Early Life and Education

Stephen Leacock was born in Swanmore, England, the third of eleven children to Peter Leacock and Agnes Butler. When he was six, his family emigrated from England to Canada and settled on a hundred acre farm near Lake Simcoe, Ontario. In 1878, his father abandoned the family, leaving his mother to tend to eleven children.

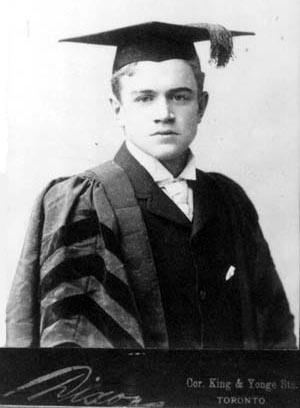

Stephen Leacock began his education locally and later attended Upper Canada College in Toronto. In 1887, he enrolled at the University of Toronto, where he studied modern and classical languages and literature. He excelled as a student and graduated from University College in 1891 with a Bachelor of Arts degree with high honours in Modern Languages.

In the 1890s, Leacock began publishing humour pieces, which appeared in publications such as Truth and Life in New York City and Grip magazine in Toronto. Although he was developing a reputation as a great wit, Leacock’s central ambitions were still in the field of academics. In 1899, he was accepted into a PhD program at the University of Chicago. He studied economics and political science under the political scientist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, who coined the phrase “conspicuous consumption” in his influential book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).

In 1899, Leacock married the actress Beatrix Hamilton. They had one son, Stephen Lushington Leacock, who was born in 1915.

In his third year at the University of Chicago, Leacock joined McGill University as a special lecturer in political science and history. In 1903, he completed his doctoral dissertation, The Doctrine of Laissez-Faire, and was granted his PhD magna cum laude. That same year, he took a job as a full-time assistant professor at McGill’s Department of Economics and Political Science. He rose quickly to become department head, where he remained until his mandatory retirement in 1936.

Stephen Leacock's high school graduation picture from Upper Canada College, 1887.

Mid-career

A prolific writer of humorous fiction, literary essays and articles on social issues, politics, economics, science and history, Leacock claimed near the end of his life, “I can write up anything now at a hundred yards.” Most of his books are collections of these works, originally written for magazines.

This was not the case for his first book, Elements of Political Science (1906), a workmanlike treatment of its subject. Although he was not an original or particularly incisive political economist, Leacock’s professional opinions on matters such as the need for a gold standard have proved prophetic in their common sense approach to what he considered a jungle of statistics. Elements of Political Science became a widely read university textbook for 20 years after its publication. It was Leacock’s best-selling book in his lifetime.

Leacock’s writings on the theoretical and technical aspects of humour are similarly refreshing for their accessibility, as are his views on education. He was politically active in the Conservative Party in both his home riding in Orillia, Ontario, and nationally. In the 1911 general election, his writings and public addresses on the issue of reciprocity helped defeat Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government. Although Leacock was a man of many seeming contradictions, generally his stance was traditionally conservative. An old-school Tory, he valued the community over the individual, organic growth over radical change, and the middle way over extreme deviation. Such values form the basis of Leacock’s satiric norm, the authorial position from which he attacked rampant individualism, materialism and worship of technology. Although frequently unfaithful to his credo that humour be kindly — he was at times racist, anti- feminist and downright ornery — the unique combination of compassion and caustic wit remain the elements which accord his humour a timelessness few Canadian writers have achieved.

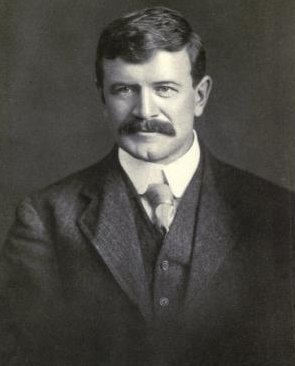

Stephen Leacock in 1913.

Notable Works

Stephen Leacock’s two masterpieces are Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912) and Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (1914). The first humorously anatomizes business, social life, religion, romance and politics in the typical, small Canadian town of Mariposa. Perhaps the greatest creation of Sunshine Sketches is the narrator himself, who, in his affection for and bemusement at the community of Mariposa, reveals the essential Leacock.

Arcadian Adventures dissects life in an American city with sharper satire, less qualified by the author’s affection and pathos. Taken together, these two books reveal the imaginative range of Leacock's vision — the nostalgic concern for what is being lost with the passing of human communities and his fear for what may ensue. However, Leacock also believed that the best humour resides at the highest reaches of literature.

Later Career

Leacock maintained a prolific career in writing, teaching and public life. He was a founding member of The Canadian Author’s Association in 1921. In 1925, Leacock’s wife died of breast cancer, which prompted him to become a vocal proponent and fundraiser for breast cancer research and awareness (Leacock died of throat cancer in 1944 ). In 1928, he moved to Old Brewery Bay in Orillia, Ontario, where he built a house. It was later converted into a museum and was declared a National Historic Site in 1992.

Honours and Legacy

Leacock was elected to the Royal Society of Canada in 1919 and won the prestigious Mark Twain Medal for humour in 1935. He was awarded the Lorne Pierce Medal from the Royal Society of Canada in 1937 for his contributions to Canadian literature, and received the Governor General’s Literary Award for non-fiction for My Discovery of the West (1937) in 1938.

The Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour was established in his honour in 1947. It awards an annual cash prize to the best humorous book by a Canadian author, selected by a jury. Winners of the award have included Patrick deWitt, Will Ferguson, Stuart McLean and Mordecai Richler. In 1968, Stephen Leacock was designated a National Historic Person. On the centenary of his birth in 1969, Canada Post issued a six cent stamp to commemorate his life and career.

Awards

- Fellow, Royal Society of Canada (1919)

- Mark Twain Medal (1935)

- Lorne Pierce Medal, Royal Society of Canada (1937)

- Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-Fiction (My Discovery of the West) (1937)

Selected Writings

- Nonsense Novels (1911)

- Moonbeams from the Larger Lunacy (1915)

- Further Foolishness (1916)

- Essays and Literary Studies (1916)

- Frenzied Fiction (1918)

- The Unsolved Riddle of Social Justice (1920)

- My Discovery of England (1922)

- The Garden of Folly (1924)

- Winnowed Wisdom (1926)

- Short Circuits (1928)

- Lincoln Frees the Slaves (1934)

- Humor: Its Theory and Technique (1935)

- Humour and Humanity (1937)

- My Discovery of the West (1937)

- Too Much College (1939)

- My Remarkable Uncle (1942)

- Our Heritage of Liberty (1942)

- Happy Stories (1943)

- How to Write (1943)

- Last Leaves (1945)

- The Boy I Left Behind Me (1946) (an unfinished autobiography)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom