“The first real bookseller in Lower Canada”

Born on 15 September 1799, Édouard-Raymond Fabre’s childhood remains elusive to historians. It is known, however, that he grew up in Montréal and that he had a modest upbringing, as his father was a carpenter. Between 1807 and 1812, Fabre attended the Petit Séminaire de Montréal. At 14, he started working for one of Montréal’s most successful businesses: Arthur Webster’s hardware store. In 1822, Fabre left Montréal for Paris, where he worked for the renowned Galeries Bossange. There, he learned the skills it took to become a successful bookseller. A year later, he returned to Montréal and put these skills to use. According to historian Jean-Louis Roy, Fabre was “the first real bookseller in Lower Canada.”

In 1823, Fabre purchased, from Théophile Dufort, the bookstore that had formerly belonged to Bossange in Montréal. Fabre’s bookstore was known, between 1823 and 1828, as the Librairie française or Librarie Édouard-Raymond Fabre. This was more than a bookstore; it became a meeting place for the Patriotes. In 1828, he became a partner in business with his brother-in-law Louis Perrault, an important Patriotein his own right. This partnership ended in 1835. In 1844, he partnered with his nephew Jean-Adolphe Gravel, a business relationship that continued until Fabre’s death in 1854.

Fabre’s bookstore attracted a wide variety of customers, including lawyers, doctors, teachers, students and religious figures. According to Roy, Fabre carried a diverse but modest selection of books on various subjects, including history, law and politics — though in later years his stock focused mostly on religious works and textbooks — as well as supplies such as envelopes, pens, maps and religious items. Fabre’s bookstore was also the depository for official Legislative Assembly and Imperial Parliament documents relating to the colony.

Patriote

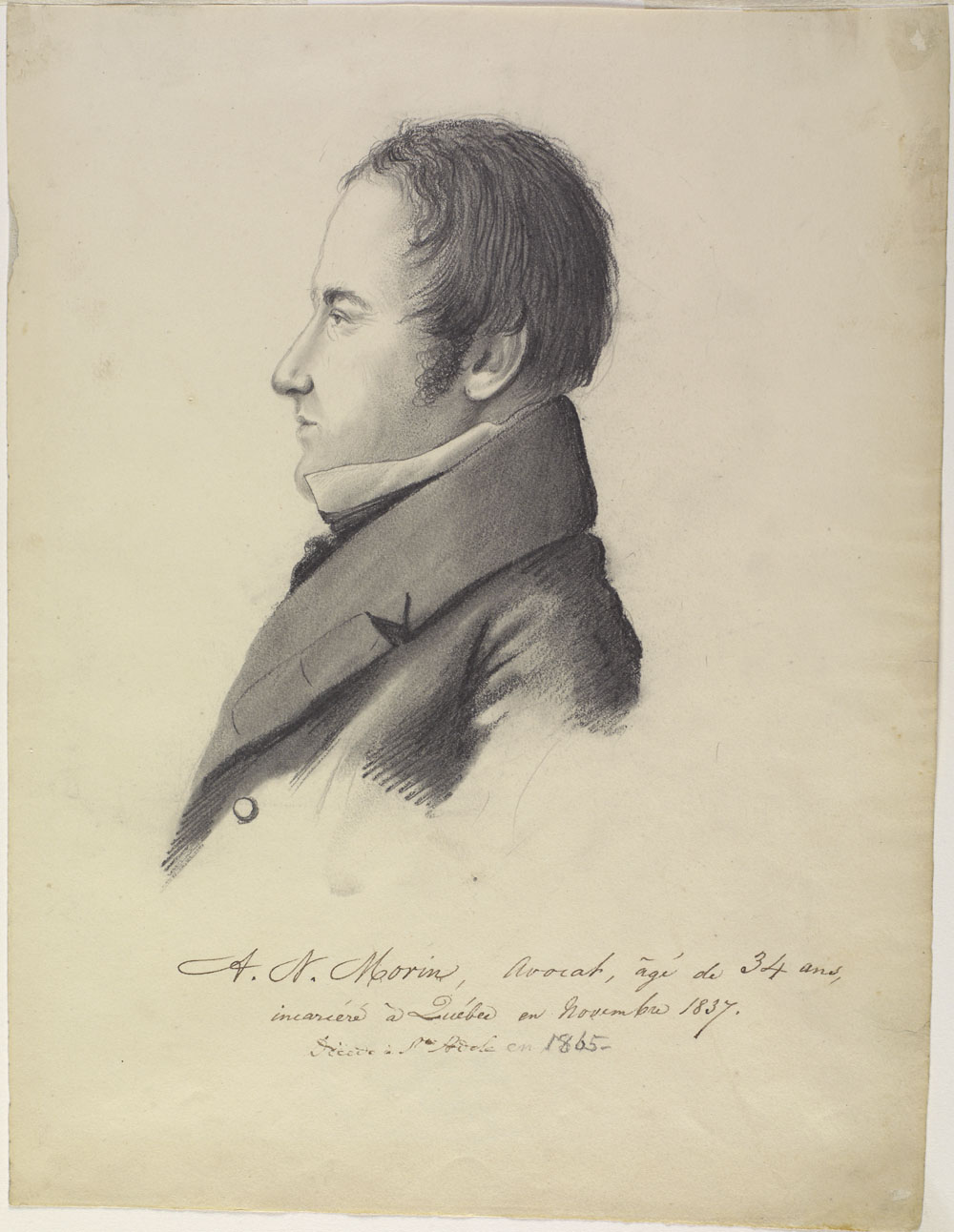

Édouard-Raymond Fabre was also a Patriote, and though he did not hold a seat at the Legislative Assembly, he played an important role in the movement. For instance, in 1832, he helped found the Maison canadienne de commerce, aimed at supporting French Canadian businesses. In 1834, he played a major role in the creation of La Banque du peuple, acting as its treasurer when it officially opened in 1835. That year, along with other high profile Patriotes, such as Augustin-Norbert Morin Denis-Benjamin Viger, and Edmund Baily O’Callaghan, he established the Union patriotique in Montréal, which, according to Le Canadien, acted as a source “of resistance against abuses of power.”

Fabre also used his financial success to help his Patriotefriends and allies. For instance, he financed Ludger Duvernay’s La Minerve and purchased the Vindicator and Canadian Advertiser, ensuring that both Patriotemouthpieces continued to circulate. He even organized a fundraiser to aid Durvernay after a period of imprisonment.

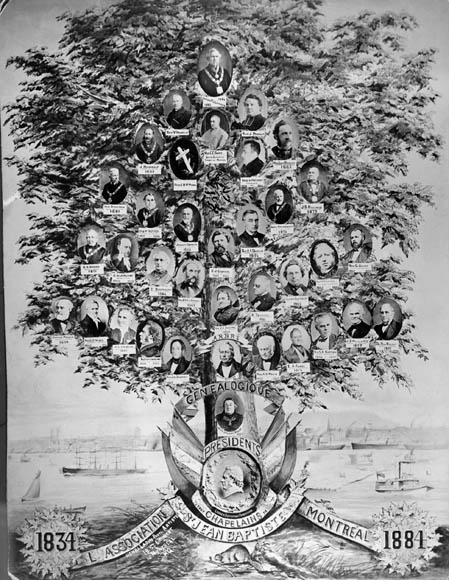

Though perhaps not as famous as other Patriotes, such as Viger, O’Callaghan, Duvernay or Louis-Joseph Papineau, Fabre left his mark on the movement. His bookstore acted as the meeting place for the city’s Patriotes, and by 1836 it also served as the meeting place for the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Fabre was also an adviser to Papineau and played an active role in the 1837 summer protests and meetings. During the rebellion, Fabre joined Papineau and O’Callaghan at Saint-Denis and convinced them to escape to the United States. Fabre did not follow. Instead, he lay low at Contrecoeur or thereabouts. He was arrested in December 1838 but was released shortly after due to the absence of evidence.

Post-Rebellion

Following the rebellion, Édouard-Raymond Fabre continued to assist his Patriotefriends and allies. In 1842, he helped Durvernay reorganize La Minerve. Fabre also played a substantial role in bringing back the political exiles to Lower Canada. As the treasurer of the Association de la déliverance, he raised over £2,300 to finance their return. Fabre also organized and sent petitions to London in their favour. In 1844, the British Colonial Office approved the return of the political exiles, and in 1846 the last ones arrived in Canada East.

Fabre longed for Louis-Joseph Papineau’s return to politics and Canada, even visiting him in Paris in 1843, where they discussed the former leader’s eventual return. Politically, the colony was once again divided, this time between supporters of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine’s Reformers and the more radical Denis-Benjamin Viger. To Fabre, only the return of Papineau could end this division. He expected that Papineau’s mere presence in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada would be enough to re-establish his leadership and end this division. However, when Papineau returned to the Assembly in 1848, hope soon turned to disappointment. The former leader was too divisive; his radicalism found itself at odds with La Fontaine’s Reformers and Duvernay’s La Minerve.

During this time, Fabre was a supporter of the Parti rouge, though he was one of its more moderate elements. Fabre initially backed L’Avenir — the radical voice of the party — but he ended his relationship with the newspaper and in 1852 founded Le Pays with Jacques-Alexis Plinguet. Though the newspaper similarly favoured electoral reform and the end of union of Canada East and Canada West, it avoided all criticisms of the Church. To Jean-Louis Roy, L’Avenir’s blatant attacks against the Church likely ended Fabre’s support; the Church, an important patron of his bookstore, was one of the sources of his financial success.

Mayor of Montreal

In the final years of his life, Édouard-Raymond Fabre enjoyed a successful career in municipal politics, though he remained lukewarm about it throughout. For years, he had snubbed pleas from the residents of his neighbourhood who “absolutely” wished to send him to city council. In 1848, he finally gave in and ran for council, winning in the East Ward of Montréal. Fabre was then appointed alderman and president of the finance committee. Montréal was a fiscal mess, with the city consistently running a deficit, and in his duties as president Fabre reduced the city’s debt for the first time since its second incorporation in 1840.

In 1849, without seeking it, he was named mayor of Montréal, most likely the result of his successes on the finance committee. During his first mandate, he handled two difficult situations: the 1849 Montreal Riots, caused by the Rebellion Losses Bill, and the cholera epidemic. Fabre did not enjoy his time as mayor; he felt isolated and feared for the safety of the city following the riots. Nonetheless, he continued to clean up the city’s finances and reduce spending.

In 1850, once again without seeking it, he was named mayor. He even told his sister that he did everything he could to not return as mayor, but his colleagues re-elected him anyway. Fabre created a full-time team of firefighters and extended the city’s aqueduct system. In February 1851, he thanked city council, finally ending his tenure as mayor. In 1854, following an unsuccessful campaign against Wolfred Nelson for mayor of Montréal, Fabre died, a victim of cholera.

Fabre left his mark on Canadian history, but so did his children. Édouard-Charles, for instance, was the very first archbishop for the city of Montréal, and Hector was Canada’s first diplomat in Paris as well as an important journalist, writing for some of the colony’s most-read newspapers, such as Le Canadien. His daughter Hortense married George-Étienne Cartier, making the Édouard-Raymond the father-in-law of a Father of Confederation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom