The First World War of 1914–1918 was the bloodiest conflict in Canadian history, taking the lives of nearly 61,000 Canadians. It erased romantic notions of war, introducing slaughter on a massive scale, and instilled a fear of foreign military involvement that would last until the Second World War. The great achievements of Canadian soldiers on battlefields such as Ypres, Vimy and Passchendaele, however, ignited a sense of national pride and a confidence that Canada could stand on its own, apart from the British Empire, on the world stage. The war also deepened the divide between French and English Canada and marked the beginning of widespread state intervention in society and the economy.

(This is the full-length entry about the First World War. For a plain-language summary, please see First World War (Plain-Language Summary).)

Going to War

The Canadian Parliament didn't choose to go to war in 1914. The country's foreign affairs were guided in London. So when Britain's ultimatum to Germany to withdraw its army from Belgium expired on 4 August 1914, the British Empire, including Canada, was at war, allied with Serbia, Russia, and France against the German and Austro-Hungarian empires.

The war united Canadians at first. The Liberal opposition urged Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative government to take sweeping powers under the new War Measures Act. Minister of Militia Sam Hughes summoned 25,000 volunteers to train at a new camp at Valcartier near Québec; some 33,000 appeared. On 3 October, the First Contingent of 30,617 men sailed for England. Much of Canada's war effort was launched by volunteers. The Canadian Patriotic Fund collected money to support soldiers' families. A Military Hospitals Commission cared for the sick and wounded. Churches, charities, women's organizations, and the Red Cross found ways to "do their bit" for the war effort. (See Wartime Home Front and Canadian Children and the Great War.) In patriotic fervour, Canadians demanded that Germans and Austrians be dismissed from their jobs and interned ( see Internment), and pressured Berlin, Ontario, to rename itself Kitchener.

War and the Economy

At first the war hurt a troubled economy, increasing unemployment and making it hard for Canada's new, debt-ridden transcontinental railways, the Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific, to find credit. By 1915, however, military spending equaled the entire government expenditure of 1913. Minister of Finance Thomas White opposed raising taxes. Since Britain could not afford to lend to Canada, White turned to the US.

Also, despite the belief that Canadians would never lend to their own government, White had to take the risk. In 1915 he asked for $50 million; he got $100 million. In 1917 the government's Victory Loan campaign began raising huge sums from ordinary citizens for the first time. Canada's war effort was financed mainly by borrowing. Between 1913 and 1918, the national debt rose from $463 million to $2.46 billion, an enormous sum at that time.

Canada's economic burden would have been unbearable without huge exports of wheat, timber and munitions. A prewar crop failure had been a warning to prairie farmers of future droughts, but a bumper crop in 1915 and soaring prices banished caution. Since many farm labourers had joined the Army, farmers began to complain of a labour shortage. It was hoped that factories shut down by the recession would profit from the war. Manufacturers formed a Shell Committee, got contracts to make British artillery ammunition, and created a new industry. It was not easy. By summer 1915, the committee had orders worth $170 million but had delivered only $5.5 million in shells. The British government insisted on reorganization. The resulting Imperial Munitions Board was a British agency in Canada, though headed by a talented, hard-driving Canadian, Joseph Flavelle. By 1917, Flavelle had made the IMB Canada's biggest business, with 250,000 workers. When the British stopped buying in Canada in 1917, Flavelle negotiated huge new contracts with the Americans.

Recruitment at Home

Unemployed workers flocked to enlist in 1914–15. Recruiting, handled by prewar militia regiments and by civic organizations, cost the government nothing. By the end of 1914 the target for the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was 50,000; by summer 1915 it was 150,000. During a visit to England that summer, Prime Minister Borden was shocked with the magnitude of the struggle. To demonstrate Canadian commitment to the war effort, Borden used his 1916 New Year's message to pledge 500,000 soldiers from a Canadian population of barely 8 million. By then, volunteering had virtually run dry. Early contingents had been filled by recent British immigrants; enlistments in 1915 had taken most of the Canadian-born who were willing to go. The total, 330,000, was impressive but insufficient.

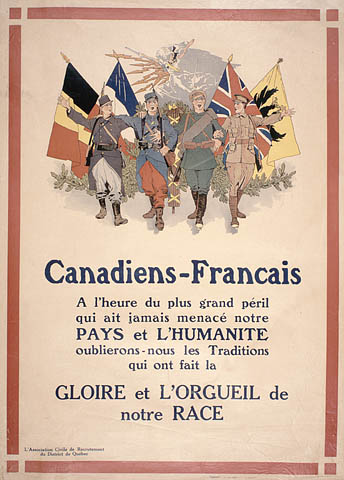

Recruiting methods became fervid and divisive. Clergy preached Christian duty; women wore badges proclaiming "Knit or Fight"; more and more English Canadians complained that French Canada was not doing its share. This was not surprising: few French Canadians felt deep loyalty to France or Britain. Those few in Borden's government had won election in 1911 by opposing imperialism. Henri Bourassa, leader and spokesman of Québec's nationalists, initially approved of the war but soon insisted that French Canada's real enemies were not Germans but "English-Canadian anglicisers, the Ontario intriguers, or Irish priests" who were busy ending French-language education in English-speaking provinces like Ontario (see The Battle of the Hatpins). In Québec and across Canada, unemployment gave way to high wages and a manpower shortage. There were good economic reasons to stay home.

Did You Know?

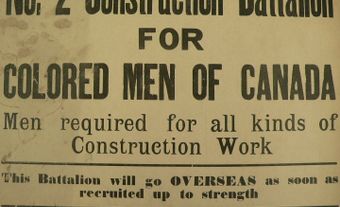

More than 4000 Indigenous men volunteered for overseas service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in the First World War. Modern historians and other researchers have show that a few thousand more Indigenous soldiers volunteered without self-identifying as Indigenous on their recruitment forms. Historian Timothy Winegard has revealed that recruitment and volunteerism of Indigenous soldiers breaks down into three phases. In the first phase, from August 1914 to December 1915, the Army “unofficially” accepted Indigenous soldiers, particularly Status Indians (First Nations men with legal Indian status). In other words, they allowed them to enlist but did not actively recruit them. In the second phase, from December 1915 to December 1916, the Canadian government and the Department of Indian Affairs relaxed restrictions against Indigenous volunteers as casualties grew for the CEF after deadly battles like the Second Battle of Ypres (1915) and the Battle of the Somme (1916). The third phase took place from 1917 to the end of the war. In the third phase, Indigenous volunteers were officially encouraged as voluntary enlistment dried up across Canada and Prime Minister Robert Borden decided to institute conscription (mandatory military service). The Military Service Act (MSA) of August 1917, which declared conscription of men aged 20-45, initially included all Indigenous men (except for Inuit men), regardless of their legal Indian status. Although First Nations and other Indigenous men were exempted from the MSA in January 1918, many more continued to volunteer through the end of the war. It is estimated that more than 1200 Indigenous soldiers were killed or wounded in the First World War (see Indigenous Peoples and the World Wars and Indigenous Peoples and the First World War).

The Canadian Expeditionary Force

Canadians in the CEF became part of the British army. As minister of militia, Sam Hughes insisted on choosing the officers and on retaining the Canadian-made Ross rifle. Since the rifle jammed easily and since some of Hughes' choices were incompetent cronies, the Canadian military had serious deficiencies. A recruiting system based on forming hundreds of new battalions meant that most of them arrived in England only to be broken up, leaving a large residue of unhappy senior officers. Hughes believed that Canadian civilians (rather than professional soldiers) would make natural soldiers; in practice they had many costly lessons to learn. They did so with courage and self-sacrifice.

At the second Battle of Ypres, April 1915, a raw 1st Canadian Division suffered 6,036 casualties, and the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry a further 678. The troops also shed their defective Ross rifles. At the St. Eloi craters in 1916, the 2nd Division suffered a painful setback because its senior commanders failed to locate their men. In June, the 3rd Division was shattered at Mount Sorrel though the position was recovered by the now battle-hardened 1st Division. The test of battle eliminated inept officers and showed survivors that careful staff work, preparation, and discipline were vital.

Canadians were spared the early battles of the Somme in the summer of 1916, though a separate Newfoundland force, 1st Newfoundland Regiment, was annihilated at Beaumont Hamel on the disastrous first day, 1 July. When Canadians entered the battle on 30 August, their experience helped toward limited gains, though at high cost. By the end of the battle the Canadian Corps had reached its full strength of four divisions. (See Battle of Courcelette.)

The embarrassing confusion of Canadian administration in England, and Hughes's reluctance to displace his cronies, forced Borden's government to establish a separate Ministry of Overseas Military Forces based in London to control the CEF overseas. Bereft of much power, Hughes resigned in November 1916. The Act creating the new ministry established that the CEF was now a Canadian military organization, though its day-to-day relations with the British Army did not change immediately. Two ministers, Sir George Perley and then Sir Edward Kemp, gradually reformed overseas administration and expanded effective Canadian control over the CEF.

(See also: The Canadian Great War Soldier and Canadian Command During the Great War.)

Other Canadian Efforts

While most Canadians served with the Canadian Corps or with a separate Canadian cavalry brigade on the Western Front, Canadians could be found almost everywhere in the Allied war effort. Young Canadians had trained (initially at their own expense) to become pilots in the British flying services. In 1917 the Royal Flying Corps opened schools in Canada, and by war's end almost a quarter of the pilots in the Royal Air Force were Canadians. Three of them, Major William A. Bishop, Major Raymond Collishaw, and Colonel William Barker, ranked among the top air aces of the war. An independent Canadian air force was authorized in the last months of the war (see The Great War in the Air.)

Canadians also served with the Royal Navy, and Canada's own tiny naval service organized a coastal submarine patrol.

Thousands of Canadians cut down forests in Scotland and France and built and operated most of the railways behind the British front. Others ran steamers on the Tigris River, cared for the wounded at Salonika (Thessaloniki), Greece, and fought Bolsheviks at Archangel and Baku (see Canadian Intervention in Russian Civil War).

Vimy and Passchendaele

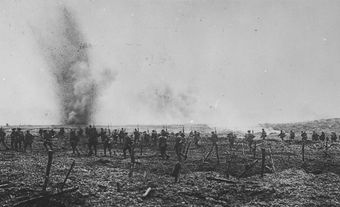

British and French strategists deplored diversions from the main effort against the bulk of the German forces on the European Western Front. It was there, they said, that war must be waged. A battle-hardened Canadian Corps was a major instrument in this war of attrition (see Canadian Command during the Great War). Its skill and training were tested on Easter weekend, 1917, when all four divisions were sent forward to capture a seemingly impregnable Vimy Ridge. Weeks of rehearsals, stockpiling, and bombardment paid off. In five days, the ridge was taken.

The able British commander of the corps, Lt-Gen Sir Julian Byng, was promoted; his successor was a Canadian, Lt-Gen Sir Arthur Currie, who followed Byng's methods and improved on them. Instead of attacking Lens in the summer of 1917, Currie captured the nearby Hill 70 and used artillery to destroy wave after wave of German counterattacks. As an increasingly independent subordinate, Currie questioned orders, but he could not refuse them. When ordered to finish the disastrous British offensive at Passchendaele in October 1917, Currie warned that it would cost 16,000 of his 120,000 men. Though he insisted on time to prepare, the Canadian victory on the dismal and water-logged battlefield left a toll of 15,654 dead and wounded.

(See also: Evolution of Canada's Shock Troops)

Borden and Conscription

By 1916, even the patriotic leagues had confessed the failure of voluntary recruiting. Business leaders, Protestants, and English-speaking Catholics such as Bishop Michael Fallon grew critical of French Canada. Faced with a growing demand for conscription, the Borden government compromised in August 1916 with a program of national registration. A prominent Montréal manufacturer, Arthur Mignault, was put in charge of Québec recruiting and, for the first time, public funds were provided. A final attempt to raise a French Canadian battalion —the 14th for Quebec and the 258th overall for Canada — utterly failed in 1917.

Until 1917, Borden had no more news of the war or Allied strategy than he read in newspapers. He was concerned about British war leadership but he devoted 1916 to improving Canadian military administration and munitions production. In December 1916, David Lloyd George became head of a new British coalition government pledged wholeheartedly to winning the war. An expatriate Canadian, Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, helped engineer the change. Faced by suspicious officials and a failing war effort, Lloyd George summoned leaders of the Dominions to London. They would see for themselves that the Allies needed more men. On 2 March, when Borden and his fellow premiers met, Russia was collapsing, the French army was close to mutiny, and German submarines had almost cut off supplies to Britain.

Borden was a leader in establishing a voice for the Dominions in policy making and in gaining a more independent status for them in the postwar world. Visits to Canadian camps and hospitals also persuaded him that the CEF needed more men. The triumph of Vimy Ridge during his visit gave all Canadians pride but it cost 10,602 casualties, 3,598 of them fatal. Borden returned to Canada committed to conscription. On 18 May 1917 he told Canadians of his government's new policy. The 1914 promise of an all-volunteer contingent had been superseded by events.

Many in English-speaking Canada — farmers, trade union leaders, pacifists, and Indigenous leaders — opposed conscription, but they had few outlets for their views. French Canada's opposition was almost unanimous under Henri Bourassa, who argued that Canada had done enough, that Canada's interests were not served by the European conflict, and that men were more needed to grow food and make munitions.

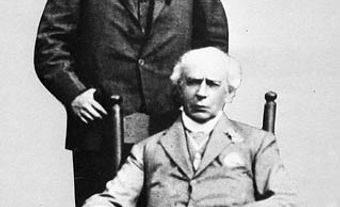

Borden felt such arguments were cold and materialistic. Canada owed its support to its young soldiers. The Allied struggle against Prussian militarism was a crusade for freedom. There was no bridging the rival points of view. To win conscription, Borden offered Sir Wilfrid Laurier a coalition. The Liberal leader refused, sure that his party could now defeat the Conservatives. He also feared that if he joined Borden, Bourassa's nationalism would sweep Québec. Laurier misjudged his support.

Many English-speaking Liberals agreed that the war was a crusade. A mood of reform and sacrifice had led many provinces to grant votes to women and to prohibit the sale or use of liquor (see Temperance Movement in Canada). Although they disliked the Conservatives, many reform Liberals like Ontario's Newton Rowell believed that Borden was in earnest about the war and Laurier was not. Borden also gave himself two political weapons: on 20 September 1917 Parliament gave the franchise to all soldiers, including those overseas; it also gave votes to soldiers' wives, mothers and sisters, as well as to women serving in the armed forces, and took it away from Canadians of enemy origin who had become citizens since 1902 (see Wartime Elections Act). This added many votes for conscription and removed certain Liberal voters from the lists. On 6 October, Parliament was dissolved. Five days later, Borden announced a coalition Union government pledged to conscription, an end to political patronage, and full Women's Suffrage.

Eight of Canada's nine provinces endorsed the new government, but Laurier could dominate Québec, and many Liberals across Canada would not forget their allegiance. Borden and his ministers had to promise many exemptions to make conscription acceptable. On 17 December, Unionists won 153 seats to Laurier's 82, but without the soldiers' vote, only 100,000 votes separated the parties (see Election of 1917). Conscription was not applied until 1 January 1918. The Military Service Act had so many opportunities for exemption and appeal, that of more than 400,000 called, 380,510 appealed. The manpower problem continued.

Although conscription was controversial, dividing English and French Canada, 24,132 conscripted soldiers (“MSA men”) reached the Western Front in time to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force for the huge battles of 1918. This was vital during the final hundred days of war between August and November 1918 (see Canada’s Hundred Days). With 48 infantry battalions of roughly 1000 men each, the Canadian Corps was greatly boosted by the 24,000-plus conscripts in the last months of the war—the “MSA men” represented a boost of about 500 men per battalion for the CEF in the final stage of the war.

Take the quiz!

Test your knowledge of the First World War by taking this quiz, offered by the Citizenship Challenge! A program of Historica Canada, the Citizenship Challenge invites Canadians to test their national knowledge by taking a mock citizenship exam, as well as other themed quizzes.

The Final Phase

In March 1918, disaster fell upon the Allies. German armies, moved from the Eastern to the Western Front after Russia's collapse in 1917, smashed through British lines. The Fifth British Army was destroyed. In Canada, anti-conscription riots in Québec on Easter weekend left four dead. Borden's new government cancelled all exemptions. Many who had voted Unionist in the belief that their sons would be exempted felt betrayed.

The war had entered a bitter final phase. On 6 December 1917 the Halifax Explosion killed over 1,600, and it was followed by the worst snowstorm in years. Across Canada, the heavy borrowing of Sir Thomas White (federal minister of finance) finally led to runaway inflation. Workers joined unions and struck for higher wages. Food and fuel controllers now preached conservation, sought increased production and sent agents to prosecute hoarders. Public pressure to "conscript wealth" forced a reluctant White in April 1917 to impose a Business Profits Tax and a War Income Tax (see Taxation in Canada). An "anti-loafing" law threatened jail for any man not gainfully employed. Federal police forces were ordered to hunt for sedition. Socialist parties and radical unions were banned. So were newspapers published in the "enemy" languages. Canadians learned to live with unprecedented government controls and involvement in their daily lives. Food and fuel shortages led to "Meatless Fridays" and "Fuelless Sundays."

In other warring countries, exhaustion and despair went far deeper. Defeat now faced the western Allies, but the Canadian Corps escaped the succession of German offensives. Sir Arthur Currie insisted that it be kept together. A 5th Canadian division, held in England since 1916, was finally broken up to provide reinforcements.

The United States entered the war in the spring of 1917, sending reinforcements and supplies that would eventually turn the tide against Germany. To help restore the Allied line, Canadians and Australians attacked near Amiens on 8 August 1918 (see Battle of Amiens). Shock tactics — using airplanes, tanks, and infantry — shattered the German line. In September and early October the Canadians attacked again and again, suffering heavy casualties but making advances thought unimaginable (see Battle of Cambrai). The Germans fought with skill and courage all the way to Mons, the little Belgian town where fighting ended for the Canadians at 11 a.m. (Greenwich time), 11 November 1918. More officially, the war ended with the Treaty of Versailles, signed 28 June 1919.

Canada alone lost 61,000 war dead. Many more returned from the conflict mutilated in mind or body. More than 170,000 were seriously wounded in battle, and thousands more suffered from “shell-shock” (see Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Canada). The survivors found that almost every facet of Canadian life, from the length of skirts to the value of money, had been transformed by the war years. Governments had assumed responsibilities they would never abandon. The income tax would survive the war. So would government departments later to become the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Pensions and National Health.

Overseas, Canada's soldiers had struggled to achieve, and had won, a considerable degree of autonomy from British control. Canada's direct reward for her sacrifices was a modest presence at the Paris Peace Conference at Versailles (see Treaty of Versailles) and a seat in the new League of Nations. However, the deep national divisions between French and English created by the war, and especially by the conscription crisis of 1917, made postwar Canada fearful of international responsibilities. Canadians had done great things in the war but they had not done them together.

(See also: Art and the Great War, Documenting Canada's Great War, In Flanders Fields, Monuments of the First and Second World Wars and Unknown Soldier.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

![Sir Robert Borden reviewing Canadians at Bramshott, [England] April, 1917.](https://d3d0lqu00lnqvz.cloudfront.net/media/vimy_foundation/VF1-2/VF1-14.jpg)