Early Life

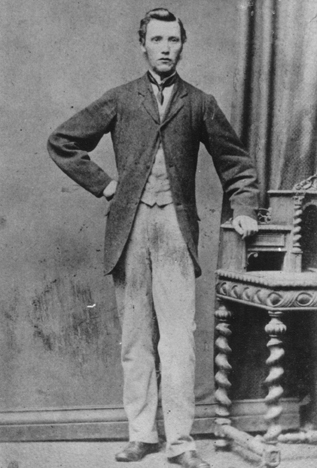

Thomas Scott was born in Clandeboye, County Down, near Belfast, Ireland. His parents were Protestant farmers. In 1863, at age 21, he joined a wave of people leaving Ireland. He arrived in Canada West, what is now Ontario, and settled near Belleville. Scott worked as a labourer and was a member of the Hastings Rifles. He also joined the powerful, anti-Catholic Orange Order.

Red River

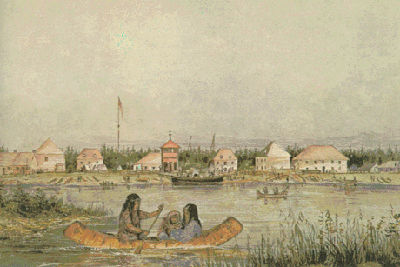

Scott eventually travelled west, looking for better opportunities. In the spring of 1869, he arrived at the Red River Colony, at the forks of the Assiniboine and Red rivers (see The Forks). It was home to about 5,000 descendants of French explorers and fur traders who had married Indigenous women (see Voyageur). Most Métis were Catholic and French-speaking, but a large minority were English-speaking Protestants. A growing number of Protestant, English-speaking Canadians, like Scott, were also moving to Red River.

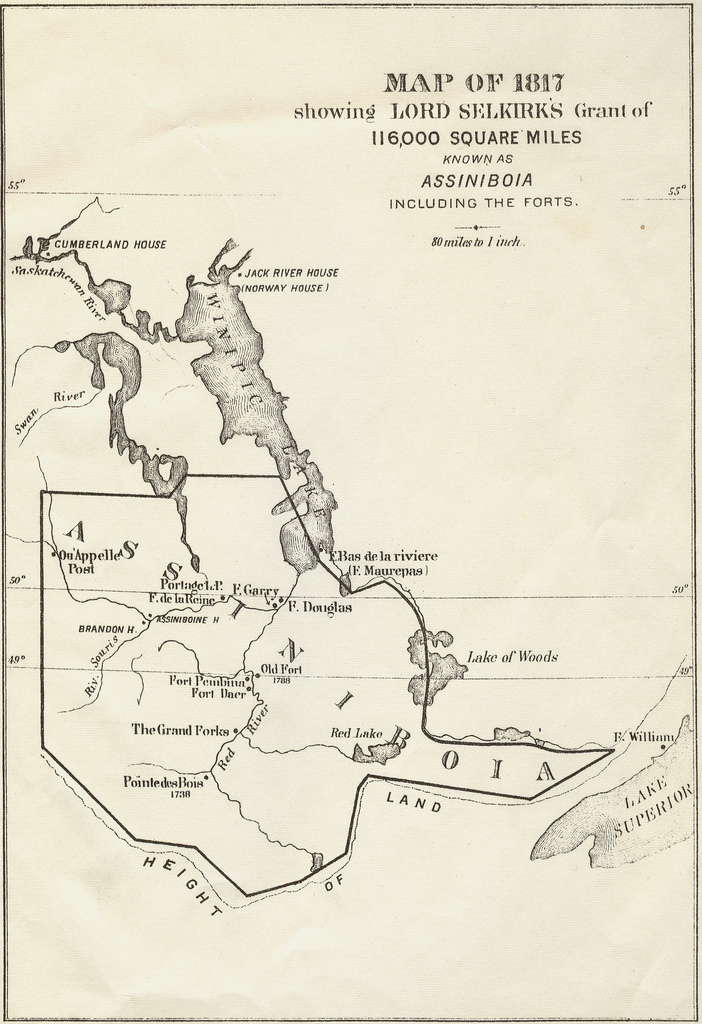

Red River was part of an vast region called Rupert’s Land that had been owned by the Hudson Bay Company. In March 1869, just before Scott’s arrival, it had been sold to the British crown with the intent to sell it to the Dominion of Canada. The Canadian purchase would not be official until 1 December.

Between March and December 1869, people were confused about who owned the land and governed its people. This added to the resentment among people at Red River who had not been consulted about the sale. Racial, religious, and ethnic tensions were made worse by the belief that the sale would bring even more Protestant migrants from Ontario.

The settlement was also split because some people wanted to join Canada, others wanted the colony to be independent, others hoped that Red River would become a British colony, and still others wanted to join the United States.

When he arrived in Red River, Scott joined a construction crew building the Dawson Road between Red River and Fort William. In August, it was discovered that the project’s superintendent and paymaster, John A. Snow, had been underpaying the workers. Scott led a gang that dragged Snow to the river and threatened to throw him in. In November, Scott was charged with assault, fined £4 and fired.

Scott found work as a labourer and bartender. According to some writers and historians, Scott was known at this point for fighting, drinking and shouting his anti-Catholic and anti-Métis views. By other accounts, he was quiet and did not offend others.

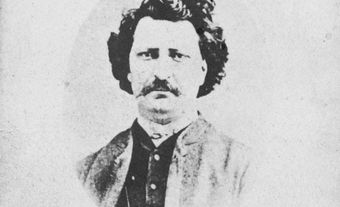

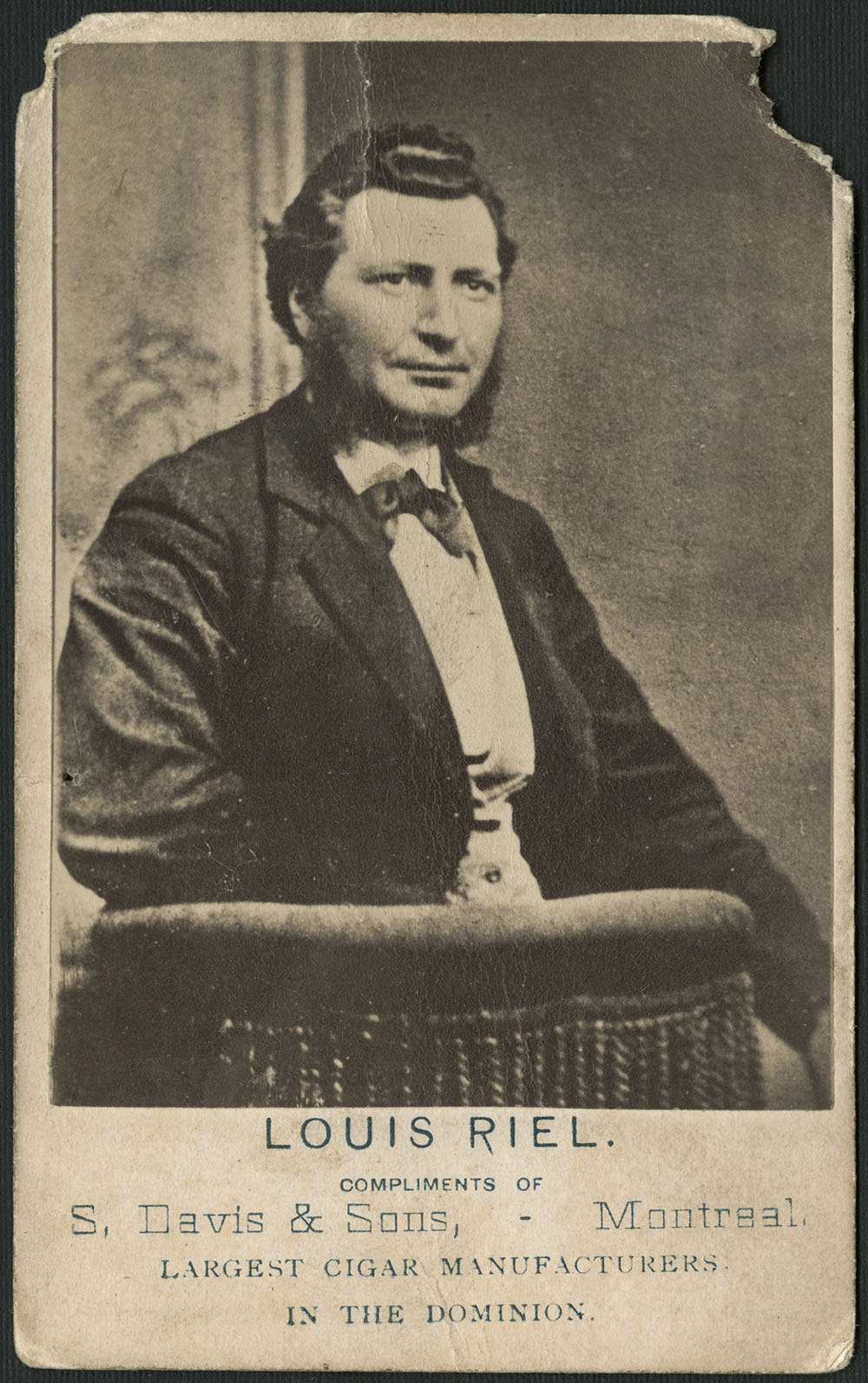

While Scott was working on the Dawson Road, a Canadian survey crew had arrived near Red River. The Métis insisted that until the 1 December ownership transfer, the crew had no official status and was trespassing. The Métis spokesperson was Louis Riel, who had just come home from Montreal, where he had studied to become a priest. Supported by armed men, Riel dramatically placed his foot on the surveying chain and ordered the crew to leave.

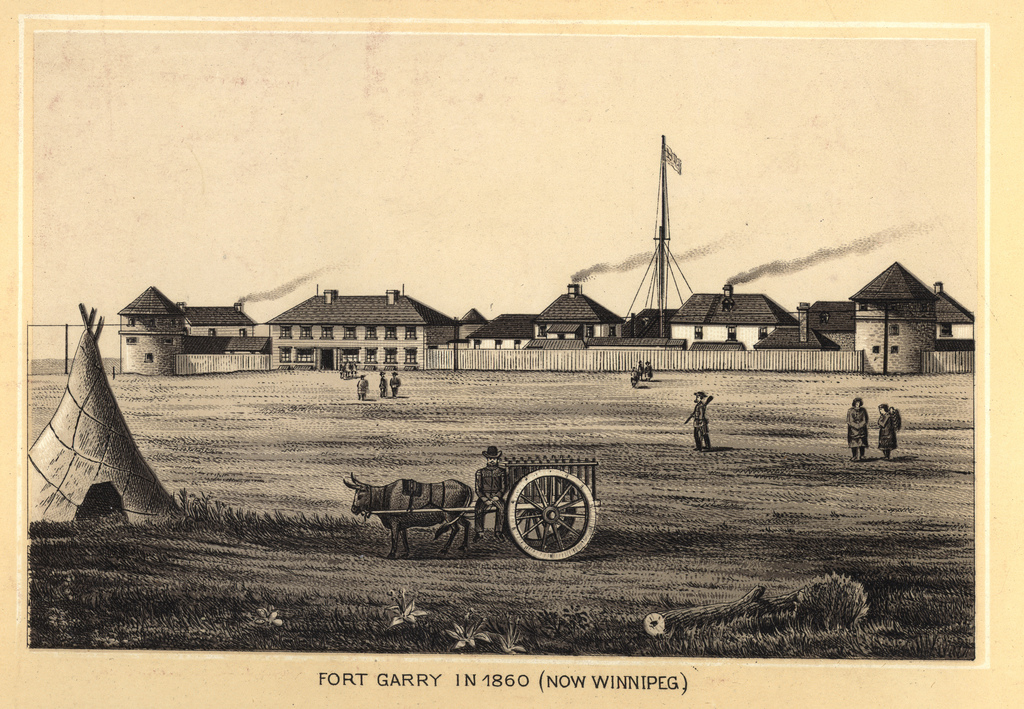

The Métis took over Upper Fort Garry, the Hudson Bay Company’s post in Red River, and formed a provisional government called the Métis National Committee. Riel was its secretary.

Meanwhile, Scott had met the 29-year-old doctor and entrepreneur John Christian Shultz. Shultz led the Canadian Party, a small group of English Protestants who wanted Red River to be taken over by Canada and led by English Protestants. In early December, 67 Canadian Party followers gathered at Shultz’s warehouse in Lower Fort Garry to plan an attack on the Métis government.

The Métis founded the Provisional Government of the Métis Nation with Riel as president. On 7 December, Riel had Shultz and his followers arrested and detained. Scott had not been at the warehouse but when he learned about the arrests he demanded that the prisoners be freed. When Riel refused, Scott yelled racist insults, and so was arrested. He continued his tirades while imprisoned, threatening at one point to shoot Riel.

On 9 January, Scott and 12 other men escaped. He and Charles Mair found snow shoes and somehow walked 103 km through a blizzard to Portage la Prairie. A month later, still suffering from frostbite, Scott joined Canadian Major Charles Arkoll Boulton and about 60 others who marched through cold and snow, intent on capturing Upper Fort Garry, freeing the prisoners, and overthrowing Riel. They were joined along the way by another 100 men armed with muskets and clubs.

\

When they arrived, they learned that Riel had already released the prisoners. While the news led many to turn back, Boulton, Scott and 45 others continued to insist that Riel step down. Riel had them arrested.

A military council determined that Boulton was guilty of treason and should be executed. After appeals from church leaders and Donald Smith, the commissioner from Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald’s government, Riel dropped the sentence. The incident, and Riel’s mercy, improved support for the provisional government in Red River.

Execution of Thomas Scott

Meanwhile, Thomas Scott remained in jail, where he become a nuisance. He complained about conditions and constantly shouted violent threats and racist insults at his Métis guards. They chained his feet and hands, but he kept on. On 28 February, after hitting a guard, two other guards dragged Scott outside and beat him until a member of Riel’s government stopped them. Riel visited Scott and, speaking through a hole in the door, tried to calm the man but Scott shouted more insults.

On 3 March, Scott was charged with insubordination and treason by a six-man council. He was not allowed a lawyer and, because he did not speak French, he did not understand the evidence against him. Witnesses were not cross-examined. At the end of the trial, Riel addressed Scott in Englishand summarized what had happened. One member of the council voted for acquittal and another for banishment. Four declared Scott guilty and said he should be executed by firing squad (see Capital Punishment).

A minister, a priest, and Donald Smith asked Riel to spare Scott’s life, but he refused. Riel believed that the trial and Scott’s execution would demonstrate the power of his government to the people of Red River and, as he said to Smith, “We must make Canada respect us.”

At one o’clock on 4 March 1870, Scott’s hands were tied behind his back and he was escorted from his cell to the courtyard outside. With Riel watching, Scott knelt in the snow, and a white cloth was tied to cover his eyes. Scott shouted, “This is horrible. This is cold-blooded murder.” Six Métis men raised their muskets, but when the order to fire came, only a few shots rang out. Scott was hit twice and crumpled to the ground but was still alive. François Guillemette, a member of the firing squad, stepped forward, withdrew his revolver, and ended Scott’s life.

Significance of Scott’s Death

The controversy around Scott’s execution did not change Macdonald’s mind about Manitoba. But to ease Ontario’s anger, he sent 1,200 soldiers and militiamen to Red River (see Red River Expedition). By the time they arrived in August, Riel had fled to the United States.

Prime Minister Macdonald welcomed representatives from Red River to negotiate. He agreed with most of Riel’s terms, including: the creation of the province of Manitoba; guaranteed protection for Métis land, the Catholic religion, and French language; and that treaties be negotiated with Indigenous nations. Manitoba entered Confederation in July 1870.

French-speaking Quebecers supported Riel for protecting French-Catholic rights. But after Scott’s execution, many people in Ontario demanded that Riel be arrested for Scott’s murder. They were influenced by propaganda spread by Shultz, who had returned to Ontario and was supported by the Orange Order.

Riel’s part in Scott’s execution destroyed his ability to participate in Canadian politics. Riel was elected as the Member of Parliament for Provencher three times between 1873 and 1874. However, Ontario Orangemen had a $5,000 reward on Riel’s head for the murder of Thomas Scott. Because Riel feared arrest or even assassination, he did not take his seat in the House of Commons.

Riel returned from exile in the United States and in 1885 led Saskatchewan’s Métis in the North-West Resistance. This caused Ontario Protestants to demand Riel’s arrest again. When the resistance was stopped, Riel was arrested and charged with high treason. Scott’s execution played a significant part Riel’s trial and death sentence. It was also part of the reason why Macdonald allowed the death sentence to be carried out.

There are still rumours about what happened to Scott’s body. Some claim it was thrown into the river and others that it was buried in an unmarked grave or under a building. It has never been found.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom