Overview

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic is a socialist state in Southeast Asia created on 2 December 1975. This territory was traditionally part of what Europeans called the “East Indies,” an important source of spices, silk and other trade goods beginning in the 16th century.

The French colonial era of Southeast Asia began with the French conquest of Saigon (today Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) in 1859, which contributed to the establishment of French Indochina. The area was attractive to France mainly because the Mekong River offered a gateway to China. In 1886, France signed a treaty with Siam (Thailand), of which Laos was then a vassal, in an attempt to facilitate commercial development. The following year, the French staked their claim to the kingdom of Siam based on its status as a tributary of Vietnam, which France already controlled. In 1893, Siam surrendered to France all territory east of the Mekong River, and all Laotian territories were brought together as a single administrative unit. France put little into the colonies. The colonial government was barely staffed and the royal court managed its own affairs while the territories were run by Vietnamese civil servants. In an effort to remove the Lao people from Siamese influence during the 1930s and 1940s, a small French-educated Lao elite promoted Lao language and literature, produced the first Lao history books and established Buddhist institutes.

The Second World War shattered French supremacy and strengthened nationalist sentiment in Laos. The Japanese occupied French Indochina in March 1945 and parts of Laos were given to Thailand. The Japanese forced King Sisavang Vong to declare independence from France but, in September 1945, following Japan’s surrender, the king moved to re-establish the French protectorate. Prime minister and hereditary viceroy Prince Phetsarath, leader of a resistance movement called Lao Issara (Free Laos), defied the king and declared a unified and independent Laos on 7 October. The king dismissed his prime minister, but a provisional government created a house of representatives that, on 20 October, removed the king from power and placed Phetsarath at the head of government. A prisoner in his own palace, the king renounced his throne on 10 November. Weeks later, in the winter of 1946, the French invaded Laos, recapturing cities controlled by the independence movement and returning the king to the throne as the constitutional monarch of Laos.

In April 1946, the French endorsed the unity of Laos as a constitutional monarchy within the French union. The revolutionary organization Viet Minh launched offensives against French rule in Vietnam, and the French government realized it would have to lighten its colonial burden to preserve its former empire. The Lao Issara, whose leaders had fled to Siam, were invited to attend formal negotiations for Laos’s greater autonomy. The leaders of the Lao Issara, unimpressed by French conditions for independence, established an alliance with the Viet Minh, which quickly gained a foothold in the northeastern provinces.

The French government granted full sovereignty to Laos and Cambodia in 1953 and withdrew. In May 1954, the French suffered a calamitous defeat at Ðiên Biên Phú, Vietnam, and sued for peace at the Geneva Conference of 1954, the conditions of which ended French involvement in Southeast Asia.

After gaining independence from France, Laos endured a civil war until 1975, when the communist faction took power. The country was also greatly affected by the Vietnam War. These upheavals, as well as poor economic conditions, led to the migration of many Laotians in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with Canada becoming one of the main resettlement countries for Laotian refugees (see Canadian Response to the "Boat People" Refugee Crisis).

Immigration History and Settlement in Canada

A small number of Laotian students had arrived in Canada in the 1950s and 1960s. Most of them came on scholarship through the Colombo Plan for Co-operative Economic Development in South and Southeast Asia, an initiative designed to promote stability in that region by improving the economies of its new states. The majority of these students studied in French at Québec universities and then settled in the province with their children. Some returned to their country of origin, but many chose to stay in Canada. Those who did soon found employment in a professional occupation, and three-quarters of them settled in the Montréal area. In 1974, there were approximately 200 Laotians living in Québec.

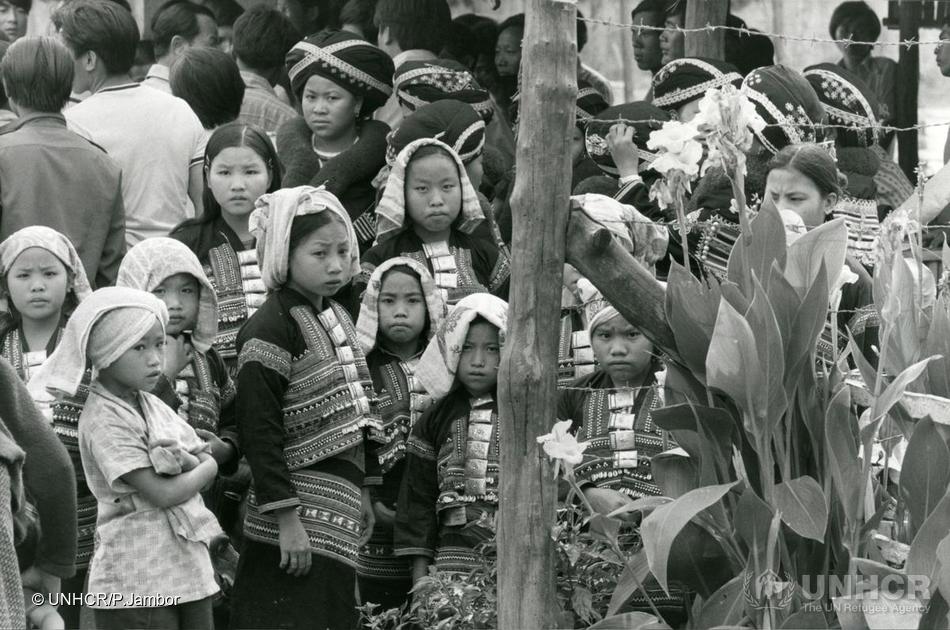

The majority of Laotian immigrants arrived in Canada after 1979. They came with the mass migration of people from mainland Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos), where an unprecedented humanitarian crisis was unfolding. Like many thousands of Vietnamese, Laotians fled their country in makeshift boats for camps run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Hong Kong. More than 50 per cent of these refugees came to Canada as a result of a brand-new private sponsorship program put in place by the government. From 1979 to 1982, Canada admitted 7,700 Laotians, of whom approximately 20 per cent were of Chinese origin.

After 1982, Canadian immigration policy promoted family reunification (see Immigration in Canada; Immigration Policy in Canada). More than half of the 1,500 Laotians who came to Canada between 1983 and 1986 applied as family members of individuals who had already settled in Canada. Immigration continued in the years that followed, but in the 1990s, the number of refugees and immigrants admitted into Canada from Laos dropped considerably. In total, Canada admitted nearly 13,000 Laotian refugees.

On 13 November 1986, in recognition of its exceptional contribution to refugee protection, Canada was awarded the Nansen Medal by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Governor General Jeanne Sauvé accepted the honour on behalf of the “People of Canada.” It is the only time the honour has been bestowed on an entire population.

Many of the new Laotian refugees after 1974 also settled in Québec (about 27 per cent of Laotian Canadians live in Montréal), while others moved to Ontario (to Kitchener, in particular) and elsewhere. Many of them had been educated in French, which made their transition easier, but some struggled with the language barrier and found themselves limited to work as labourers or in semi-skilled jobs. As well, the lack of larger, established Laotian communities in Canada added difficulties for the newcomers. In 2016, according to the Census of Canada, there were 24,590 people of Laotian origin in Canada (including both single and multiple ethnic-origin responses).

Social and Cultural Life

Looking to each other for support, Laotians in Canada developed their own religious and cultural organizations. Theravada Buddhism was an important common bond, and Laotian communities established several temples in Montréal, Toronto and Winnipeg that became central to religious, cultural and social events.

Several Laotian associations in Canada, the earliest established in the 1970s, have also formed women’s and youth groups, and sponsored cultural and recreational initiatives such as language classes, arts activities and a soccer league. Today, most Laotian Canadians still live in urban centres and maintain strong community connections.

Canada-Laos Relations

Canada and Laos have had diplomatic relations since 1954. The Canadian embassy in Bangkok has been accredited (certified to serve as an official representative) to Laos since 1974. Laos is represented in Canada by the Embassy of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic in Washington, DC. The two countries work together in the political and economic Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and are also partners in l’Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, whose goals include promoting peace, co-operation and sustainable development. The Canadian Francophonie Scholarship Program supports Laotian students who wish to study in French at a Canadian university.

Politically, Canada continues to encourage Laos to improve human rights and security, and has provided financial support for the clearing of unexploded landmines in the country. Canada also continues to encourage Laos to sign the Ottawa Treaty (Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction).

A version of this article appeared originally on Historica Canada’s Asia/Canada website

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom