The discovery of gold in the Yukon in 1896 led to a stampede to the Klondike region between 1897 and 1899. This led to the establishment of Dawson City (1896) and subsequently, the Yukon Territory (1898). The Klondike gold rush solidified the public’s image of the North as more than a barren wasteland and left a body of literature that has popularized and romanticized the Yukon.

History

The search for gold in the Yukon started in 1874 with the arrival of a small handful of prospectors. Among them were Arthur Harper, Al Mayo and Jack McQuesten (the former an Irish immigrant, the latter Americans). The three became traders because they couldn’t make a living as prospectors at that time. These men encouraged, promoted and then supplied the burgeoning prospecting community that developed slowly before the gold rush. At first a trickle, then a steadily increasing stream of hopeful prospectors entered the Yukon River basin, spurred on by the increasingly promising reports of gold on the bars of the Yukon and its tributaries: the Stewart River (1885), the Fortymile River (1886), the Sixtymile (1891) and finally Birch Creek, near Circle City, Alaska (1892). By 1896, there were 1,600 prospectors seeking gold within the Yukon River basin.

Gold was discovered in mid-August 1896 by George Carmack, an American prospector, Keish (aka Skookum Jim Mason) and Káa Goox (aka Dawson Charlie) — Tagish First Nation members into whose family Carmack had married. The discovery was made on Rabbit Creek, a small tributary of the Klondike River. It was soon renamed Bonanza Creek, a name that became world famous. When word of the discovery reached the outside world in July 1897, it sparked an unprecedented stampede. Tens of thousands of would-be prospectors left their homes all over the world, though mainly from the United States, and headed for the Klondike.

Joseph Ladue, an American who had been in the Yukon since 1882, operated a trading post on the Yukon River, 70 km above the mouth of the Klondike. While others staked claims for gold, Ladue was quick to capitalize on the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek. He staked out 65 hectares of swamp and moose pasture at the mouth of the Klondike River, called it Dawson City (after the famous Canadian geologist, George Mercer Dawson), and made a fortune selling lots and the lumber to build on them.

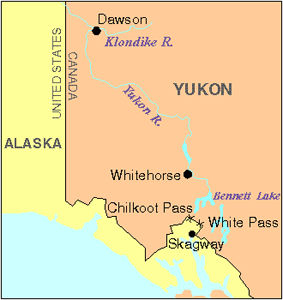

The stampede was an epic journey during which numerous challenges had to be met, and countless obstacles overcome. First, there was the harrowing voyage north along the Pacific coast from coastal cities such as Victoria, Seattle, Portland and San Francisco, which ended upon arrival at the coastal Alaskan ports of Haines, Skagway and Dyea. Haines was near the start of the Dalton Trail; Skagway, a lawless town run by the notorious Soapy Smith and his band of thieves, was the beginning of the White Pass Trail. Dyea was the starting point for the most famous gold rush trail of all: the Chilkoot.

There is no doubt that the Klondike Gold Rush was an iconic event. But what did the mining industry cost the original people of the territory? And what was left when all the gold was gone? And what is a sour toe cocktail?

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Images of a never-ending stream of men labouring up the icy steps of the final ascent to the Chilkoot Pass summit have come to symbolize the challenges not just of the trail to the Klondike, but of life itself. Thousands, burdened by heavy loads, made the ascent across the rocky summit 30 or 40 times in order to haul the tonne of supplies (enough to last a prospector for a year) that the North West Mounted Police required each stampeder to bring with him.

The stampeders laboured over a trail clogged with ice, snow and people; avalanche, drowning and disease; exhaustion, failure and heartbreak. Over the mountains and down the icy valleys along the Chilkoot and the White Pass Trails, they laboured until they reached the headwaters of the Yukon River. By the time the stampeders had relayed their tonne of supplies the 53 km over the Chilkoot Trail to Bennett, some had trekked as much as 4,000 km. At the boom town of Bennett, on the shores of Bennett Lake, the horde climbed aboard a hastily built fleet of rafts, scows and boats to float down 800 km of treacherous lakes and winding rivers, through canyons and rapids, to reach Dawson City.

At Dawson City, they found a bustling and rapidly growing city at the mouth of the Klondike River where scruffy Klondike millionaire veterans (a year’s residence in the Yukon entitled them to bear the name ‘Sourdough’) rubbed shoulders with newly arrived Cheechako (a Cheechako could only earn the title of sourdough after having survived an Arctic winter). It was a place where the mundane was surrounded by the larger-than-life episodes of a grand adventure. Upon arrival, many never even bothered to look for gold.

By the time the stampeders arrived in the Klondike to search for gold, it was too late to leave because the summers are short in the North. Each man (there were few women in Dawson at first) had to build shelter for the winter, and then endure seven months of cold, darkness, disease, isolation and monotony. For those lucky enough to find gold, nothing was beyond limits. Many successful prospectors lived extravagantly. For the majority, however, life was about survival and their existence was tedious.

Pay streaks meandered unpredictably through frozen gravel in the valley bottoms. Some miners became rich, while others found nothing. Newcomers were obliged to work along the margins of the creeks that were already staked. Some were fortunate to secure bench claims (on the hillsides above the creeks) which the sourdoughs deemed worthless. Many of these claims proved to be as rich as the creek claims below.

The population of the Klondike dwindled from the 25,000 or more during the hey-day of the gold rush, to a few hundred within a decade. A century later, however, gold mining is still the economic mainstay of the region.

Impact

If the nearly $29 million (figure unadjusted) in gold that was recovered during the heady years of 1897 to 1899 was divided equally among all of those who participated in the gold rush, the amount would fall far short of the total that they had invested, in time and money, to reach the Klondike. The continental economy, however, which had been locked in a depression and plagued by unemployment, benefited from the spending during the gold rush.

The Klondike gold rush brought about a rapid advance in the development of the Yukon Territory, which was officially formed by Parliament on 13 June 1898. The gold rush left an infrastructure of supply, support and governance that led to the continued development of the territory. Had it not been for the discovery of gold, development of this region would have been a slow and gradual process.

The gold rush brought tremendous upheaval and disenfranchisement for the people indigenous to the region. The Han people of the Yukon valley were pushed aside and marginalized. Only a century later, as a result of land claim settlements have the Tr’ondëk Hwech’in found redress and self-governance.

The most lasting legacy of the Klondike gold rush is the impression it left in the public mind. It was a shared experience which all participants faced, rich or poor, on a relatively similar footing, and which left its mark indelibly etched in their memories. Words like Klondike and Chilkoot evoke images of gold, adventure, challenge and the North. There is a Klondike ice cream bar and a Chilkoot automobile. Towns, streets and schools have been named after the Klondike as well. The adventures of the gold rush were also captured in popular literature in the writings of people such as Jack London, Robert Service and Pierre Berton. Their writing, and that of hundreds of others, has ensured that the Klondike gold rush will not be soon forgotten.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)