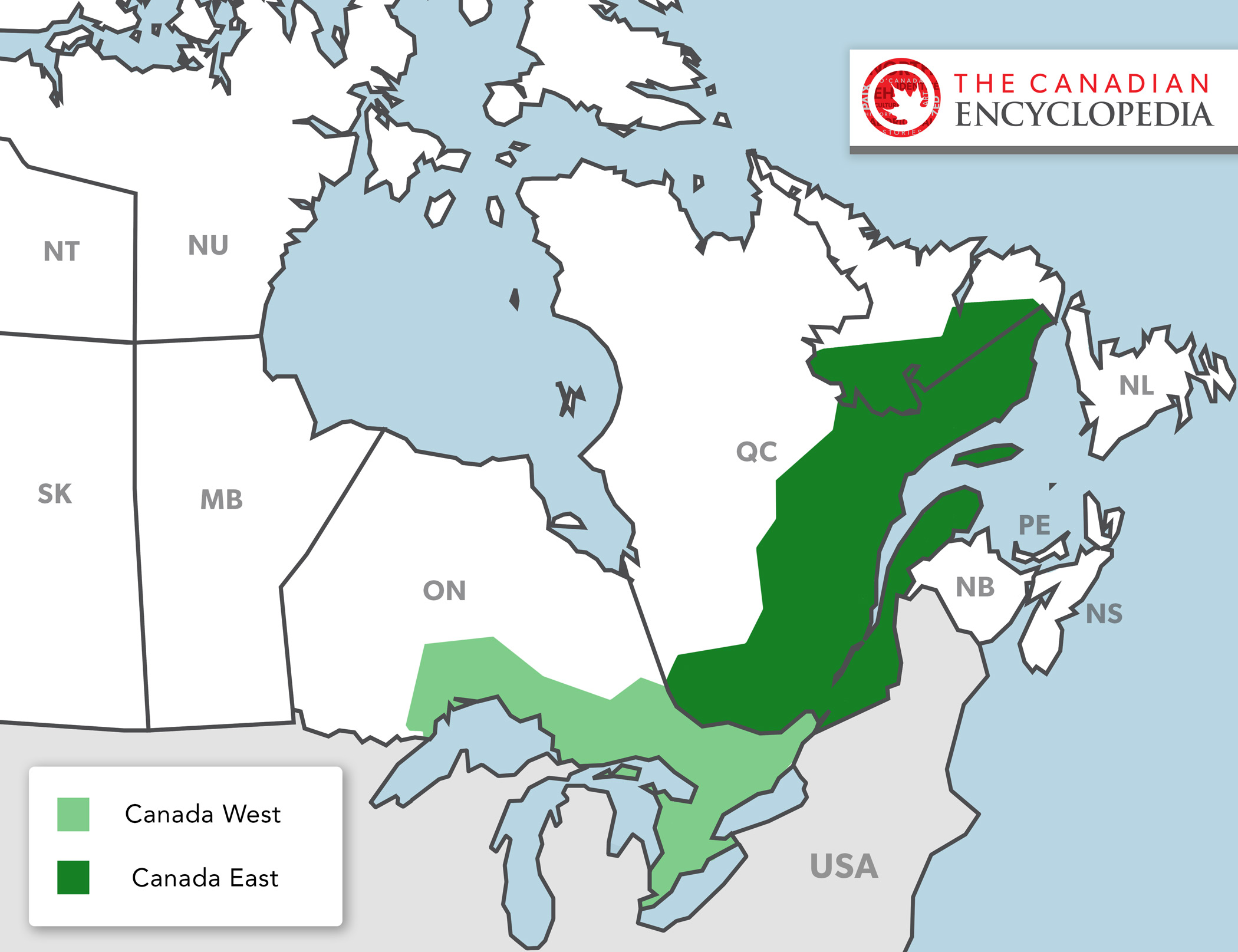

In 1841, Britain combined the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada into a single colony called the Province of Canada. The colony had two regions: Canada West (formerly Upper Canada), and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada).

Geography and Population

Canada East reached from Montreal and the Eastern Townships in the south, along both sides of the St. Lawrence River, to the Gaspé peninsula in the northeast and the Ottawa River in the west. Rupert's Land, to the northwest, was chartered to the Hudson's Bay Company.

The population of Canada East in 1840 was estimated to be 670,000. About 510,000 people were French Canadians. Their families had lived in the region for more than 200 years. The rest were Indigenous people, whose ancestors had lived there for thousands of years, and Loyalist settlers who had fled the American Revolutionary War (1775–83). Loyalists formed the core of an English-speaking community. Its numbers expanded rapidly through waves of English and Scottish immigration.

Governance

Britain had hoped that uniting Upper and Lower Canada would assimilate the French-Canadian population into the overall English-speaking majority of the Province of Canada. Both Canada East and West were given equal numbers of seats in the colonial legislature, even though the East’s population was at first significantly larger (670,000 compared to 480,000 in Canada West). Canada East was therefore underrepresented on the political stage. Real political power, however, resided in the British governor. He ruled the two provinces with an appointed executive council.

Society and Economy

A minority Anglophone merchant class largely controlled the economy. They ran the timber, canal and railway companies, banks, trading houses and other businesses based in Montreal.

French-speaking society in Canada East was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church and clergy. They also largely controlled matters of education. Most French habitants were farmers, woodcutters and labourers. The French civil legal code was maintained, along with the seigneurial land system of tenant farming. However, the latter was abolished (in law if not in practice) by 1854.

In the 1840s, a worldwide economic depression brought hard times to Canada East. The province was also coping with the decline of the fur trade. It had been the region’s economic foundation for centuries. By the 1850s, however, the economy was growing again. It was spurred on by the industrial revolution, the expansion of canals on the St. Lawrence, and the construction of railways between Quebec City, Montreal, Toronto and the US. The 1854 Reciprocity Treaty ( free trade) with the US also opened access to American markets for Canadian timber, grain, fish and textiles.

Montreal Riots

In 1848, a political reform movement replaced the conservative forces that had long controlled the elected assembly. The movement was led by Robert Baldwin in Canada West and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine in Canada East. Along with reformers in Nova Scotia, the co-premiers convinced imperial leaders in Britain to grant responsible government to the British North American colonies. As a result, LaFontaine and Baldwin led the Province of Canada's first executive council, or Cabinet, that was responsible to the elected legislature and not a colonial governor.

One of the new government’s first measures was the 1849 Rebellion Losses Bill. It was meant to compensate those in Canada East who had lost property or suffered damages in the Rebellion of 1837. French Canadians viewed the Bill as social justice. English-speaking conservatives saw it as a rewarding of rebels. Despite this anger, the British governor, Lord Elgin, signed the Bill into law. After all, it had been approved by the legislature then sitting in Montreal, under the new system of responsible government.

Protests over the matter culminated in the Montreal Riots in the winter of 1849. Elgin himself was attacked and the parliament building was burned down. As a result, the government relocated the seat of government to Toronto. Never again would Montreal be a political capital.

Rep by Pop

The riots fueled sentiments among English Canadians that Canada East was now over-represented in the legislature. This led to calls for true representation by population. In the 1840s, Canada West benefitted from having a disproportionately large number of seats, thanks to a smaller population. By the 1850s, its population was the bigger of the two. Reformers such as George Brown, Reform Party Leader and editor of Toronto's Globe newspaper, strongly supported the campaign for representation by population. This would mean more seats for Canada West.

Political Deadlock

This and other divisive issues — such as government funding for Catholic schools throughout the colony — made English Protestants in Canada West suspicious of unchecked French Catholic power. Many French Canadians, on the other hand, viewed such matters as a struggle for cultural survival.

The rift between English and French created years of unstable government and political deadlock. The situation was worsened by a growing divide between conservatives and reformers within Canada West. This made addressing the colony's needs and problems nearly impossible. By 1859, Structural change was required to break the political paralysis.

Creation of Quebec

In 1864, an unlikely Great Coalition sought to solve Canada's problems. The coalition included reformers led by George Brown, and conservatives led by John A. Macdonald in Canada West and George-Etienne Cartier in Canada East. They decided to create a new federation of all British North American colonies. Negotiations began with the Maritime colonies at the Charlottetown Conference in 1864. By 1867, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick agreed to enter Confederation with the two Canadas.

With Confederation in 1867, the Province of Canada was dissolved. Canada West became the province of Ontario and Canada East became the province of Quebec. Its legislature and capital were located in Quebec City.

See also: Quebec and Confederation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom