Women’s movements (or, feminist movements) of the 19th and early-20th century — often referred to as first-wave feminism — included campaigns in support of temperance, women’s suffrage, pacifism, as well as labour and health rights. Mobilization and organizing by feminist activists during this period often focused on achieving legal and political equality.

This entry is the first of three histories of women’s movements in Canada. See also, Women’s Movements in Canada: 1960–85 and Women’s Movements in Canada: 1985–Present.

Groups and Causes

In the early and mid-19th century, most women in Canada collaborated with people like themselves. Given their socio-economic status, middle-class women of European origin had particular opportunities to organize. The groups formed by these women, such as missionary societies, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC), and the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (FNSJB), have attracted the most attention from scholars.

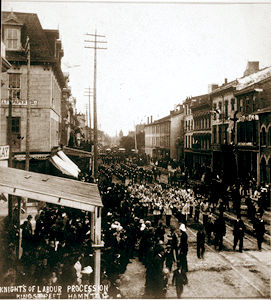

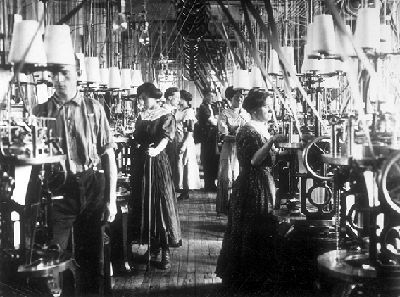

Many early activists prioritized women’s suffrage and the reform of societies dominated by Canada’s White, urban and male middle class. Although organized French- and English-speaking women often operated in what has been called “two solitudes” (that is, separate from one another and largely non-communicative), most assumed that a common capacity for motherhood meant they could speak for all women. Other groups — notably socialists, farm women and women of non-European origin — nevertheless wanted to speak for themselves. Black abolitionist Mary Ann Shadd championed women’s suffrage in her newspaper the Provincial Freeman, inserting her voice into an overwhelmingly White, feminist cause. On the other hand, Mohawk-English poet E. Pauline Johnson was not willing to publicly endorse suffrage, a stance that was more typical among women at this time. Some marginalized women seized the initiative through groups such as the Knights of Labor (beginning in 1886) and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (beginning in 1900). Some mainstream causes of the early women’s movements, such as reforms in family law, education, public health and employment, were of broad benefit.

Early coalitions of women’s groups, such as the NCWC (established in 1893) and the FNSJB (1907), recognized and represented relatively diverse concerns and causes, demonstrating the promise of a common voice. The potential of broad coalitions was and continues to be a significant theme in Canadian women’s movements.

Women’s Suffrage and Human Rights

When the First World War ended in 1918, and most women in Canada won the right to vote, organized women were often uncertain about how to proceed (see Women’s Organizations). There was some debate as to whether they should organize as independent and non-partisan groups, establish separate women’s political parties, or improve male groups with insights based on female experiences. Few separate political groups emerged, but women formed new associations of their own and often joined men in social and political campaigns, for example in the League of Nations, the Communist Party of Canada, the Canadian Birth Control League and the Canadian Red Cross Society. New women-only opportunities emerged in the National Council of Jewish Women of Canada, the Canadian Negro Women’s Association, the Federated Women’s Institutes of Canada, Women’s Labour Leagues, and the Catholic Women’s League of Canada. Some, like the Women’s Missionary Society of the United Church operated almost independent female worlds. Secular patriotism mobilized the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire and the Women’s Canadian Clubs — both founded in the early 20th century. The Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada offered members another form of nationalism. The Canadian Federation of University Women called for equality in education and employment. Unions such as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers supported women workers. So too did groups such as the Canadian National Association of Trained Nurses and the Federation of Women Teachers’ Associations of Ontario. The Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs emerged alongside the international federation in 1930, and demanded employment equality.

The suffrage cause continued to mobilize women in provinces that had yet to extend the right to women. In Québec, the Alliance canadienne pour le vote des femmes du Québec and the Ligue des droits de la femme led the charge until women’s suffrage was achieved in 1940.

Where they possessed the vote, women mobilized in groups such as Toronto’s Women Electors Association and Vancouver’s Women’s Forum. Much like unions, the Conservative, Liberal, Social Credit and Communist Parties, and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation offered opportunities, usually very limited, for women-only and mixed gender campaigns. Women committed to internationalism joined the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and groups such as the Canadian National Committee on Refugees and the Canadian Peace Congress. Contacts with American civil rights and anti-imperialist campaigns put WILPF in the forefront of Canadians opposed to racism.

Broad national coalitions such as the NCWC remained significant in feminist causes such as the Persons Case (1929) and the retention of married women’s citizenship (1947). Women also sought local partnerships in familiar groups such as the local councils of women and in newcomers such as the Mothers’ Council of Vancouver during the Great Depression.

While the years before 1960 did not mobilize women to better society and government as powerfully as the suffrage cause, they were not fruitless. The emergence of social security owed much to cooperative endeavours, beginning with mothers’ pensions during the First World War, old-age pensions in 1927, and the creation of the federal Women’s Labour Bureau in 1954. Organized women challenged opposition to equal pay, endemic violence against women and children, and lack of support for female politicians. While few publicly named themselves feminists, activists remained critical community builders.

Mainstream women’s groups largely took Whiteness, class and heterosexuality for granted. Indigenous and other racialized women worked within their own communities. Even Canada’s “two founding peoples,” as they were termed, had few contacts. The ignorance and arrogance that poisoned so many French-English relations resembled problems later highlighted between White women and women of colour. For many years, lesbian and trans-women faced pervasive (though often less visible than racial) prejudice, which was not in widespread retreat until the 21st century.

Significance and Legacy

The early women’s movements offer reminders of courage, diversity and frequently conflicting agendas among activists. They also suggest the potential and the problems of creating broad-based coalitions to challenge sexism and misogyny. Too often, special interests — whether of class, race, religion, or ability — undermined activism. Ultimately, the struggle for women’s rights or feminism never attracted all women; loyalties, distrust, or fears kept many silent or in opposing camps. Activists’ long, and often unfinished, struggles for a better deal in education, law, employment and healthcare confirm that inequality is ongoing.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom