This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Notable Films and Filmmakers 1980 to Present.

Pioneering Years, 1896–1914

The American film industry can be dated back to 1903. This was when narrative filmmaking (The Great Train Robbery, Uncle Tom’s Cabin) and the world’s first movie studio to rely entirely on artificial light (in New York City) were introduced. But it is almost impossible to speak of a Canadian film industry at the birth of cinema.

The first public screening of a film in Canada took place in Montreal on 28 June 1896. Two years earlier, Andrew and George Holland of Ottawa had opened the world’s first Kinetoscope parlour in New York City featuring Thomas Edison’s latest invention. In July 1896, the Holland brothers introduced Edison’s Vitascope to the Canadian public in Ottawa’s West End Park. Among the scenes shown was The Kiss, starring May Irwin, a Broadway actress from Whitby, Ontario. On 31 August, the first screening in Toronto took place at Robinson’s Musée on Yonge Street. The first screening in Vancouver was in December 1898.

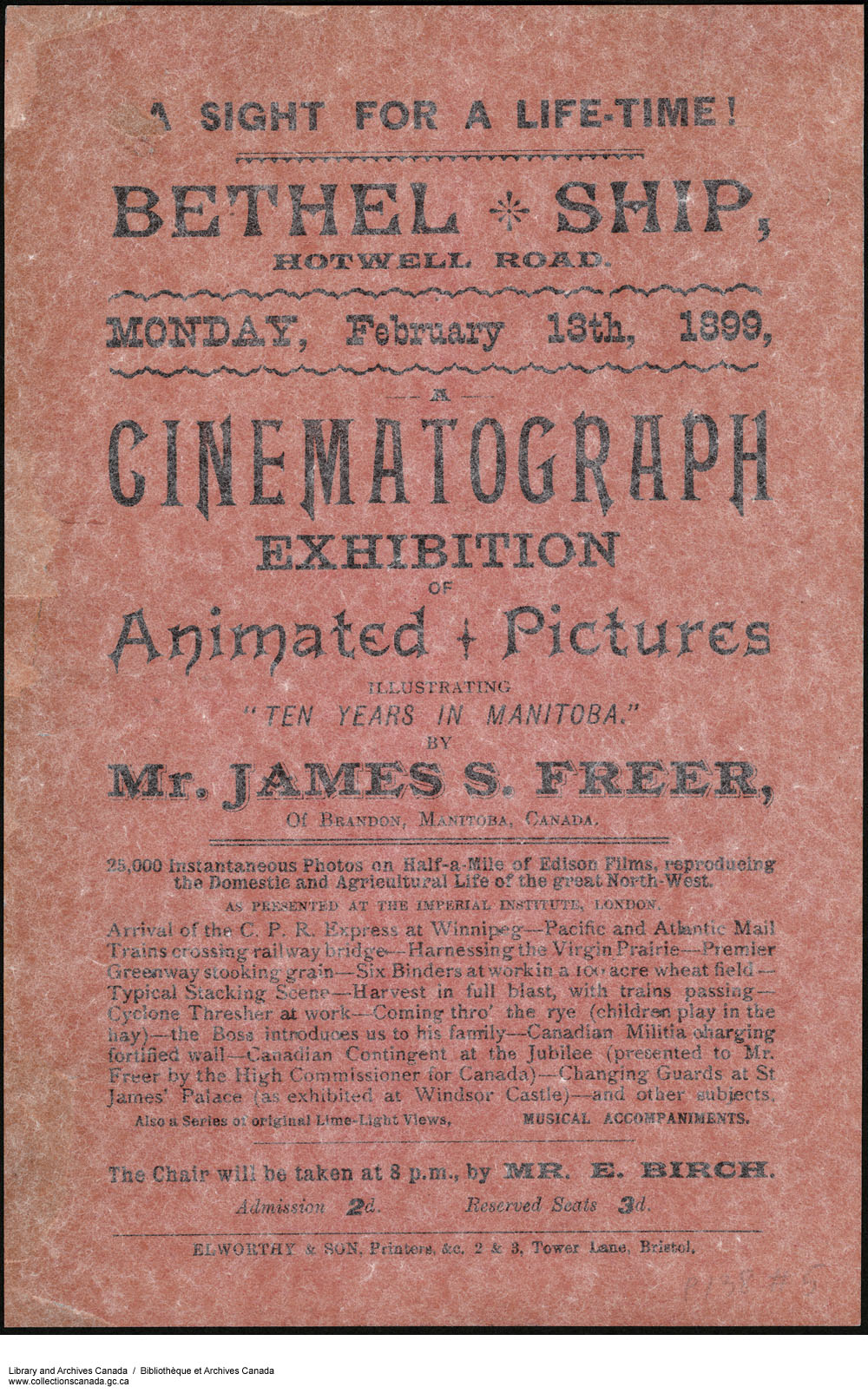

The first Canadian films were produced in the fall of 1897, a year after the Montreal debut. They were made by James Freer, a Manitoba farmer, and depicted life on the Prairies. Some of his films were Arrival of CPR Express at Winnipeg, Pacific and Atlantic Mail Trains and Six Binders at Work in a Hundred Acre Wheatfield. In 1898, sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Freer toured England with his “home movies.” They were collectively entitled Ten Years in Manitoba. They were so successful that the federal government sponsored a second tour by Freer in 1902.

That same year, the CPR hired a British company to bring together a group of filmmakers, known as the Bioscope Company of Canada, to produce Living Canada. This series of 35 scenes depicting Canadian life was designed to encourage British immigration to Canada. The series included the first fictional drama made in Canada, the 15-minute-long Hiawatha, The Messiah of the Ojibway (1903). Also in 1903, Léo-Ernest Ouimet established Canada’s first film exchange in Montreal. He opened the first theatre in Montreal in 1906, followed in 1907 by the largest (1,200 seats) luxury theatre in North America. It was also in Montreal.

The CPR continued to produce films promoting immigration into the 1930s. In 1910, it hired the Edison Company to produce 13 story films to dramatize the special virtues of settling in the Canadian West. (See also: History of Settlement in the Canadian Prairies.) These promotional films were characteristic of most Canadian productions through 1912. They were financed by Canadians but made by non-Canadians. Their objective was to sell Canada or Canadian products abroad. The few Canadians who produced their own films (such as Ouimet in Montreal, Henry Winter in Newfoundland and James Scott in Toronto) made only newsreels or travelogues. Meanwhile, American film companies were beginning to use Canada as the setting for narrative films. Many of them featured villainous French Canadian lumberjacks, Métis, gold prospectors and noble Mounties.

After 1912, film companies in several Canadian cities began producing fiction as well as factual films. In Halifax, the Canadian Bioscope Company made the first Canadian feature, Evangeline (1913). It was based on the Longfellow poem about the expulsion of the Acadians. It was a critical and financial success. The company made several other less successful films before folding in 1915. The British American Film Company of Montreal, one of several short-lived companies in that city, produced The Battle of the Long Sault (1913). In Toronto, the Conness Till Film Company made several comedy and adventure films in 1914 and 1915. In Windsor, Ontario, the All Red Feature Company produced The War Pigeon (1914), a drama about the War of 1812.

Early Government Censors and Film Boards

From the beginning, the regulation of film content, distribution and exhibition was a provincial matter. Each province set its own standards and practices. In 1911, Ontario established the first Board of Censors in North America and Manitoba passed an act that delegated film censorship to the City of Winnipeg. Ontario’s board was considered the gold standard across North American jurisdictions. British Columbia, Alberta and Quebec established active censor boards in 1913. Manitoba created a proper provincial board in 1916.

The Ontario Motion Picture Bureau (OMPB) was the first state-sponsored film organization in the world. It was founded in May 1917 to provide “educational work for farmers, school children, factory workers and other classes.” Its mandate was to produce films that would advertise Ontario and promote infrastructure projects. The OMPB initially contracted all production to private companies in Toronto. In 1923, it purchased the Trenton Studios and began making its own films. (The first movie studio in Canada, the Trenton Studios opened as Adanac Films in Trenton, Ontario, in 1917.)

At its peak in 1925, the OMPB distributed 1,500 reels of film per month. It used 28mm, non-theatrical safety stock in order to avoid the fire hazard posed by 35mm nitrate stock. Its distribution system became outdated in the late 1920s when 16mm film stock replaced 28mm. After becoming inefficient and irrelevant, the OMPB was shut down in October 1934. However, it established a legacy of government involvement in Canadian filmmaking that would become a defining feature of the Canadian film industry.

The Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau was founded as the Exhibits and Publicity Bureau in 1918. It was the first national film production unit in the world. Its purpose was to produce films that promoted Canadian trade and industry. As the minister of Trade and Commerce put it in 1924, the Bureau “was established for the purpose of advertising abroad Canada’s scenic attractions, agricultural resources and industrial development.”

The Bureau produced a series of theatrical short films called Seeing Canada. It distributed the series theatrically in Canada and abroad. By 1920, the Bureau maintained the largest studio and post-production facility in Canada. It also distributed its films to numerous countries around the world. But for all its successes in production and distribution, the Bureau never attempted to develop a domestic film production industry in Canada. In fact, it actively discouraged it. Instead, it favoured a business model that saw Canada as a branch plant of the American industry. (See also: Staple Thesis.) Bernard E. Norrish, the Bureau’s first director, stated that Canada “had no more use for a large moving picture studio than Hollywood had for a pulp mill.”

The Bureau focused on travelogues and industrial films through the 1920s and 1930s. It made sporadic attempts at more meaningful projects, such as Lest We Forget (1935) and The Royal Visit (1939). However, the Bureau didn’t convert to sound films until 1934. It was effectively replaced in 1939 by the creation of the National Film Board (NFB). The NFB officially absorbed the Bureau in 1941.

Expansion and Production, 1917–1923

The growth of Canadian nationalism around the First World War resulted in a brief flurry in Canadian production and other aspects of the film industry. The first widely released Canadian newsreels appeared. Feature film production also expanded, as did the Canadian-owned Allen Theatres chain and associated distribution companies. The motion picture bureaus established by the Ontario government in 1917, and the federal government in 1918, also contributed to the boom in activity.

This optimistic period of expansion was led by a number of enterprising producers. George Brownridge was principal promoter of Canada’s first film studio, Adanac Films (opened in Trenton, Ontario, in 1917). He produced three feature films, including the anti-Communist The Great Shadow (1919). Léo-Ernest Ouimet was a producer, exhibitor and distributor who established the country’s first film exchange in 1903. He also opened Canada’s first luxury theatre in Montreal in 1907. Blaine Irish was head of Filmcraft Industries. He produced the feature Satan’s Paradise (1922) and two successful theatrical short film series. Bernard Norrish was the first head of the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau. He was later head of Associated Screen News (ASN). Charles and Len Roos were producers, directors and cameramen of many films, including the feature Self Defence (1916). And finally, A.D. “Cowboy” Kean was an early cameraman and producer.

However, the most successful Canadian producer of this period was Ernest Shipman. He had already established his reputation as a promoter in the US. He returned to Canada in 1919 with his author/actress wife, Nell Shipman, to produce Back to God’s Country (1919) in Calgary. This romantic adventure about an embattled heroine triumphing over villainy was released worldwide. It returned a 300 per cent profit to its Calgary backers, due in no small part to Nell’s groundbreaking nude appearance in the movie.

During the next three years, Ernest Shipman established companies in several Canadian cities. He made a number of features based on Canadian novels. All of them were filmed not in studios, as was the common practice at the time, but on location. These films — including God's Crucible (1920), Cameron of the Royal Mounted (1921), The Man from Gelngarry (1922) and The Rapids (1922) — were not as profitable as his first, but they were not failures either. Only his last film, Blue Water (1923) — made in New Brunswick with future Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) star Norma Shearer — was a disaster. Shipman left Canada in 1923 and died in 1931 in relative obscurity.

Ernest Shipman’s departure also marked the end of the minor boom in Canadian production. In 1923, only two feature films were produced in Canada, compared to nine in 1922. Even the production of short films showed a sharp decline. However, the number of Hollywood films with Canadian plots increased markedly.

Through the rest of the 1920s, production in Canada mainly consisted of inserts for American newsreels, sponsored short films, and documentaries produced by the government motion picture bureaus and a handful of private companies. There was one brief resurgence in 1927. Private investors contributed $500,000 to produce Carry on Sergeant!, a silent drama about Canadians in the First World War. It was written and directed by British author and cartoonist Bruce Bairnsfather. Though well received by critics, it came at the dawn of the sound era and died within weeks of its release.

The CMPDA and Famous Players, 1922 Takeover

Theatre ownership has traditionally been the most lucrative sector of the film industry. The theatre owner would typically take 50 per cent of every ticket sold. Because of the high cost of film production, widespread distribution is vital to a film’s commercial success. In the 1920s, the major Hollywood studios (Paramount, RKO, 20th Century Fox, MGM and Warner Bros.) adopted a vertically integrated model of ownership. This allowed them to combine production and distribution under one umbrella. The majors then aligned themselves with the large national theatre chains to guarantee an outlet for their product. In some cases, they purchased theatre chains outright.

In 1924, the Motion Picture Exhibitors and Distributors of Canada (MPEDC) was formed. (It became the Canadian Motion Picture Distributors Association, or CMPDA, in 1940. Since 2011, it has been called the Motion Picture Association – Canada.) Although Canadian in name, the association consisted of the Canadian offices of the major American distribution companies. It was essentially a branch of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association of America. For the purposes of calculating domestic gross revenue, American distributors began including Canada in their bottom line.

In 1923, American-born N.L. Nathanson, owner of the Toronto-based Famous Players Canadian Corporation (FPCC), bought all 53 of the Canadian-owned Allen Theatres. This made Famous Players the largest theatre owner in Canada and gave it control of the Canadian exhibition market. However, FPCC was owned by Adolf Zukor’s Paramount Pictures. Zukor, through his holding company, thus seized direct control of the exhibition market in Canada.

In 1930, under the Federal Combines Investigation Act, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett appointed Peter White to investigate more than 100 complaints against American film interests operating in Canada. White’s report concluded that Famous Players was a combine “detrimental to the Public Interest.” The provinces of Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and BC took FPCC and the American distribution cartel represented by the CMPDA to court in Ontario. After a lengthy trial, FPCC and other defendants were found not guilty on three counts of “conspiracy and combination.”

A decision against the US cartel would have been a historic turning point for the future of filmmaking in Canada. Films were still produced by Associated Screen News and government agencies. However, these suffered funding cutbacks during the Great Depression. By the 1930s, the Canadian film industry became virtually a branch plant of Hollywood.

“Quota Quickies”

European film industries also faced the threat of Hollywood domination in the 1920s. But most governments there moved quickly to protect their domestic industries. They typically controlled the ownership of exhibition and distribution companies, or stimulated national production. Canada took no comparable action.

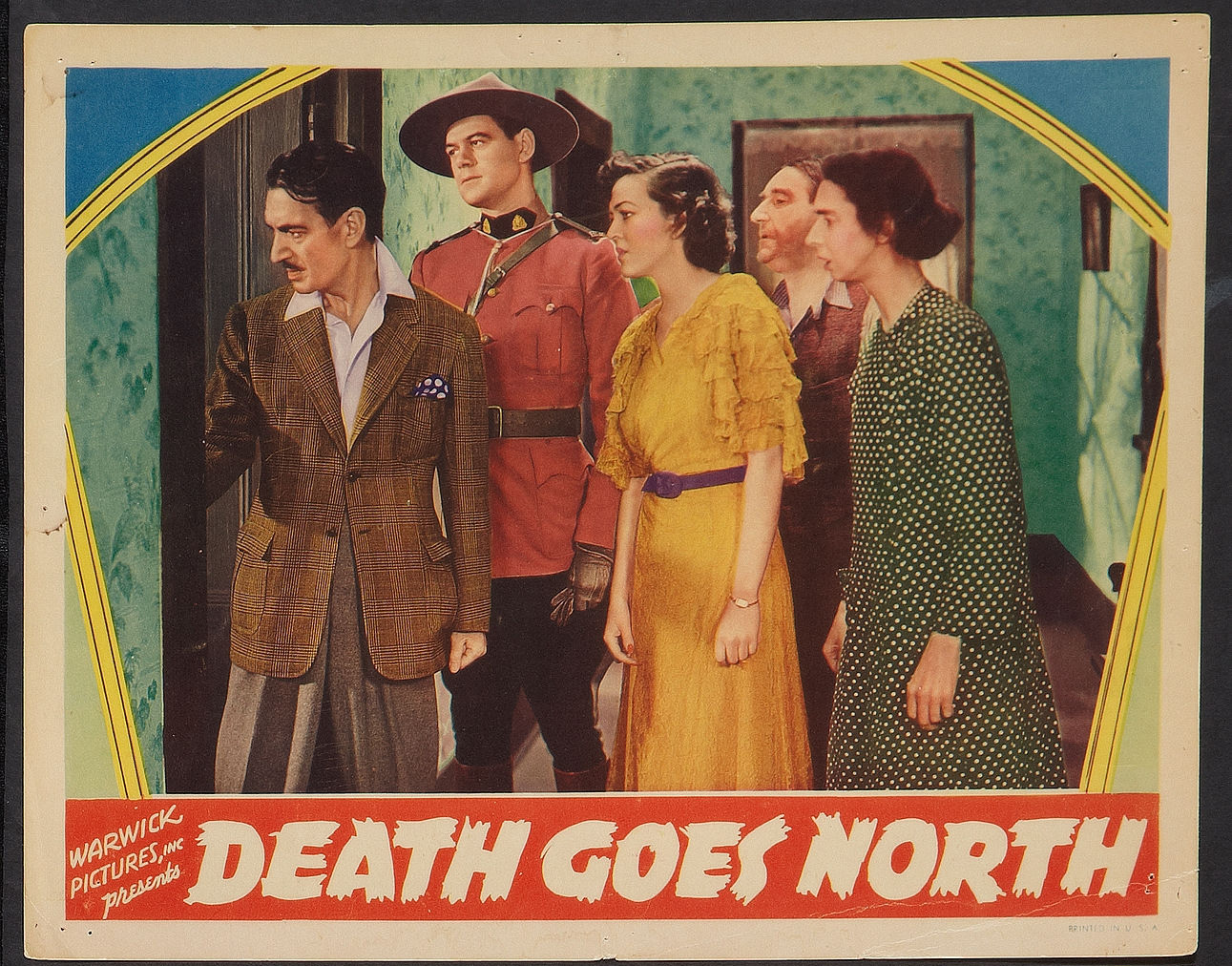

One such action was taken by the United Kingdom. It passed the Cinematographic Films Act of 1927, which came into effect in 1928. The law stipulated that 15 per cent of films shown in Britain had to be of British or Commonwealth origin. From 1928 to 1937, a total of 22 low-budget feature films were produced in Canada by Canadian-based, American-financed companies in order to take advantage of the quota. These films were commonly referred to as “quota quickies.”

When the legislation was introduced, production companies sprang up in Calgary, Montreal and Toronto. The most active producer of quota quickies was Kenneth Bishop of Victoria, BC. He produced two films (1932–34) through his Commonwealth Productions and another 12 films in three years (1935–37) through his second company, Central Films. Only some of the films were set in Canada. All of them were essentially generic Hollywood B-movies. Bishop had all the post-production and editing done in Hollywood. This allowed his financiers, Columbia Pictures, to approve the final product.

The quota law was renewed by the British government in 1938. It was amended to remove the inclusion of Commonwealth films. This was mainly due to the way Canada had allowed the law to be subverted. There were attempts in Ontario, Quebec and Alberta to introduce provincial quotas for British films. None of these bills became law.

In his book One Hundred Years of Canadian Cinema, George Melnyk argued that the quota quickies “played their own historical role in marking Canada’s transition from its British colonial past to its new imperial master, the United States.” As Lewis Selznick, one of Hollywood's pioneering producers, once remarked, “If Canadian stories are worth making into films, American companies will be sent into Canada to make them.”

Years of Inaction

The only memorable Canadian feature of this period was The Viking (1931). It depicted the hazardous life of Newfoundland’s seal hunters. It was produced in Newfoundland between 1930 and 1931 by American adventurer Varick Frissell. It is technically not a Canadian production. But it is a key example of what was to become a characteristic Canadian genre — documentary dramas. These films blend fiction and nonfiction, are rich in a sense of place, and explore the relationship between people and their environment. This approach emerged early in Canadian film and distinguished many later Canadian features.

In the 1930s, however, this docudrama approach was scarcely evident. The commercial industry had died, the Ontario Motion Picture Bureau had been closed down by the provincial Liberals, and the studio in Trenton was closed. Even the Government Motion Picture Bureau had lapsed into sterility. Only in the work of a few individuals (especially Bill Oliver in Alberta, and Albert Tessier and Maurice Proulx in Quebec) and at Associated Screen News (founded in Montreal in 1920 and active until 1958) was there any continuing sense of creative vitality. ASN mainly produced newsreels and sponsored films. But it did produce two widely released short-film series: Kinograms in the 1920s; and the Canadian Cameo series from 1932 to 1953. Supervised and usually directed by Gordon Sparling, these films showed flair and imagination. They were almost the only film representation of Canada at home or abroad during this period.

Only one English Canadian feature film was made in the 1940s — Bush Pilot (1946), an imitation of Hollywood’s Captains of the Clouds (1942). A print of the film was restored by the National Archives (now Library and Archives Canada) and TMN television network.

This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Notable Films and Filmmakers 1980 to Present.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History; Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation; Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time; English Canadian Films: Why No One Sees Them; National Film Board of Canada; Telefilm Canada; Canadian Feature Films; Film Education; Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Film Cooperatives; Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom