Since the late 1960s, the 2SLGBTQ+ community in Canada has seen steady gains in rights. While discrimination against 2SLGBTQ+ people persists in many places, major strides toward mainstream social acceptance and formal legal equality have nonetheless been made in recent decades. Canada is internationally regarded as a leader in this field. Recent years have seen steady progress on everything from health care to the right to adopt. In 2005, Canada became the fourth country worldwide to legalize same-sex marriage.

Background

Britain held immense sway over Canadian policy throughout the many years in which homosexuality was criminalized. Dating from the early colonial era, homosexuality was officially illegal and the penalty for “the abominable act of buggery” (also known as sodomy) was punishable by death. In 1861, that law was moderated slightly, when the sentence became imprisonment for a period of 10 years to life. For the next century, however, the laws governing “homosexual acts” in became more and more stringent. They were almost always targeted at men, and by using consistently ambiguous language tended to give a tremendous amount of discretionary power to law enforcement. Beginning in 1890, accused gays were usually charged with the crime of “gross indecency.” Amendments to the criminal code were made in 1948 and 1961, which further criminalized homosexuality through the invented categories of “criminal sexual psychopath” and “dangerous sexual offender.” (The definition of the latter was anyone “who is likely to commit another sexual offence,” thus criminalizing any gay person who was not celibate.)

Two important events precipitated the liberalization of Canadian laws and attitudes in the late 1960s. The first of these was the imprisonment of Everett George Klippert, a mechanic from the Northwest Territories arrested in 1965 on charges of “gross indecency.” After being deemed a “dangerous sexual offender” by prison psychiatrists, his prison term was extended indefinitely — a ruling that was scrutinized and criticized in the mainstream press.

The second was the British parliament’s decision to decriminalize certain homosexual offenses. Debate on the issue had been escalating in both British and Canadian media through the previous decade, following the release in 1957 of a public inquiry known as the Wolfenden Report, which recommended decriminalization. In the summer of 1967, those recommendations were finally adopted, and with the embarrassing Klippert controversy still ongoing, several members of Canada’s parliament, including Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau, began calling for reform. Following Trudeau’s election to the prime minister’s office, his government passed Bill C-150 in May 1969, decriminalizing gay sex for the first time in Canada’s history.

Gay Liberation in the 1970s

The modern gay liberation movement in North America began in the summer of 1969 with New York City’s unprecedented Stonewall Riots, which took place in the early morning of 28 June. The New York Police Department had attempted a raid on a popular gay bar in the heart of Greenwich Village that night, but the bar’s patrons fought back forcefully, resulting in a humiliating defeat for the police and garnering nation-wide media attention. On the first anniversary of the riots, marches took place in New York, Boston, Minneapolis, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The movement simultaneously gained momentum in Canada. In August 1971, the first protests for gay rights took place with small demonstrations in Ottawa and Vancouver demanding an end to all forms of state discrimination against gays and lesbians. One year later, Toronto held its first Pride celebration with a picnic on the Toronto Islands organized by the University of Toronto Homophile Association, Toronto Gay Action Now and the Community Homophile Association of Toronto.

The early 1970s also saw the emergence of Canada's first gay publication, The Body Politic, established in Toronto in 1971 and published until 1987. Today, its publisher, Pink Triangle Press, puts out Daily Xtra, with editions in Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver. Pink Triangle Press also founded the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives in 1973, which today is a respected and historically important collection of 2SLGBTQ+ material.

DID YOU KNOW?

2SLGBTQ+ is an umbrella term that stands for people who are two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning), and additional sexual orientations and gender identities, such as intersex and asexual.

One of The Body Politic's most significant episodes occurred in 1978. Pink Triangle Press was charged with “possession of obscene material for the purpose of distribution” in response to an article on pederasty titled “Men Loving Boys Loving Men.” The case was finally resolved in 1983, when the Crown declined to appeal a second acquittal. Thomas Mercer, the judge in the second trial, ruled that the article “does, in fact, advocate pedophilia,” but stated, “It is perfectly legal to advocate what in itself would be unacceptable to most Canadians.”

The late 1970s also saw two major legislative changes. In 1977, Quebec amended its Human Rights Code to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. That same year, the Canadian Immigration Act was also amended, lifting a ban prohibiting gay men from immigrating.

The 1980s

Though 2SLGBTQ+ rights were advancing, gays and lesbians still faced discrimination, including ongoing police harassment. In 1981, tensions came to a head in Toronto in what became known as Canada's Stonewall.

On 5 February 1981, Toronto police arrested almost 300 men in raids on four bathhouses. The following day, a crowd of 3,000 people took to the streets and marched on 52 Division police precinct and Queen’s Park, smashing car windows and setting fires en route.

The men were charged with being “found-ins” in a bawdy-house, which police defined as being any location where “indecent acts” took place. The vast majority of the charges were thrown out. Such raids continued over the next 20 years in Canada, including a 2002 raid on a Calgary bathhouse. In Toronto, where the relationship with police was particularly fraught, the raids culminated in a police sweep of the Pussy Palace, a women-only event, in 2000. Charges were dismissed, and the resulting lawsuit led to the development of training programs for Toronto police on interacting with the 2SLGBTQ+ community.

The 1981 raids led to the establishment of Lesbian and Gay Pride Day in Toronto, which attracted 1,500 participants that same year. (The City of Toronto did not endorse Pride until 1991.) Since then, Pride has been held annually in Toronto and several cities across the country.

The 1980s also saw a number of major legal victories. In 1982, Canada repatriated its Constitution and adopted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which became the basis for many future equality decisions. In 1985, Section 15 of the Charter came into effect, guaranteeing the "right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability” — it did not, however, include sexual orientation.

Provincial human rights codes continued to expand. Following Québec's 1977 lead, Ontario added sexual orientation to its Human Rights Code in 1986, and Manitoba and the Yukon followed suit the following year. It was not until 1998, however, that the definitive word on provincial human rights was written. In that year, the Supreme Court ruled that Alberta's human rights legislation must be considered to cover sexual orientation. The ruling came in the case of Delwin Vriend, a teacher fired for being gay.

In the spring of 1988, British Columbia MP Svend Robinson came out as Canada's first openly gay member of parliament.

The HIV/AIDS Crisis

The 1980s also saw the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Canada, which would have a devastating impact on the gay community. Throughout the decade, gay men felt that their health was being ignored by the medical establishment and the government and increasingly took matters into their own hands.

As the crisis escalated, the movement became more organized and politically proactive. In 1983, AIDS Vancouver became Canada's first AIDS service organization, offering care to those with HIV or AIDS. The same year, in Toronto, Gays in Health Care, the Hassle Free Clinic and The Body Politic united to form the Toronto AIDS Committee, soon renamed the AIDS Committee of Toronto. Another watershed moment came in 1988, with the establishment of AIDS Action Now (AAN), a group that adopted direct action as a means of pressuring governments to take meaningful steps to address the crisis.

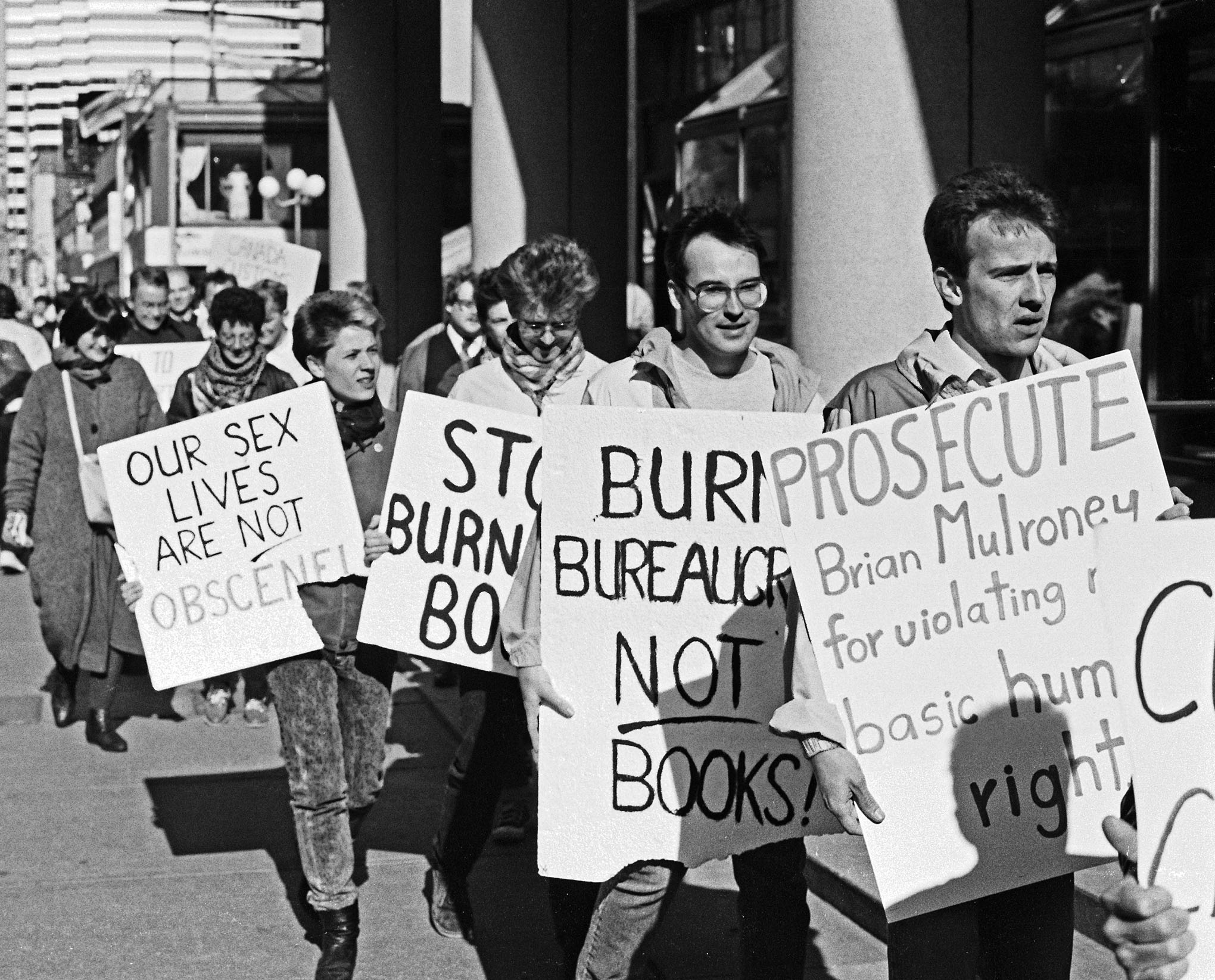

The first AAN action was a protest against a Toronto drug trial for Pentamidine, a drug already approved for American AIDS patients. AAN brought coffins to the Toronto General Hospital where the research was taking place, demanding that the drug be made immediately available. The protests were successful, and within two years the government of Brian Mulroney implemented a program granting access to experimental drugs and the launch of the first national AIDS strategy.

AAN established its own treatment registry, the Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, which continues to work with health services across the country such as the Prisoners HIV/AIDS Support Action Network, and the HIV/AIDS Legal Clinic of Ontario.

The effect of HIV/AIDS continues to be felt; the Public Health Agency of Canada estimated that approximately 63,000 Canadians were living with the disease at the end of 2016. It is disproportionately prevalent not only among gay men but also among Indigenous persons and people from countries where HIV is endemic.

The epidemic’s effect of stigmatizing gay men has also persisted and in many ways. In the mid-1980s, the Red Cross, which then ran Canada's blood donor system, instituted a rule that any man who had had sex even once with another man since 1977 could not donate blood. That rule remained in effect until 2013, when it was amended so that men could donate if they hadn't had sex with another man for five years. In 2016, Canadian Blood Services, which now runs the blood donor system, reduced the ineligibility period from five years to one year. Héma-Québec, which manages the blood donor system in Quebec, also reduced the ineligibility period at that time.

The 1990s and 2000s

A cascade of legal victories for 2SLGBTQ+ people followed from precedents set in the 1980s. As gays and lesbians were increasingly represented in the public sphere, these changes reflected the community’s continued and growing acceptance into mainstream Canadian culture.

Several of these victories were won in the courts. Among them was a 1992 federal court ruling that lifted the ban on gays and lesbians in the military (see Canadian Armed Forces); a 1994 Supreme Court ruling that gays and lesbians could apply for refugee status on the basis of facing persecution in their countries of origin (see 2SLGBTQ+ Refugees in Canada); and a 1995 ruling in Ontario that allowed same-sex couples to adopt.

Also in 1995, the Supreme Court ruled that Section 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees the "right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination,” included sexual orientation as a prohibited basis of discrimination. This ruling was the result of a case brought to the Supreme Court by Jim Egan and Jack Nesbit, who were appealing a decision by Health and Welfare Canada to deny Nesbit the spousal benefit under the Old Age Security Act. Although Egan and Nesbit lost their appeal, the Supreme Court’s ruling that sexual orientation was protected under the Charter paved the way for future legal challenges to discriminatory policies. The following year, sexual orientation was added to the Canadian Human Rights Act, which covers federally-regulated activities.

In 1999, the Supreme Court ruled in a case known as M v. H that same-sex couples must be afforded the same rights as opposite-sex couples in a common-law relationship. In 2000, the federal government passed Bill C-23, which brought federal statutes into line with the ruling.

In 2000, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of Vancouver's Little Sister's bookstore that gay publications, even sexually explicit ones, were protected under freedom of speech provisions in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The store had filed suit against Canada Customs for repeated seizures of 2SLGBTQ+ material. The problem persists, however, with gay bookstores alleging that Customs guards disproportionately cite the Supreme Court's 1992 Butler decision against gay and lesbian publications. That decision ruled that material containing scenes of sex mixed with violence and cruelty could be seized.

These years were also marked by the emergence of several openly gay and lesbian politicians. In 1998, Glenn Murray became the first openly gay mayor of a major city in North America when he was elected mayor of Winnipeg. In 2001, NDP MP Libby Davies became the country's first openly lesbian member of parliament. In 2004, Scott Brison became the country's first openly gay cabinet minister. Another milestone would later be reached when Kathleen Wynne became the first openly gay or lesbian premier in 2013 when she was selected as the new leader of the Ontario Liberal Party. In spring 2014, she became the first openly gay or lesbian premier elected to office in Canada.

Much of the early 2000’s news for 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians revolved around the issue of same-sex marriage. In 2002, the Ontario Superior Court ruled that prohibiting same-sex marriage was a violation of Charter rights. The ruling was followed in 2003 by a similar ruling in British Columbia. In 2003, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the ruling, and Michael Leshner and Michael Stark became the first same-sex couple to marry in Canada.

By 2005, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Alberta and PEI were the only jurisdictions not allowing same-sex marriage. On 20 July of that year, Bill C-38 became federal law, making Canada the fourth country in the world to allow same-sex marriage.

In 2008, Canada increased the age of sexual consent from 14 to 16. The age of consent for anal sex, however, remains at 18, leading to charges of discrimination against gay youth.

The 2010s and Beyond

In the 2010s, many of the issues facing the 2SLGBTQ+ community revolved around youth and transgender people, with protection from bullying and gender identity becoming major causes.

Addressing bullying in schools became a major issue for gays and lesbians in Canada. While a number of provinces passed anti-bullying legislation, laws in Ontario and Manitoba — passed in 2012 and 2013, respectively — require that all publicly-funded schools, including religious ones, accept student-organized gay-straight alliances.

The rights of trans people in Canada continue to be at the forefront of the struggle for equality. In 2017, the federal government passed Bill C-16, which amended the Canadian Human Rights Act to include gender identity and gender expression as prohibited grounds of discrimination. It also added gender identity and expression to the Criminal Code. The legislation therefore provides better protection against hate propaganda and hate crimes directed against trans and gender-diverse individuals. All provinces and territories also explicitly include gender identity under their human rights codes.

Transgender activists have also fought to make it easier to change their gender on official documents, without having to have actually undergone gender reassignment surgery. Ontario's Human Rights Tribunal struck down the surgical provision in 2012, the BC legislature and an Alberta court followed suit in 2014. The Manitoba government struck down the surgical provision in 2015. By 2018, all other provinces and territories had followed suit.

The clash between 2SLGBTQ+ rights and religious freedom has also come to the fore. Trinity Western University (TWU), a private Christian institution in British Columbia, wanted to open a law school beginning in 2016. The application had been approved by both the British Columbia government and the Federation of Law Societies of Canada. However, law societies in Ontario, Nova Scotia and British Columbia said they would not recognize graduates because of the school's community covenant, which mandates that students abstain from sexual intimacy “that violates the sacredness of marriage between a man and a woman.” In both Nova Scotia and British Columbia, the courts sided with TWU, but the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled against the school, calling the mandatory covenant “deeply discriminatory to the 2SLGBTQ+ community." In 2017, both TWU and the Law Society of B.C. appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. In June 2018, a majority of Supreme Court justices found that law societies had the power to refuse accreditation based on TWU’s mandatory covenant. In August 2018, TWU dropped its requirement that all students sign the covenant.

In December 2021, members from the House of Commons voted unanimously to ban conversion therapies.

With the steady increase in rights for 2SLGBTQ+ Canadians, the focus of many has turned to the situation of gays and lesbians abroad who face more violent persecution. Such cases have become a focus for many of today's Pride celebrations. This culminated in 2014, when Toronto hosted the fourth WorldPride Event, which included a week-long human rights conference.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom