Early Social and Educational Context

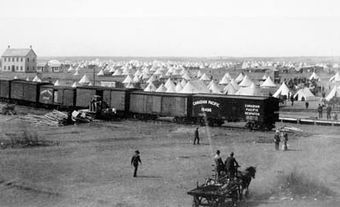

Until 1870, when the federal government obtained the North-West Territories from the Hudson’s Bay Company, formal education had been left to Christian missionaries. While there were a few Methodists, such as John Chantler McDougall, most were members of Roman Catholic religious orders such as the Grey Nuns and Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, including the notable Oblate Father Albert Lacombe. By the 1870s, French-Catholic settlers made up a majority of the non-Indigenous population in the region, and schools reflected their language and faith. Yet, beginning at this time, improvements in railway transportation and the potential for economic development (through farming and ranching) allowed for many new immigrants to the West. Most of the new settlers were English-speaking Protestants from Ontario, the United States, and the British Isles, who held a very different vision for the future of education.

Educational Developments in the 1870s and 1880s

In 1875, the federal Liberals, under the leadership of Alexander Mackenzie, enacted the North-West Territories Act. While maintaining the Canadian government’s authority, this document initiated the process of responsible government in the territory; a lieutenant-governor was installed and provisions were made for the introduction of elected officials when the population warranted. The Act also introduced the principle of separate schools for Protestant (mostly anglophone) and Catholic (mostly francophone) religious groups in the region. As such, local ratepayers were responsible for what type of school they wished to establish for their children. The 1884 School Ordinance guaranteed separate schools for religious minorities. While it mandated that the two denominational school systems operate within the Board of Education, each section had autonomy over key responsibilities, including curriculum, inspection and teacher certification in its own schools.

New Context for Educational Reform

This dual system remained in place until 1892. By that time, a series of developments had changed the educational landscape in the North-West Territories. First, a demographic shift meant that English-speaking Protestants had overtaken French-speaking Catholics in population. Second, with the introduction of a Legislative Assembly in 1888 and an Executive Committee in 1891, the region had more autonomy, and thus more political power for English officials to wield. Third, organizations such as the Equal Rights Association and the Orange Order mounted pressure across the country to attack French rights and Catholic education. Finally, in neighbouring Manitoba, Thomas Greenway’s Liberal government abolished official bilingualism and the separate school system in 1890, setting off a national controversy over educational rights, that tested the limits of the British North America Act (see Manitoba Schools Question). Given this new context, the idea of autonomous Protestant and Catholic educational sections in the North-West Territories grew increasingly unpopular. Many Protestants preferred that the Catholic minority not be granted any special educational privileges and that all children be educated together — regardless of language — to foster tolerance and civic unity and to rid the region of sectarian divisions.

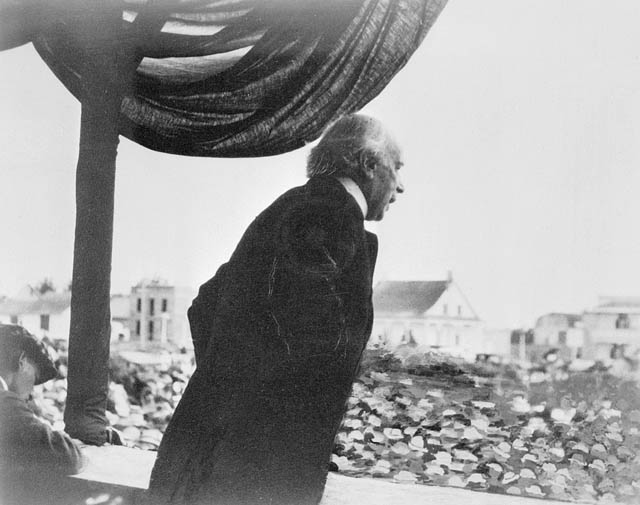

Educational Conflict

Under the leadership of F.W.G. Haultain, the leading politician in the territory between 1888 and 1905, the North-West Territories moved toward an English-only administration and educational system. Those who supported English-language schools thought it was the best means to induce patriotism and ensure the assimilation of French Canadians as well as the increasing number of European immigrants to the region in the 1890s, particularly the Ukrainians, Mennonites, Doukhobors, Germans and Scandinavians. Conversely, the Catholic clergy was vigorously opposed to any notion that they could not operate their own schools and were adamant that their faith and language was integral to school life. The leading advocates for Catholic education in the West were Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché of St. Boniface, Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin of St. Albert, and also Father Hippolyte Leduc.

To achieve their aims, Haultain and the Executive Committee introduced a series of school ordinances that concentrated educational authority in government hands and secured greater regulatory uniformity. Most importantly, the School Ordinance of 1892 saw the government limit clergy influence by taking sole authority over teacher training and certification, school inspection, and curriculum; by eliminating French-language instruction after the second grade; and by introducing a Council of Public Instruction to replace the Board of Education. Essentially, this legislation transformed denominational schools into a system of state-controlled “national” or public schools, with a few separate schools in which the religious influence became minimal. Catholic appeals to the federal government for more control over education went largely unheeded.

Renewed Controversy

The schools question was revived in 1904–05 during negotiations for provincial autonomy for Alberta and Saskatchewan. Early in 1905, amidst national controversy, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier introduced the Autonomy Bills. This legislation vaguely alluded to the possibility of restoring the dual system of schooling originally established in the 1884 Ordinance. Deep feelings on the matter, especially in Ontario and Québec, severely tested Canadian unity and threatened to split the Liberal Party. Indeed, Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton resigned from cabinet in protest. After his resignation, he proposed a compromise clause that Laurier accepted and which avoided the impending split. The clause, which became part of the constitutions of the new provinces, largely preserved the education conditions of 1892 and also reflected the 1901 Ordinance that further centralized school governance and put more limits on religious instruction.

Émile Legal, Grandin’s successor as the Bishop of St. Albert, was unwilling to follow Adélard Langevin (Taché’s successor as Archbishop of St. Boniface) into another round of opposition because he wanted to safeguard separate schools as they stood and avoid them having to face double taxation. Plus, with the Liberals in firm control of the first elections in the new provinces, there was little hope for Catholics attempting to secure more control. The North-West Schools Question quickly disappeared as a national issue. However, this controversy, along with the Manitoba Schools Question, the Ontario Schools Question and the New Brunswick Schools Question, was very important for the way it stirred religious and linguistic tensions, and reflected differing conceptions of Canadian identity. In the North-West Territories, the growing population of English-speaking residents sought to impose their will by limiting minority education rights and securing majority rule. This vision sharply contrasted with the French-Canadian struggle to form a bilingual and bicultural country. The North-West Schools Question, therefore, exposed some of the limitations of the Confederation agreement.

See also British North America Act, 1867: Document; History of Education; Second-Language Instruction.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom