The following article is an editorial written by The Canadian Encyclopedia staff. Editorials are not usually updated.

Brainy poetic iconoclast, mischievous punk and cultural court jester, Gord Downie flipped the script of Canadian identity and took us on a quest to discover ourselves.

“Interesting and sophisticated, refusing to be celebrated.”

— from “So Hard Done By” (Day for Night, 1994)

It has been said that Canadians don’t tell our own stories or celebrate our own myths. Our history is full of epics considered “too small to be tragic,” as The Tragically Hip’s Gord Downie once sang.

Or at least that’s what people used to say, before Downie and the Hip came along. Granted, there had long been singer-songwriters who specialized in telling Canada’s stories to Canadians. Stompin' Tom Connors. Stan Rogers. But they were largely perceived as cult figures whose unabashed Canadian-ness relegated them to the margins — quaint novelty acts in a society awash with American pop culture.

For decades, to be a “successful” English Canadian music artist meant you were successful in the United States, which typically meant conforming to the homogenized tastes of the mainstream American marketplace. The Tragically Hip changed all that. Their songs not only spotlighted Canadian stories, but did so in a unique, unconventional, often cryptic style that sounded like alien transmissions on US radio but still sold more albums in Canada than U2 or The Beatles.

“You’ll watch the border offer you fame and watch you drown.

I’m on the last American exit to the north land

I’m on the last American exit to my homeland.”

— from “Last American Exit” (The Tragically Hip, 1987)

Observers have always been somewhat perplexed by the Hip’s paradoxical appeal; that they are as beloved by high-minded intellectuals, who read Downie’s lyrics as literature on par with that of Al Purdy

, Margaret Atwood and Hugh MacLennan

, as they are by beer-swilling hosers who fist-pump their way through the band’s concerts, mouthing Downie’s cryptic lyrics every step of the way. But such is the nature of folk heroes. Be it Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen,

artists who become the voice of a generation express the collective consciousness with an eloquence and profundity that elevates it to the level of high art without losing touch with the grassroots.

And Downie was indeed the voice of a generation. My generation. Born into Pierre Trudeau’s nation-building exercise of the 1970s, I and so many other Gen Xers grew up with the distinct sense that Canada — English Canada, at least — was not a distinct society, but an ambivalent, amorphous, fragile culture with a tenuous grip on its own identity. As Northrop Frye once put it, Canadians were “conditioned from infancy to think of themselves as citizens of a country of uncertain identity, a confusing past, and a hazardous future,” whereas Americans were conditioned “to think of themselves as citizens of one of the world’s great powers.”

This was a dynamic that bred in most English Canadians an inherent inferiority complex, a somewhat resentful adulation of all things American, and a secret unrequited desire for us to matter as much as them. Most Canadians of my generation are familiar

with the rush of excitement that would come from hearing Canada or Canadians referenced in even the slightest way in American movies or television shows. It was as though we were the awkward, nerdy, anonymous outsider at high school who would get flustered

and speechless when the most popular kid in school asked us for the time.

“Me debunk an American myth?

And take my life in my hands?”

— from “At the Hundredth Meridian” (Fully Completely, 1992)

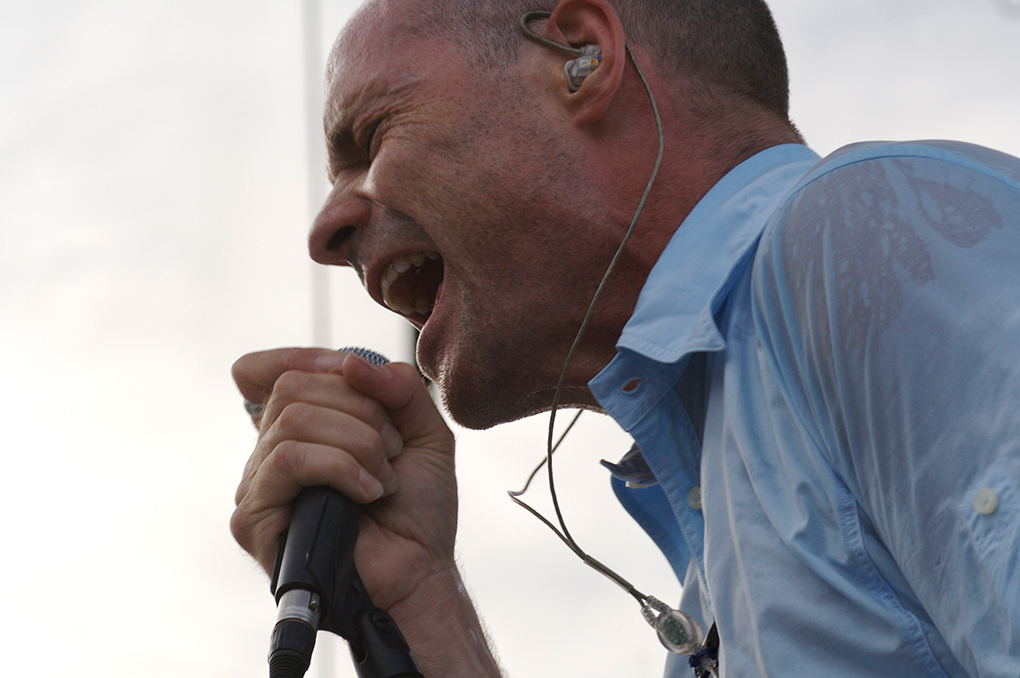

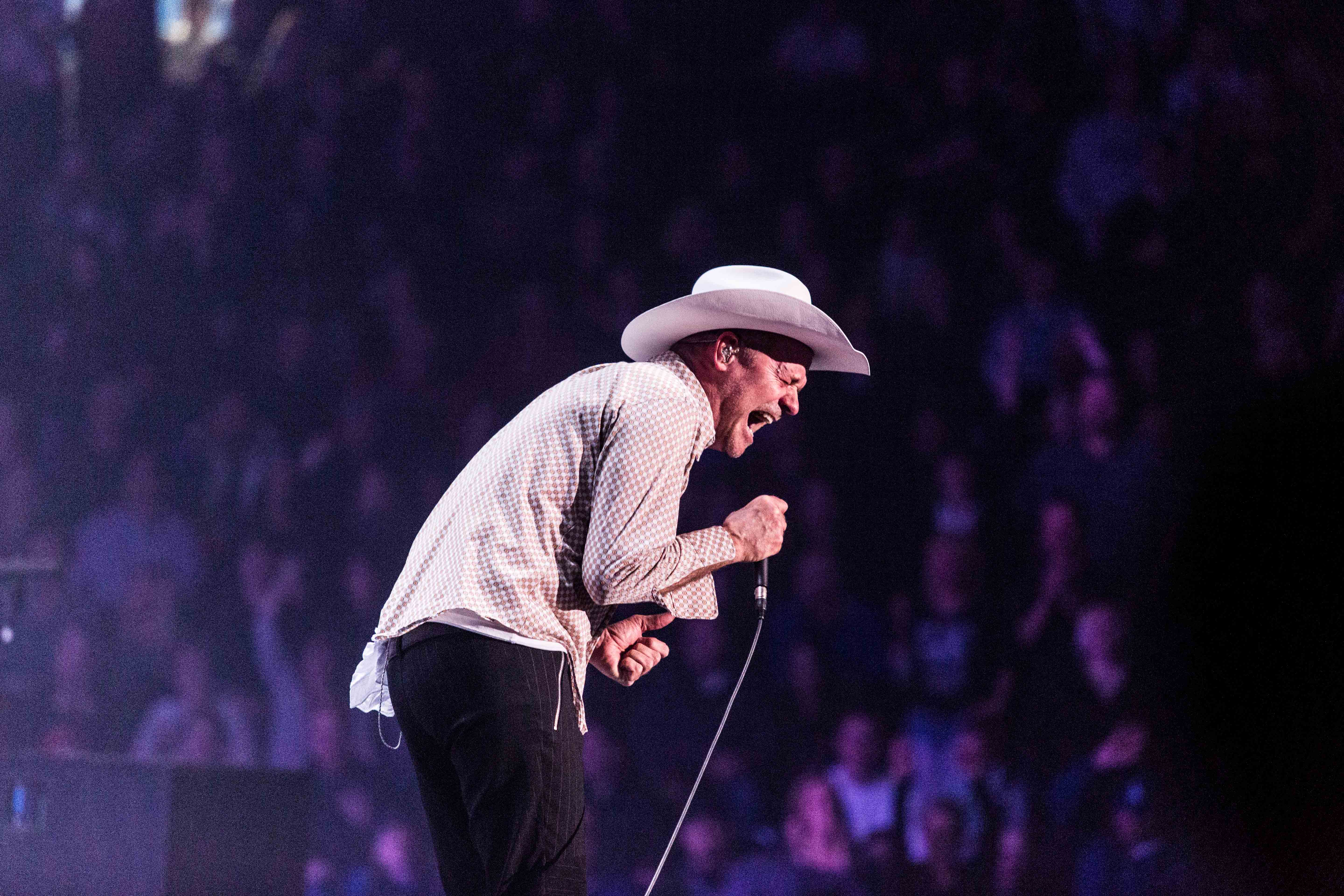

But Downie was like the innately confident, idiosyncratic art student who saw right through all that. Like a cross between Michael Stipe, Iggy Pop and the Fool from King Lear, he was equal parts brainy poetic iconoclast, mischievous punk and cultural court jester. He saw the genuinely cool kid beneath our pugly, insecure exterior and he was going to make us see it too, even if it meant dressing us up, taking us to prom and making a big awkward speech about how special we were in front of the whole school. And if the whole school didn’t respond with a rousing, spontaneous slow clap to show their approval, that was all right. In fact, it was better. Because, of course, being cool means not needing others to tell you you’re cool. “I can’t draw, but I can trace,” Downie sang on “Lionized,” from Fully Completely. “I know a lack you’ve got, and it makes a strong case for art.”

The fact that the Hip never broke through in the United States, despite their massive, unprecedented popularity in Canada, meant that we were celebrating ourselves — not just our own artists and stories, but our own distinct way of telling those stories. There was nothing overtly Canadian about the work of, say, Joni Mitchell, Anne Murray, Rush, Bryan Adams, Alanis Morisette or Shania Twain. But they were Canadians succeeding on the world stage, and so we felt proud of them. But the magic of Downie and the Hip is that they made us feel proud of ourselves. The Morisettes and the Twains that we’ve produced belong to the world. But the Hip belong to us, and we to them.

“Isn’t it amazing what you can accomplish

when you don’t let the nation get in your way

No ambition whisperin’ over your shoulder

Isn’t it amazing you can do anything.”

— from “Fireworks” (Phantom Power, 1998)

Downie’s most significant accomplishment was to completely reconceptualize Canadian identity, which for generations had been characterized by the central question posed by Northrop Frye: “Where is here?” In other words: What is our place and role in the world? Where do we fit in relation to the greater powers around us? How do we locate our significance in a world where everything that really matters happens elsewhere?

Instead of asking “Where is here?” Downie dispensed with the uncertainty and doubt — and most importantly the sense that Canada’s proper place was in the periphery — and declared “Here is where.” He took what had been a question and turned it into a quest.

Placing us front and centre, he set out to discover and express an authentic sense of identity and belonging. Along the way, he taught us that our perceived weakness was one of our greatest strengths; that our absence and amorphousness, our lack of any

real concrete identity, was not only an essential part of our identity, but a defining characteristic that could be immensely empowering.

Gord Downie helped us feel confident in being Canadian, and encouraged us to see that we were super cool just the way we were. No matter what anyone else thought.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom