1918 where he helped liberate occupied Belgian and French villages. In 1919, he was bestowed the French Legion of Honour for his wartime service.

Journalism and Activism

Upon his return to Canada, Asselin busied himself in a wide array of activities. He was a literary critic for La Revue moderne, edited an anthology of the writings of his close friend Jules Fournier as well as Fournier’s Anthologie des poètes canadiens, and worked as a publicist for investment brokerage firms. He also wrote for L’Action française, the monthly magazine of the Ligue d’Action française, a nationalist organization led by the Abbé Lionel Groulx.

Asselin also became deeply involved in charitable work, devoting his time and money to several social welfare societies. He was an active member of the Saint-Vincent de Paul Society earlier in his life, and in 1925 he took over the Refuge Notre-Dame-de-la-Merci, a shelter for homeless, sick or troubled elderly men, for which he secured the services of the Frères Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean de Dieu. All the while, he kept up correspondence with friends and family at home and abroad and remained an engaged intellectual, writing essays on a variety of subjects. He did so while dealing with depression and periods of hospitalization.

Final Years

Asselin returned to full-time work in the newspaper business from 1930 to 1934, when he was editor for the Liberal newspaper Le Canada. Asselin revitalized the editorial team and successfully re-launched the paper, but left in 1934 to found his own newspaper with political leanings, L'Ordre, which featured a team of talented young journalists including Gérard Dagenais, Alfred DesRochers and Jean-Charles Harvey. However, the paper was forced to cease publication in 1935. That year, Asselin founded the short-lived newspaper La Renaissance. In 1936, Liberal premier Adélard Godbout named Asselin president of the Québec Old Age Pensions Commission. However, his health deteriorated soon thereafter and he was forced to resign. He died on 18 April 1937 at the age of 62.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom