Rebellion of Upper Canada

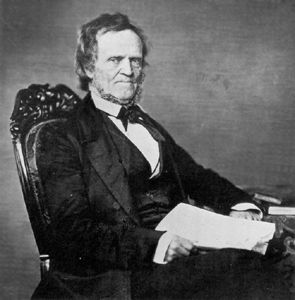

In early December 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie, a politician and publisher of Scottish origin, started a rebellion against the British government in the province of Upper Canada. For years, he had been overtly criticizing the Family Compact, a network of public servants and businessmen that had dominated the colony’s government since the beginning of the 19th century. After unsuccessful attempts at peaceful change, Mackenzie convinced his most radical followers to try to seize control of the government and declare the colony a republic.

On 5 December 1837, confident that people would spontaneously support him, he marched with a group of rebels down Yonge Street, planning to reach the house of Lieutenant-Governor Sir Francis Bond Head, and perhaps Toronto’s City Hall. Fortunately for Sir Bond Head, the colonel and loyalistAllan Napier MacNab, accompanied by a few hundred Hamilton militia members, reached Toronto first, causing Mackenzie’s troops to retreat. A few days later, on 8 December, the loyalist troops under the command of Samuel Jarvis marched to Montgomery’s Tavern, the rebels’ headquarters, and easily dispersed them.

Rebels Escape to Navy Island

On the run, Mackenzie crossed the Niagara River. Shortly after, with about 200 American and Canadian followers, he set camp on Navy Island, on the Canadian side of the river, intending to prepare an attack. He formed a provisional government there and issued a proclamation calling for a Republican-style democratic reform. A small steamboat, the Caroline, transported supplies to the rebels from the American shore.

Sir Bond Head sent Allan MacNab and his militia forces to control the Niagara border. MacNab, a rich Hamilton lawyer and one of the Family Compact pillars, was a veteran of the War of 1812. On 29 December 1837, he ordered Andrew Drew, a Royal Navy commander, to dispose of the Caroline.

Burning of the Caroline

That same evening, Drew and a hand-picked group of militia members rowed out to Navy Island and discovered that the Caroline was already gone. Then they decided to cross the river and found the steamer safely moored under the cannons of Fort Schlosser. In minutes, Drew and his men boarded, killed a watchman, cut the mooring cables and set the Caroline on fire. As the vessel drifted downstream, toward Niagara Falls, the flames lit up the night sky and guided Drew and his men back to Upper Canada.

The Americans regarded the intrusion in their territorial waters, the destruction of one of their vessels and the murder of the watchman as acts of piracy. For the British, this was rather a punitive action against Mackenzie’s troops, whose activities should have been stopped by the American authorities.

The United States government quickly requested financial compensation for the loss of the ship, and Commander Drew was accused of murder by an American court. However, he remained on duty as naval adviser to MacNab and then to his successor, William Sandom. In the summer of 1839, he was removed from command for being absent without leave and signing a false muster roll. In 1842, fearing for his life due to his role in the Caroline incident, he decided to return to England, and served again in the Royal Navy.

William Lyon Mackenzie moved to New York, where he founded the newspaper Mackenzie’s Gazette. He was found guilty of violating the United States neutrality laws and imprisoned for a year. He was not allowed to return to Upper Canada until 1849, when he was granted a pardon.

Consequences

The Caroline incident had a serious impact on British-American relations and marked the beginning of a period of instability at the border, in particular in the Great Lakes region (see Canadian-American Relations). In the summer and autumn of 1838, the Hunters’ Lodges launched a series of attacks against Upper Canada and Lower Canada to free Canadians of the “British tyranny.” The Rebellions of 1837 entered a harsher and bloodier second phase. It wasn’t until December 1838, after a stern reminder from American president Martin Van Buren of the neutrality law with respect to Canadian affairs, that the threat seemed to subside. The Hunters’ Lodges were gradually disbanded and became obsolete after the signing of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty (9 August 1842) between the United Kingdom and the United States, which aimed to settle their borders disputes.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom