More than a century ago, francophones in Ontario established an organization that has claimed and defended their rights in nearly every sector: education, arts and culture, economy, health and legal services. The story of Franco-Ontarian representation is one of a community that is both deeply rooted in its province and open to newcomers, regardless of their origins.

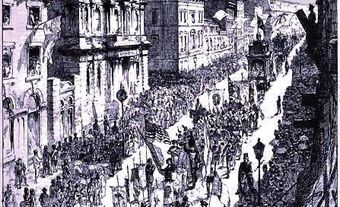

1910 Convention: Grand Congrès des Canadiens français de l’Ontario

From 18 to 20 January 1910, 1,200 delegates, representing the 210,000 francophones in Ontario, gathered at the Monument National in Ottawa to examine the state of French-language education, to establish strong leadership for uniting the efforts of the whole community, and to stand together before public opinion. However, the 1910 convention was not the first patriotic congress held in Ontario — on 25 June 1883, members of the Sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Ontario met in Windsor.

During the final day of the Grand Congrès des Canadiens français de l’Ontario, delegates laid the groundwork for the first organization to defend the rights of the French-speaking minority in the province. The statues of the new organization specified that it was called the Association canadienne-française d’éducation de l’Ontario (ACFEO), that its mission was to claim all rights of French Canadians in Ontario and vigilantly oversee their interests, and that its members consisted of anyone who had French ancestry and lived in the province of Ontario.

The First Battle: French Education

The 1910 convention was an “education convention,” and the organization that emerged was an “education association.” Although delegates discussed education in the broader sense, bilingual schools were their main focus in 1910. This became the primary concern of the new education association for a number of years — and for good reason. On 25 June 1912, the Ontario government, led by James Pliny Whitney, announced the Circular of Instruction No. 17 regarding the language of instruction in bilingual schools. This regulation limited the use of French as the language of instruction and communication to the first two years of elementary school. The infamous Regulation 17 was the straw that broke the camel’s back for Franco-Ontarians. The ACFEO protested fervently and opposition formed overnight. It spread throughout the province and intensified year after year, peaking in 1916. The policy was relaxed, but it was not until 1927 that Regulation 17 was abandoned in response to the recommendations of the Scott-Merchant-Côté report. The regulation was in fact never officially repealed, but became obsolete in 1944, when it was not renewed in the statutes of the province of Ontario (see also Ontario Schools Question; Separate School).

Evolution of the Organization and its Priorities

Although the ACFEO was not a religious organization, president Ernest Désormeaux liked to state that there were 400,000 Franco-Ontarians (in 1940) who fought to preserve their faith by preserving their language. Ten years later, president Gaston Vincent made the most of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Dayto say that “Providence demands the total offering of our language, not so that we destroy it, but so that we use it in the glory of God.” This close relationship between Catholicism and the French language was fundamental to French Canadian nationalism at that time.

In 1969, under the presidency of Roger N. Séguin, the organization dropped éducation from its name and became simply the Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario (ACFO). It turned its attention to other issues, including the economy. In the early 1960s, Séguin was the organization’s first leader to address the matters of Franco-Ontarian purchasing power and savings control.

In the late 1970s, Franco-Ontarian leaders had a wide variety of concerns. Education continued to be a recurring issue — especially following various school crises that shook the province — as was the matter of services in French offered by the government of Ontario and Radio-Canada. In a speech given during the Rencontre des peuples francophones in Québec City in 1979, president Jeannine Séguin pointed out that northwest Ontario had no Radio-Canada radio or television services, and that the high assimilation rate in the area was therefore unsurprising (see Radio-Canada: Often the Only Voice of the Canadian Francophonie).

With Québec nationalismon the rise, French Canadians of the diaspora were sometimes forgotten, even disparaged. René Levesquedubbed francophones in Western Canada “dead ducks” during an episode of Twenty Million Questions on CBC in 1968, and novelist Yves Beaucheminspoke of “warm corpses” during the Bélanger-Campeau Commission on the future of Québec in 1990. Such remarks did nothing to ease tensions between Québécois and francophones outside Québec. During the 1980 Québec referendum, and again during the 1995 referendum, the ACFO did not campaign actively for the “No” side, but its federalist allegiance was well known. It felt that Québec was the bastion of Canadian Francophonie, and that French-language minority communities were its outposts. It supported a strong Québec in a united Canada.

Representation Today

In 2004, the Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario became the Association des communautés franco-ontariennes. Two years later, it changed its name to the Assemblée de la francophonie de l’Ontario (AFO) to adapt to a new reality in which francophones from Ontario were no longer a monolithic group. New immigrants now enriched the French-speaking community, and their arrival presented new challenges with respect to reception, support and integration.

Legacy and Challenges

Since the organization’s inception in 1910, the dynamic of French-speaking Ontario has constantly evolved. Furthermore, the demands of the AFO have changed and become more sophisticated over time. Franco-Ontarian leaders originally had a single preoccupation — access to education in French — but eventually widened the scope of their campaign to include other sectors such as justice and health. Although the battle over education continues in some degree, a range of programs and services are now offered in French to Ontario’s multicultural population.

See also Franco-Ontarian Flag; Bilingualism.

|

President |

Term |

|

Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt Charles-Siméon-Omer Boudreault Alphonse-Télesphore Charron Philippe Landry Napoléon-Antoine Belcourt Samuel Genest Léon-Calixte Raymond Paul-Émile Rochon Adélard Chartrand Ernest Désormeaux Gaston Vincent Aimé Arvisais Roger N. Séguin Ryan Paquette Omer Deslauriers Jean-Louis Boudreau Gisèle Richer Jeannine Séguin Yves Saint-Denis André Cloutier Serge Plouffe Jacques Marchand (interim) Rolande Faucher Jean Tanguay André J. Lalonde Tréva Cousineau Alcide Gour Jean-Marc Aubin Jean Poirier André Thibert (interim) Simon Lalande Mariette Carrier-Fraser Denis Vaillancourt |

1910–12 1912–14 1914–15 1915–19 1919–32 1932–33 1933–34 1934–38 1938–44 1944–53 1953–59 1959–63 1963–71 1971–72 1972–74 1974–76 1976–78 1978–80 1980–82 1982–84 1984–87 1987–88 1988–90 1990–94 1994–97 1997–99 1999–2000 2001–04 2004–05 2005 2005–06 2006–10 2010– |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom