Economics involves the study of 3 interrelated issues: the allocation of resources used for the satisfaction of human wants; the income distribution among individuals and groups; and the determination of the level of national output and employment. Economists investigate these issues either from the perspective of microeconomics, an analysis of the behaviour of the individual units in the national economy, including business firms, workers and consumers; or from the perspective of macroeconomics, the study of the larger aggregates in the economy, such as total investment and consumption, the average levels of interest rates and price indexes, and total employment and unemployment.

Economic Research

Economic research consists primarily of the formulation of theories that seek to explain observable events (such as variations in Canadian exports of pulp and paper or Canadian purchases of computers) and the testing of theories by comparing their implications or predictions with actual events. Theories and tests may be formal and mathematical, or informal and based on nonmathematical discourse. The formulation and testing of both kinds of theories in Canada has been greatly aided by the growth of a reliable body of national statistical data on economic phenomena which followed the founding of the Dominion Bureau of Statistics in 1918.

The trend of economic research over the past 50 years has been toward reliance on increasingly sophisticated mathematical models and formal statistical tests, to the despair of some critics in the profession who argue that the discipline tends to ignore or distort human behaviour and institutional complexity, which are not easily amenable to such analysis.

Mathematical Models

Mathematical models often focus on the concept of equilibrium, a situation in which producers and consumers of a good are assumed to be maximizing their incomes and utility subject to their initial wealth and to market prices, and have in the course of their trading found a consistent or equilibrium price that maintains the outputs and purchases of all parties. The models allow comparisons of equilibrium positions after a change in a particular parameter; for example, with a formal mathematical model of production in the plastics industry, the impact of a substantial increase in the price of oil on equilibrium output, employment and oil consumption in the industry can be determined, on the assumption that the industry seeks to minimize its costs of production.

Such "state" equilibrium analysis has often been criticized for its lack of attention to the dynamic elements of adjustment to changes such as resource discovery, population change, technical innovation, managerial initiative and investment undertaken when future market conditions are uncertain. Critics also charge that such an analysis does not deal adequately with either sustained long-term national growth or the so-called Business Cycle of successive peaks and troughs in macroeconomic variables.

Criticisms

Among the critics are the post-Keynesian economists (see Keynesian Economics), who stress the dynamic analysis and emphasis on uncertainty in the work of John Maynard Keynes, a British economist who founded modern macroeconomics with his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). Other critics of formal mathematical equilibrium models stress the role of politics and institutions in economic affairs, often focusing on the inequality and dependency among persons, groups and nations which they see as characteristic of advanced industrial societies.

There are many such schools of thought, including Marxism, institutionalism, political economy and radical economics (see radical economics). For years many economics programs at Canadian universities were formally associated with political Science in departments of political economy or economics and politics. To the dismay of many institutionalist economists, most of such joint departments have by now been formally split.

Econometrics

Econometrics is the branch of economics that deals with statistical tests of economic theories. It has become an essential part of economic analysis over the past 3 decades, through its use in evaluating alternative policy decisions and theoretical models. Econometrics has been subject to criticism in recent years, primarily for the unfortunate practice of presenting statistical results from nonexperimental data as definitive, when in fact they are at best suggestive. There is concern about the advancement of economics as a scientific discipline, because of the fact that statistical tests are often inadequate for distinguishing among competing theories.

Canadian economics and economists are in constant interaction with economics and economists in the UK, Europe, the US and elsewhere, and it is thus no more possible to define "Canadian" economics today than it would be to define Canadian chemistry. Nonetheless the practice of economics in Canada has been strongly influenced by the distinctive demography and geography of the country - its large land base and relatively small population, and its proximity to a country with a national economy 10 times larger than its own.

Professional Economists

Professional economists generally specialize in one or more fields of the discipline, and Canadian economists have been particularly drawn to fields such as the economics of international trade and investment, resource economics and transportation economics. However, there is important work being done in Canada in all major fields of economics, including economic history, economic growth of underdeveloped economies, mathematical economics, industrial organization, labour economics, money and banking, public finance, urban and regional economics and econometrics.

Until the 1920s most writing on economics in Canada was done by government officials, businessmen, and citizens in other occupations concerned with certain issues of public policy, eg, the best methods of settlement on new lands, the relative advantages of free trade and tariff protection, and government control of currency and banking. Of the many pioneers of economics in Canada, 3 names stand out: Adam Shortt and William A. Mackintosh, both of Queen's University, and Harold Innis of the University of Toronto.

Shortt, appointed lecturer in political economy at Queen's, edited several volumes of documents on currency, finance and constitutional issues in Canada, and organized the remarkable 23-volume study, Canada and Its Provinces (1913-17), containing a wealth of material on Canadian economic development and public policy. W.A. Mackintosh edited volumes on western settlement and historical statistics but is best known as the author of The Economic Background of Dominion-Provincial Relations (1939), a classic economic history of post-Confederation Canada written as a background study for the Rowell-Sirois Royal Commission.

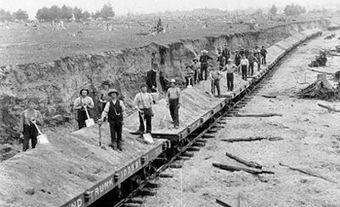

In 1930 Innis published The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History, a masterly survey of the importance of the trade in beaver furs in the 17th and 18th centuries and its decline in the face of the expanding settlement. His subsequent volume, The Cod Fisheries (1940), the book Empire and Communications (1950) and his many essays established him as Canada's most influential economic historian. Innis emphasized the role of staple exports - fur, fish, timber and wheat - in Canada's economic, political and social development, establishing what came to be known as the Staple Thesis.

International Trade and Investment

International trade and investment has long been an important area of research for Canadian economists. This area was surveyed in 1924 by Jacob Viner, a Montreal-born economist who taught at the University of Chicago and Princeton University, in his classic volume, Canada's Balance of International Indebtedness, 1900-1913. Canada's foremost trade economist was Harry G. Johnson, author of The Canadian Quandary (1977), who also wrote scores of articles on the pure theory of international trade, the Balance of Payments and Canadian economic policy with regard to international trade and investment.

Johnson, who published over 500 scientific papers and 19 books from 1947 to 1977, also made important contributions to macroeconomics, particularly in the areas of domestic and international monetary economics. Johnson's outspoken commitment to free trade and the free movement of international investment was not without its critics among Canadian nationalists, including Abraham Rotstein and Mel Watkins of University of Toronto, who argued that Canadian economic dependence on the US necessarily implied political and cultural dependence and led ultimately to a lowering of the Canadian standard of living.

Economic Research in French Canada

In the 20th century, French Canadian economic research has been centered at École des hautes études commerciales (HEC), founded in Montreal in 1970; Université de Montréal, which began its École des sciences sociales in 1921; and Université Laval, whose Faculté des sciences sociales was founded in 1938. HEC began publication of an economics journal, L'Actualité économique, in 1925, 10 years before the inauguration of the Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science in 1935, and 4 decades before that of the Canadian Journal of Economics in 1968.

Leading French Canadian economists from 1900 to 1945 included Robert Errol Bouchette, a civil servant, and Édouard Montpetit of HEC, both of whom wrote on the importance to French Canadian development of a knowledge of economics and participation in business affairs; Henry Laureys of HEC, who wrote on Canadian exports; and E. Minville, who wrote on social aspects of economic development in Quebec.

Important research after 1945 included that of Maurice Lamontagne and Albert Faucher, whose 1953 paper on the "History of Industrial Development" in Quebec explained the province's lag in industrialization in terms of geographical and technological factors, rather than cultural differences, an analysis developed at length in Faucher's Québec en Amérique au XIXe siècle (1973); that of André Raynauld, who wrote a classic study of Croissance et structure économiques de la province du Québec (1961); and that of Roger Dehem, who published widely in the field of economic theory.

There has been a virtual explosion of economic research in Canada over the last 3 decades, fuelled by a rapid expansion of graduate programs and a seemingly insatiable demand in the public and private sectors.

A taste of the wide variety of topics treated by Canadian economists is reflected in the annual Harold A. Innis Memorial Lecture, an invited public address by a distinguished economist to the Canadian Economics Association, which meets each spring. The lecture is published in the November issue of the Canadian Journal of Economics and generally contains an excellent bibliography of Canadian and foreign research on the topic in question.

Some of the issues dealt with since 1985 include the relation between public sector deficits, international capital movements and medium-term economic growth (Doug Purvis); the growing importance of Keynesian economic ideas in the 1980s (Peter Howitt); the effects on national income of 3 kinds of barriers to international trade: tariffs, quotas and voluntary export restraints (Peter Neary); macroeconomic policy designed to fight inflation and Canada's poor economic performance in the 1980's (Pierre Fortin); comparative economic growth among over 100 countries around the world (James Brander); how to overcome errors in economic data to make good economic judgments (John Cragg); the importance today of Harold Innis' theory of endogenous change in communication technology (Len Dudley).

Unemployment and Inflation

Perhaps the major reason for the growth of economics as a field of study over the past 3 decades has been its increasing importance in public-policy formation in areas such as taxation, income security, economic growth, resource development, and federal-provincial financial relations. The issues of unemployment and inflation illustrate the interaction between economics and public policy.

The Canadian economy in the 1970s was plagued by stagflation, ie, sharp increases in unemployment and inflation, and a sustained slowdown in the rate of growth of real output and productivity. Both problems led to a remarkable volume of theoretical and applied work in Canada. The most disconcerting aspect of the increases in unemployment and inflation was their temporal coincidence. Economists had been accustomed to thinking of unemployment and inflation as alternative evils to be avoided. It was not easy to explain the concurrent increase in both problems during the 1970s or to suggest how government policy should respond to the new economic development.

The dominant view of inflation and unemployment until the mid-1970s was summarized in the "Phillips Curve," which showed a negative relation between inflation and unemployment, with more of one implying less of the other. Periods of high unemployment in Canada, such as the 1930s, and the recession years of 1958 to 1962, tended to have low inflation, while inflation tended to accelerate in boom years with low unemployment, as in the period from 1947 to 1951 and in the late 1960s.

Much of the statistical work by Canadian economists was devoted to estimating the coefficients of the Phillips Curve, with a view to understanding how much inflation was necessary to lower the unemployment rate by one percent. The Phillips Curve literature in Canada is reviewed in S.F. Kaliski, The Trade-off Between Inflation and Unemployment: Some Explorations of the Recent Evidence for Canada (1972); among the best-known estimates in the 1960s were those of R.G. Bodkin et al in Price Stability and High Employment: The Options for Canadian Economic Policy (1966).

In the 1970s the simple trade-off between unemployment and inflation implied in the Phillips Curve broke down. The generally difficult conditions in Western economies since 1973 have had important effects on economic policy, by encouraging governments to experiment with innovative policies designed to return economies to growth and unemployment rates closer to those which prevailed in the 1950s and 1960s.

In Canada, the rate of growth of real gross national product fell markedly after 1973. The international oil price increases of 1972-73 and 1979-80 contributed greatly to the growth slowdown, as did the high nominal and real interest rates in Canada after 1977. The annual unemployment rate has been above 7 per cent since 1976, averaging 11.3 per cent from 1982 to 1985. Business capital spending fell by some 20 per cent from 1981 to 1983, and was still 10 per cent below the 1981 level 6 years later in 1987.

Economists differed greatly in their interpretation of these new trends. The Keynesians tended to focus on particular institutional and demographic events to explain the inflation of the 1970s, with special emphasis on the sharp increases in oil and other commodity prices in 1973-74 and 1979-80. They stressed the dangers of fighting such inflation with restrictive monetary policy and fiscal policy, which would result in unacceptable increases in the unemployment rate.

Unemployment had risen in part because of the large increases in the labour force as the Baby Boom generation entered the Labour Market, and as the participation of women in the Labour Force increased in an unprecedented manner. Some Keynesians therefore argued for a reimposition in the 1980s of the federal government's wage and price controls of 1975 to 1978, which they credited with slowing the inflation caused by the oil price shock of 1973-74. The Keynesian case is set out in Clarence Barber and J. McCallum, Unemployment and Inflation: The Canadian Experience (1980).

Monetarist economists had a very different view of inflation and unemployment, as explained in a volume by Thomas J. Courchene, Money, Inflation, and the Bank of Canada (1976). The monetarists argued that inflation was caused by excessive expansion of the Canadian money supply by the Bank of Canada, and that the bank should be charged with responsibility for fighting inflation by reducing the rate of growth of the money supply. In 1975 the governor of the Bank of Canada, Gerald Bouey, announced the adoption of monetarist principles in future bank policy, which would be directed at a gradual reduction in the growth of the money supply until inflation was eliminated.

This was easier said than done, and the next decade saw wide variations in inflation rates and monetary growth. By the late 1980s, however, determined Bank of Canada restraint under Governor John Crow brought down the rate of inflation to an average of about 1.6 per cent from 1991 to 1996, one of the lowest rates among advanced economies in the world. The political economy of this period is analyzed by David Laidler and Bill Robson in their 1993 volume, The Great Canadian Disinflation: The Economics and Politics of Monetary Policy in Canada, 1988-93. Critics of the Bank's policy, like Quebec economist Pierre Fortin, felt the cost in lost output and jobs was too great. In any case, by the mid-1990s there seemed to be a broad consensus among Canadian economists that having paid the cost of reaching what appeared to be a low and stable rate of inflation, it would be unwise to pursue policies that would restart the inflationary process.

One of the benefits of lower inflation was lower interest rates: for the 12 years from 1979 to 1990, the average annual rate on 90-day Treasury bills was never below 8 per cent and averaged 11.4 per cent; in early March of 1997, that same rate was about 3 per cent, well below the corresponding rate of 5.2 per cent in the US. Those low rates in early 1997 led to optimistic forecasts for growth and employment in Canada for 1997 and 1998, and hope that the country could bring down an unemployment rate which was still over 9.5 per cent in early 1997.

Economic Growth

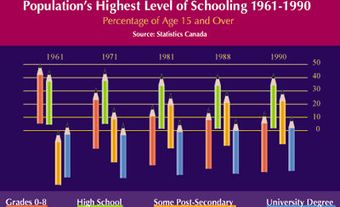

The rate of growth of real gross national product in Canada was 5.1 per cent in 1950-73, 3.4 per cent in 1973-86 and 2 per cent in 1986-96. This declining rate of growth, which was evident in most advanced economies, contributed to a renewed interest in the sources of long-term economic growth and productivity change. Growth theory in the 1960s and 1970s had tended to treat growth as due to non-economic "exogenous" changes in technology. By the 1990s, a school of growth had grown up which focused rather on "endogenous" sources of growth and change, due to business decisions on investment and risk-taking, and public support for education and research.

A widely accessible exposition of the "new growth theory" is contained in a 1995 paper written for Industry Canada, “Endogenous Innovation and Growth: Implications for Canada,” by Pierre Fortin and Elhanan Helpman, both members of the Program in Economic Growth and Policy of The Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. A third member of that Program, Peter Howitt, has urged the profession to abandon the tidy world of equilibrium growth models based on mathematical maximization and instead to model the behaviour of business firms according to the rules and procedures that firms actually follow, a position developed in his Presidential Address to the 1994 Canadian Economics Association, "Adjusting to Technological Change." Endogenous growth is closely related to the knowledge-based economy described by Peter Drucker, in which education, research and innovation are central to the growth process and in which teams of educated individuals sharing and co-ordinating specialized knowledge are at the heart of the modern business firm. A 1996 volume edited by Peter Howitt, The Implications of Knowledge-Based Growth for Micro-Economic Policies, contains some excellent papers on this theme.

Taxation and Government Spending

There is one area in which the monetarist and Keynesian schools have found much common ground, and that is on the importance of appropriate tax policies for optimal economic performance. Supply side economics, popularized in such books as George Gilder's Wealth and Poverty (1981), has laid special stress on the notion that high taxes reduce private incentives, and that tax cuts will stimulate effort and output.

In a similar manner, government policies designed to produce income security - such as unemployment insurance and welfare payments - may, if set too generously, produce an unwanted decline in the incentive to work. A common problem is the reduction of welfare payments by the amount of any earned income - such a 100 per cent tax on productive effort is a major disincentive to even part-time work in welfare families (see welfare state).

In Canada during the 1980s, both the federal government and the provinces were interested in using tax reform to produce better incentives for productive employment. A 1976 study, "People and Jobs," by the Economic Council of Canada argued for better co-ordination between tax and transfer policies and the goal of high employment. In 1984 the Quebec government issued a White Paper on the Personal Tax and Transfer System, with the goal of increasing work incentives while protecting those unable to work. While simulations tabled with the White Paper showed tax cuts producing impressive increases in employment, investment and output, the proposals were never put into law.

In June 1987, federal Finance Minister Michael Wilson introduced a White Paper on Tax Reform, designed to produce greater equity and simplicity in the tax system by removing many of the exemptions and deductions previously allowed on personal and corporate incomes, while at the same time reducing the tax rates in order to stimulate economic activity; overall tax collections were to remain unchanged (the proposed reforms were thus "revenue neutral").

The political problem faced by such reforms is that while in the abstract removing exemptions seems equitable, those industries and companies which stand to suffer real capital losses if the reforms are introduced will cry foul, and loudly. By far the most controversial of Mr. Wilson's proposed tax changes was the replacement of the Manufacturers Sales Tax (MST) by a federal government value added tax, the Goods and Services Tax (GST), which came into effect in 1991. The minister used economic theory to justify the change, arguing that the narrow base of the MST led to numerous economic distortions which would be eliminated with the GST. For many Canadians, however, the GST, which was visible on cash register receipts at retail stores, served to focus their frustration at the growing share of their incomes going to government, and their impression that government was not taking part in the economic retrenchment which seemed to be required of ordinary people.

Economists have long studied tax incidence, to determine who actually pays taxes and whether high-income families pay a higher share of their income in taxes. Recent work by W.I. Gillespie, A. Vermaeten and F. Vermaeten has shown that the overall tax burden rose from 27 per cent of income in 1951, to 34 per cent in 1969, to 37 per cent in 1988. In 1988 families with incomes of $10 000 to $16 000 paid about 30 per cent of their income in taxes; that figure was 38 per cent for those with incomes of $38 000 to $47 000 and 43 per cent for those with incomes over $175 000. The degree of progressiveness of the tax system did not change much from 1951 to 1988, although the tax rates for the poorest 10 per cent of families and the richest 2 per cent fell slightly. This kind of positive economic analysis leads naturally to the discussion of normative issues: should the tax system be more (or less) progressive? Should overall tax and spending rates be reduced? These questions were a central part of both provincial and federal election campaigns in Canada in the 1990s.

Canada is a federation, and the economics of federalism has long been a specialty of Canadian economists. The close result of the 1995 Québec Referendum has added urgency to efforts to find ways to share spending and taxing powers among the levels of government. In a 1994 study, Social Canada in the Millenium: Reform Imperatives and Restructuring Principles, Tom Courchene explores a number of changes to the Canadian federation, which he believes could reduce both political frictions and economic distortions. The politics of our federation will make this a hot topic for economists and others in coming years.

The growth in government spending in Canada became a central economic and political issue after 1985. Deficit budgets at both the provincial and federal level accumulated to the point that the ratio of debt to GDP in Canada in the early 1990s was one of the highest among advanced economies. At least one province, Saskatchewan, was near bankruptcy. Canadian fiscal policy in the 1990s focused on eliminating annual budget deficits and reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio. Severe budget cutting in several provinces - led by Alberta and Saskatchewan - produced surpluses in several provinces by the middle of the decade. In 1995 Ontario began an ambitious program of spending and tax cuts designed to promote growth and eliminate the deficit. At the federal level, the government led by Jean Chrétien cut spending on government programs and transfers to the provinces, so that the annual deficit fell below 2 per cent of GDP in 1997. Critics of the spending cuts felt that Canada was abandoning the disadvantaged of the country and threatening the future of our high-quality health and education systems; proponents of the cuts argued that governments had no choice but to bring down the cost of debt before it became unmanageable. These issues will undoubtedly be researched by economists and others over the coming years.

International Trade

The debate in the 1980s over free trade with the US is a good example of how economic and political issues get mixed in the formulation of public policy. The slow growth and high unemployment which characterized that decade seemed to strengthen the case in Canada for freer trade with the US, but the hard economic times also increased the fears of those concerned about job and income loss during the transition to freer trade. Proponents of free trade, including the Macdonald Commission, which issued its report in 1985, saw it as a necessary first step to returning the economy to higher growth rates of output, productivity and real incomes (see Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, Royal Commission on). Critics of free trade argued that with an unemployment rate above 10 per cent in the early 1980s, Canada could ill afford the additional unemployment which they saw as likely to follow free trade with the US.

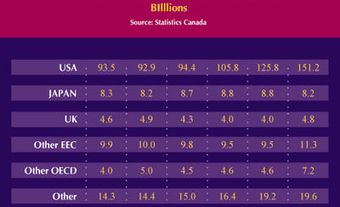

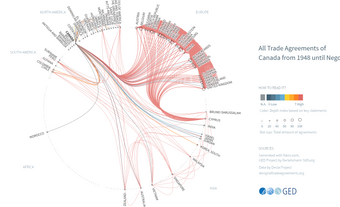

A decade after the signing of the FTA in 1987, there are still trade frictions between the US and Canada and the dispute-resolution mechanisms often seem slow and cumbersome, issues which are analyzed in a 1993 study by T.M. Boddez and M.J. Trebilcock, Unfinished Business: Reforming Trade Remedy Laws in North America. Yet most economists in Canada would declare the Agreement a success, as does Richard Lipsey in a 1995 paper entitled "The Case for the FTA and NAFTA." In current dollar terms, from 1991 to 1996, exports to the US increased by 104 per cent while exports to other countries grew by 45 per cent. During the same 5-year period personal consumption and fixed investment in Canada grew very slowly, so that exports kept a serious recession in the early 1990s from being much worse. With the inclusion of Mexico in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Canadian business is now seeking to expand markets in South America, Asia and Europe, as well as in the US and Mexico.

Future Trends

The future economic context for advanced industrial countries such as Canada will almost certainly include continued growth in the degree of international competition and the importance of international technological exchanges. As a relatively small country in economic terms, Canada needs to design economic policies which allow it to reap the greatest benefits from international competition and technological advances, while maintaining those social, political, cultural and regional institutions deemed vital to the identity of the country. The opportunities and dangers offered by the international economy will make future policymaking in Canada especially challenging.

The complexity of the modern global economy makes economics both an exciting and a difficult discipline. The turbulent economic times of the last 3 decades have led to much productive economic research and also taught many economists humility. As Harold Innis said, "Any exposition by any economist which explains the problems and their solutions with perfect clarity is certainly wrong."

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

_IMO_9785756,_Maasmond_pic.jpg)