Context

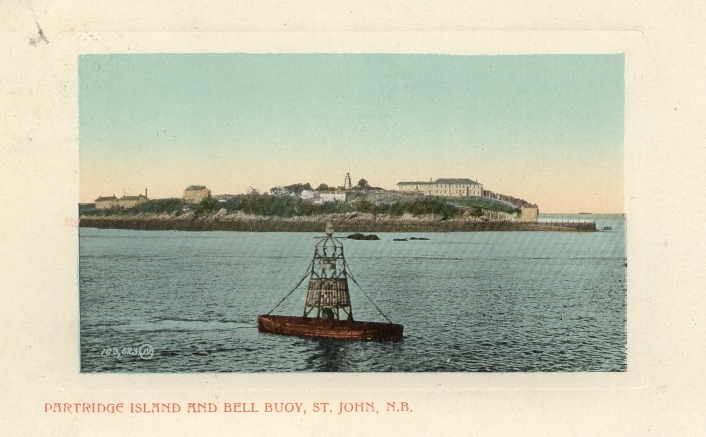

In the late 1840s, Ireland’s potato famine spurred the last major wave of Irish migration to what is now Canada. “Black ‘47,” the worst year, brought in approximately 110,000 migrants. Nearly 90,000 landed at the Grosse Île quarantine station before continuing to places including Québec City, Montréal, Canada West and the United States. The second major point of entry was the Partridge Island quarantine station outside Saint John, New Brunswick, which processed nearly 17,000 migrants. A small number also arrived in Halifax and other eastern ports.

Roughly one out of every six migrants to British North America in 1847 did not make it through the year. They died in the filthy holds of “coffin ships,” in crowded tents on the quarantine islands or in port cities. Most succumbed to the typhus epidemic raging at the time.

Children of the Famine

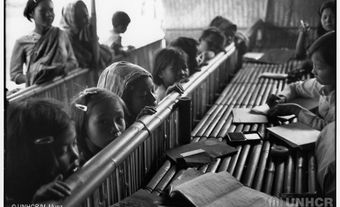

The number of child migrants who became orphans in 1847 was unprecedented. Grosse Île usually dealt with around 10 orphans per year, but there were over 100 less than a month into the 1847 navigation season. By year’s end, thousands of children had become orphans. The exact number is hard to determine given that many were informally placed out and left no trace in the records. Approximately nine out of every 10 orphans were Catholic.

At the time, the word “orphan” usually referred to children with nobody to look after them who were directly dependent on charity. It did not refer solely to children whose parents had died. In fact, many orphans had a living parent who was sick; who did not have enough money to care for them; who worked as a live-in domestic; who had abandoned them; who lived elsewhere in North America; or who had remained in Ireland. Some children migrated with older family members to join up with relatives already established in North America and became orphans when these caretakers died or abandoned them. Over a third of the famine orphans in Québec City had at least one parent that was still alive.

Welcoming Structures

Public authorities, religious officials and private charities all helped cope with the orphan crisis. Initially, the government worked to contain the epidemic, overseeing the quarantine stations and many of the hospitals that looked after sick migrants. Religious officials and private charities nursed the sick, administered sacraments and found homes for the children.

In most major cities, both public and private authorities built additional temporary “fever sheds” and orphanages to manage the emergency. Given the slow incubation time of typhus, many migrants carried the infection further inland. As a result, over 3,000 migrants died in Montréal fever sheds, over 1,000 in the Toronto sheds and roughly 700 in the temporary structures built in Kingston. In some cities, these shelters were staffed by nuns, as in Montréal where many Sisters of Providence and Grey Nuns lost their lives caring for migrants. Elsewhere, such as Québec City, the shelters were mostly looked after by laypersons.

Churches fronted many of the costs involved in caring for the orphans with money raised in Sunday collections and charity campaigns. In the latter third of 1847, the government stepped up its participation and reimbursed expenses for clothing, shelter, travel and medical help provided to the orphans. However, public authorities insisted that this aid was exceptional and non-recurrent, and that orphans should be rapidly placed out.

Finding Homes

Homes were quickly found for most orphans. For example, in Québec City, orphans only spent an average of one to two months under parish care or in institutions.

Many children ended up with parents or relatives. Around half the famine orphans in Saint John were sent to family members, the majority of whom lived in the United States.

For the rest, priests and ministers played a major role in placing out the orphans. They solicited their parishioners on Sundays, organized public processions of orphan children and spread the word to clergy in other parishes. Most orphans in Canada East were placed in families of their faith, though not necessarily their ethnicity; for instance, over half the orphans in Québec City were placed in Catholic Francophone families, many in the countryside. Conversely, the Emigrant Orphan Asylum in Saint John deliberately placed most Catholic children in Protestant families, thereby facilitating their conversion.

Placing Out

During these years, the adoption procedure in British North America was informal and non-binding. Although the word “adoption” was used at the time, it signified a reality that was more like foster care or apprenticeship. Formal adoption processes with legal guarantees of tutelage did not exist in Canada until the 1870s. Parents had no official rights over orphans placed in their care, and children had no legal claims on their “families” in later years. Census returns show that around two thirds of the orphans were not considered sons or daughters by their foster parents.

Despite this situation, the stories that have filtered down through generations suggest most orphans were properly treated by their host families. For instance, orphan Daniel Tighe was adopted by the Coulombe family of Lotbinière, eventually inherited the family farm, and passed on fond memories of his adoptive parents to descendants. Although some orphans were placed out two or three times, indicating an initial mismatch, over 75 per cent of the orphans who came through Québec City stayed with their original adoptive family.

Families had several reasons for taking in famine orphans. Many Irish families were motivated by ethnic solidarity. Others were prompted by Christian charity. However, most families were grateful for extra hands on the farm or in the household. This is why older children were typically favoured. Younger orphans were more likely to stay in institutions until they were old enough to earn their keep in a family setting.

Questioning the Legacy

In the decades after the famine, the story of the famine orphans became romanticized. Writers like John Maguire and Bernard O’Reilly transformed the story into a parable of conciliation between French-Canadians and Irish. Adoptive parents were usually depicted as self-sacrificing Francophones who consciously sought to preserve the orphans’ Irish Catholic heritage. This notion was reinforced throughout the 1990s by the “Orphans” Heritage Minute, which was broadcast regularly on CBC/Radio-Canada.

Since the last two decades, historians have challenged the mythmaking around the famine orphans. Jason King looked at the construction of this myth, and Marie-Claude Belley debunked it with figures and facts. Orphans were usually taken in for pragmatic reasons. They kept their Irish surnames because they were not formally adopted but informally placed out. This revisionism has blunted the romantic edge to the famine orphan narrative, but some stories still show that conciliation across ethno-religious lines did take place.

See also Irish Potato Famine Refugees.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom