Foundation and Early Years

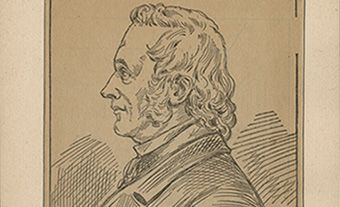

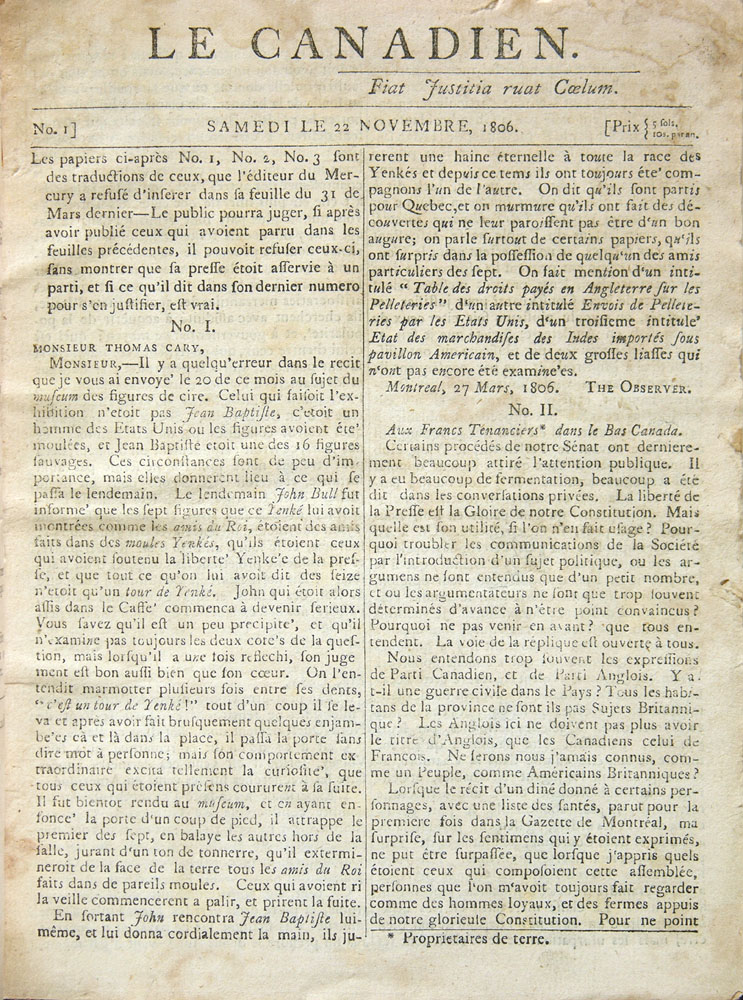

Le Canadien was founded in Québec City in 1806 by Pierre-Stanislas Bédard, François Blanchet, Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Joseph LeVasseur Borgia and Joseph Planté, all members — either then or soon afterwards — of the Parti canadien in the Legislative Assembly. It was created to defend and promote the political agenda of the Parti canadien, an alliance of Lower Canadian deputies — French and English — who sought to reform the government of Lower Canada. Formed about 1804, the Parti canadien was the first political party in Canadian history.

Created in order to counter the Quebec Mercury, the mouthpiece for the anti-reform British mercantile elite (or Château Clique), Le Canadien pressed for a government that was accountable to the elected assembly. It also battled the Château Clique’s assimilationist aims, and defended the interests of the French Canadian nation.

Le Canadien’s first run did not last long. Frustrated with the newspaper’s constant opposition, Governor James Craig (who shared the Château Clique’s views) arrested and imprisoned the editors of the paper in March 1810. The offices of Le Canadien were ransacked and its printing presses confiscated, forcing it to shut down temporarily.

Between 1810 and 1825, the newspaper had a difficult time finding its footing. In 1817, under the leadership of Laurent Bédard — the nephew of Pierre-Stanislas — the newspaper began printing again, only to stop in 1819. A year later, it began printing under the guidance of François Blanchet. Though this series only lasted until 1825, Blanchet made a decision that would change the course of the newspaper: in 1822, he gave Étienne Parent editorial duties. However, Parent’s first tenure as editor-in-chief was not very memorable, and the newspaper stopped printing three years later.

Étienne Parent Years: 1831–42

The newspaper returned in 1831. Under Parent’s guidance, it went from a weekly publication schedule to triweekly and continued to defend French Canadian interests. Parent declared in his first issue on 7 May 1831:

Our politics, our aims, our sentiments, our wishes and desires are to maintain all that constitutes our existence as a people, and, as a means to that end, to maintain all the civil and political rights that are the prerogative of an English country.

The newspaper also continued its close relationship with the party it was initially created to uphold, which was by then called the Parti patriote.

Unlike the party’s other mouthpiece — La Minerve, published in Montréal — Le Canadien was much more nuanced, moderate and pragmatic in its views, meaning it did not always toe the party line. From 1835 to the Rebellion of 1837, for instance, Parent constantly criticized the party’s growing radicalism and calls for violence. Though Parent shared the same goal as Louis-Joseph Papineau — namely, responsible government — he believed it should be achieved without the use of violence. As a result, he condemned Papineau for leading his followers to bloodshed. Parent was subsequently declared a “traitor” by newspapers La Minerve and the Vindicator as well as by the leaders of the Parti patriote.

Following the rebellions, Parent continued where he left off: approaching every event with the same pragmatism, while at the same time defending French Canadian interests. For instance, when Lord Durham landed in Canada, Parent applauded his arrival, hoping that the lauded liberal could restore peace and even possibly reform government. He even approached the initial plan to unite the Canadas with similar moderation, hoping that the restoration of representative government would be beneficial to French Canadians (see Act of Union). However, when it was obvious that Durham’s visit and the union of the Canadas would have dire consequences for the survival of French Canadians, he used Le Canadien to condemn both events and defend the interests of his people.

On 21 October 1842, after more than a decade at the helm of Le Canadien, Parent stepped down. Following the formation of the LaFontaine-Baldwin government, Parent accepted Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine’s invitation to act as the clerk of the Executive Council.

Post-Parent Years

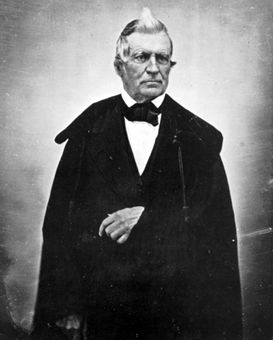

The newspaper’s editorial line continued to reflect the ideological position of its editors in the decades following Parent’s departure. The most famous post-Parent editor was Joseph-Israël Tarte, who joined the paper as assistant editor in 1874, later becoming editor-in-chief.

Under Tarte, the newspaper was initially a supporter of the federal Conservative Party. For example, the newspaper supported Hector-Louis Langevin’s federal campaign and relentlessly attacked the Liberals, calling them anticlerical. However, he later turned to Wilfrid Laurier and used Le Canadien to promote the Liberals as the defenders of French Canada.

In 1891, Tarte moved Le Canadien to Montréal, which was becoming known as “the epicentre of ideological, political and social movements.” However, the newspaper did not survive; Tarte closed it in 1893. The newspaper could not compete against newspapers that had a long history and were well-rooted in the city, such as the Montreal Star, Montreal Herald and La Patrie. According to historians Michèle Brassard and Jean Hamelin, Tarte also seemed to understand that the newspaper’s moment was over: “A newspaper of ideas, a fighting paper written for an intellectual and political elite, it was no longer suitable for the mass of urban readers, who looked for brief news items and sensationalism.” Tarte focused his energy on his other newspapers: Le Cultivateur and his column with L’Électeur.

In 1906, a conservative interest group tried to revive Le Canadien, but lacking funding, it closed three years later in 1909.

(See also Newspapers.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom