Prior to 1871, in the province’s anglophone and francophone Catholic schools, the catechism was taught in the classroom, and members of religious orders, dressed in religious garb, generally served as teachers without having attended teacher’s colleges. But as of 1 January 1872, teachers had to have earned their teaching certificates in order to practice their profession. They also had to refrain from wearing or displaying religious objects or wearing religious garb. The ensuing debate became venomous, and New Brunswick Catholic schools were stripped of several rights that they had acquired over the preceding years. Section 93, paragraphs 3 and 4 of the recently passed British North America Act were supposed to place religious minorities in every province under the protection of the federal House of Commons, but the Canadian Parliament declined to enforce these provisions. The debate ultimately reached not only the House of Commons, where MPs Timothy Anglin and John Costigan called for the federal government to disallow the New Brunswick law, but also the Privy Council in London. Neither of these efforts was successful.

Catholic schools did secure some gains from these efforts, but John Sweeny, Bishop of Saint John, New Brunswick, tried for more. Some Catholics then refused to pay their school taxes. Tax collectors seized their possessions, and a few priests were imprisoned. A demonstration, orchestrated by Acadians, was held in Caraquet to protest the enforcement of the Common Schools Act. This demonstration degenerated into a riot that caused property damage. About a week later, Robert Young, the President of the Executive Council (provincial Cabinet), asked for the authorities’ help in arresting the rioters. Shots were exchanged between some Acadians and the police, leaving two dead: an Acadian civilian and a militia member.

Social and Political Context

The New Brunswick schools question resulted from a dilemma created by the Common Schools Act. Thiscontroversial law was intended to replace “separate” schools (which included all schools existing in the colony of New Brunswick before it joined Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada in Confederation) with public schools regulated by the province, in accordance with the British North America Act of 1867, which gave the provinces sole jurisdiction over education. At the opening session of the New Brunswick legislature on 5 April 1871, a discussion was placed on the agenda regarding a measure to introduce public schools during the next term, because the government deemed the existing school system to be inadequate.

Many criticisms had indeed been raised about the poor quality of instruction and low attendance in the province’s schools. It was in the majority-Catholic area around Gloucester that the rates of attendance were the lowest: during the preceding school year, under the former legislation (the Parish Schools Act of 1858), 882 students were registered, but only 489 attended school regularly. In fact, there was no law requiring parents to send their children to school, and in many cases only the most well-off families could afford to do so. The schools depended for funding on the taxes paid by the residents of each parish, so in the poorest parishes, the schools were underfunded and had trouble in attracting qualified teachers.

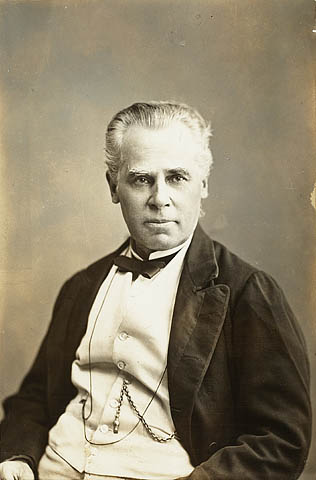

On 17 May 1871, the government of New Brunswick passed Bill 87, the Common Schools Act, to strengthen and reform the province’s school system. The province thereby abandoned the informal system of separate (denominational) schools that had developed as the result of some vague aspects of the Parish Schools Act (in particular regarding religious instruction in the province’s schools). The advocates of Bill 87, whose chief architect was provincial attorney general George E. King (who had also been the premier of New Brunswick, but resigned, then became premier again in July 1872), argued that mandatory, non-denominational schools would give all children in the province access to education. But many citizens of the province opposed the principle of free schooling; they said that children’s education was their parents’ responsibility and the government had no right to force children to attend public schools.

The main opponents of the Act were religious denominations such as the Anglicans and, more vehemently, French-speaking Catholics, for a variety of reasons. As of 1 January 1872, when the Act took effect, teachers in the province would have to refrain from wearing or exhibiting religious objects, including religious garb. They would also have to obtain provincial teaching certificates. Also, the French-speaking clergy saw instruction in French in separate schools as the only way to preserve the French language and French culture in the province. But the Common Schools Act, whichprohibited the teaching of religion in the schools, also denied the existence of the French language there. This upset Acadian nationalists, who expressed their outrage in the pages of the weekly newspaper Le Moniteur Acadien.

The Separate Schools Question and Confederation

At the London Conference of 1866, the delegates from the Maritimes opposed the Catholic bishops’ request that a system of separate schools be officially established in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as it had in Canada East (Québec) and Canada West (Ontario). These delegates believed that this decision should be left to the provincial legislatures and that the Catholics were a large enough group to defend their rights themselves in this context.

Before the British North America Actwas passed in 1867, each of the three provinces that were to form the Dominion of Canada — the Province of Canada (present-day Québec and Ontario), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia — had their own public school systems. Under section 93 of the BNA Act, each of these provinces retained sole jurisdiction over its school system. In addition, paragraph 1 of section 93 guaranteed that all denominational schools legally constituted at the time of Confederation would be permanently entitled to public funding. But although it was not explicitly stated, denominational schools that had been established in accordance with the customs of the time but had not been legally constituted would not be guaranteed the same rights. The provinces were therefore free to pass their own laws regarding schools, so long as these laws were consistent with the guarantees accorded to legally constituted denominational schools.

Debates in the House of Commons

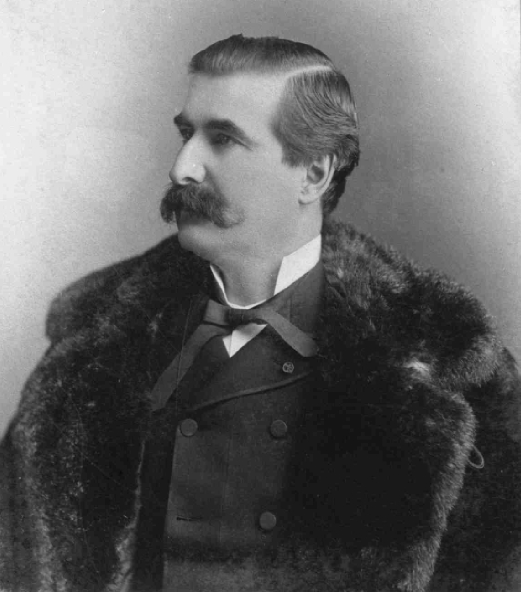

In 1872, the New Brunswick schools question was debated in the House of Commons. On 20 May 1872, John Costigan, Conservative member of Parliament for the riding of Victoria in New Brunswick and the son of Irish-Catholic immigrants, tabled a motion to disallow that province’s Common Schools Act. Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, who was then both the member of Parliament for Québec City and the premier of Québec, presented a proposal requesting that the Queen amend the British North America Act so as to protect the denominational schools in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Both proposals were rejected by the House.

The Conservative prime minister of Canada, Sir John A. Macdonald, along with several of his Cabinet ministers (including Sir George-Étienne Cartier and Sir Hector Langevin), refused to support these motions by members of his own party, for pragmatic reasons. First of all, Macdonald was aware of the influence that the Protestant Orange Order exerted on both his party and his voters. Federal elections were coming, and the Orange Order was categorically opposed to the recognition of a separate, Catholic school system in New Brunswick. Second, by disavowing Chauveau’s proposal, he anticipated a danger for the young Confederation and decided not to support the opponents, inviting them to be patient and arguing that education was a matter of provincial jurisdiction under the British North America Act. Also, the government of New Brunswick was threatening to leave Confederation if the House continued to debate the reform of that province’s school system.

Macdonald therefore suggested a compromise to his MPs. An amendment would be passed whereby New Brunswick Catholics would be guaranteed that their separate schools would be preserved — although they would not exist officially — without it being necessary to disallow the Common School Act. John Costigan was prepared to accept this solution, as were many Liberals who supported him. But this solution far exceeded the federal government’s jurisdiction. Another amendment was then introduced, deploring the situation of the Catholics of New Brunswick and expressing the hope that the provincial government would so something to improve it. This inoffensive resolution was passed, to the great displeasure of the Catholic bishops.

Meanwhile, the federal elections had changed the composition of the House of Commons. George-Étienne Cartier, who had supported Macdonald on the question of the Common Schools Act, lost his seat in the riding of Montreal East, while Honoré Mercier took a seat in Parliament. Hector Langevin continued to side with his prime minister. In a letter dated 12 May 1873 and addressed to his brother, Edmond Langevin, vicar general of the Diocese of Rimouski, Québec, he expressed his concerns about this issue in which Parliament was embroiled once more:

"Let us beware not to risk our constitutional rights, privileges and guarantees by making a futile attempt in England on behalf of the Catholics of New Brunswick. The Constitutional Act is a pact or treaty.… To alter it despite the majority of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick would be to pave the way and create a precedent for the intervention of the federal Parliament in our Lower Canadian affairs."

On 14 May 1873, Costigan tabled a motion in the House to disallow the new tax laws that New Brunswick had passed to fund its public school system. These laws were controversial to Catholics, because they forced them to pay taxes to fund a school system that they opposed. Costigan therefore asked that the matter be referred to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Mercier, in his very first speech in the House of Commons, supported the motion, drew some parallels among Canada’s various French-speaking minorities and expressed his support for the Catholics and francophones of New Brunswick. Despite the opposition of the prime minister and many conservative MPs, Costigan’s motion was carried by the House.

A few months later, on 5 November 1873, the government of John A. Macdonald was forced to resign in the wake of revelations regarding the Pacific Scandal, and the Liberal Party under Alexander Mackenzie took power. On 17 July 1874, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council found that the New Brunswick Common Schools Act was entirely constitutional and did not come under the committee’s jurisdiction. (At the start of 1873, the Supreme Court of New Brunswick had also confirmed the validity of this statute.)

The Caraquet Riots and the Resolution of the Crisis

Despite certain concessions granted to New Brunswick’s denominational schools, some of the province’s Catholics refused to pay the taxes designed to fund the public school system, in addition to those that they already had to pay to fund their parish schools. The tension peaked during the riots in Caraquet on 27 January 1875. The police, with the help of the militia, entered a house where the suspected rioters had taken refuge. Shots were exchanged, and two persons were killed: John Gifford (a militia member) and Louis Mailloux (a civilian).

The tragedy in Caraquet ‒ still remembered as a sad chapter in Acadia’s history ‒ clearly demonstrated the need to resolve the New Brunswick schools question. On 8 March 1875, Costigan made a final attempt to get the House of Commons to take a position on this issue. He moved that Parliament ask the Queen for an amendment to the British North America Act that would grant Catholics in New Brunswick the same education rights that minorities enjoyed in the provinces of Québec and Ontario. The Mackenzie government, still in power, opposed the motion, and it was defeated.

However, on 6 August 1875, the Executive Council of New Brunswick did make some amendments to the Common Schools Act that improved the situation for Catholics to some extent. In those areas where there were enough Catholic schoolchildren, school premises could now be used for Catholic religious instruction outside of regular school hours. Members of religious orders who taught in public schools were now allowed to wear religious garb while doing so and were no longer required to obtain teaching certificates from the province’s teacher training schools. Teachers could also communicate in their own language and had the right to teach French in the province’s primary schools.

However, these amendments did not provide truly separate schools for New Brunswick’s religious and linguistic minorities. Instead, an informal system similar to Nova Scotia’s was instituted, whereby a combination of contributions from federal, municipal and private sources was allocated to the denominational and non-denominational schools. The provincial school system was nevertheless a public one.

Instruction in French in the New Brunswick School System

In the 1940s, another wave of reforms took place in New Brunswick’s schools. In its report submitted in 1932, the MacFarlane Commission had encouraged the unification of the counties for purposes of taxation, the consolidation of the school districts and the allocation of grants. The Commission also insisted that children receive primary-school instruction in their mother tongue only. Although these reforms had a number of advantages for the province’s education system, including centralization of services, profound inequalities persisted among the inhabitants of the province’s various counties: the poorest were often the most heavily taxed.

In the 1960s, the government of Louis-Joseph Robichaud introduced further reforms. The Byrne-Boudreau Royal Commission was appointed in 1963 to shed light on how the province’s schools were financed. Following the publication of the commission’s report, the provincial government modified the funding of the education system so that it would henceforth be a provincial responsibility. In addition, from now on there would be two deputy ministers, one of them francophone, in the provincial Ministry of Education.

The early 1960s saw the founding of the Université de Moncton and the creation of a French-language teacher’s training school. In 1969, the Robichaud government passed the New Brunswick Official Languages Act, which introduced official bilingualism in the province, placing English and French on an equal legal footing. It was not until 1977, however, that all of the sections of this Act came into effect.

In 1979, New Brunswick implemented a system of education based on the language of instruction. As a result, two parallel school systems with similar structures were established, putting an end to bilingual schools and bilingual classes. Linguistic equity was enhanced when the government of Richard Bennett Hatfield adopted the Act Recognizing the Equality of the Two Official Linguistic Communities in New Brunswick . In addition, ever since the patriation of the Constitution and the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, section 23 of the Charter has guaranteed the members of the English or French linguistic minority of each province the right to primary and secondary school instruction in that minority’s language, to be paid for by public funds.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom