The prime minister (PM) is the head of the federal government. It is the most powerful position in Canadian politics. Prime ministers are not specifically elected to the position; instead, the PM is typically the leader of the party that has the most seats in the House of Commons. The prime minister controls the governing party and speaks for it; names senators and senior judges for appointment; and appoints and dismisses all members of Cabinet. As chair of Cabinet, the PM controls its agenda and greatly influences the activities and priorities of Parliament. In recent years, a debate has emerged about the growing power of prime ministers, and whether this threatens other democratic institutions.

History

The head of the federal government in Canada is called the prime minister. The heads of provincial governments are called premiers. The two terms mean the same thing — first minister or chief minister. Canada adopted the title prime minister from Britain. That country also provided the model for our Westminster parliamentary system. (See Responsible Government; Representative Government.)

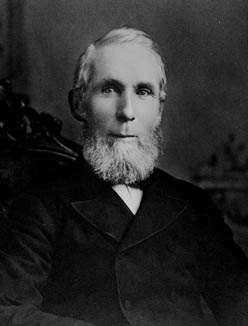

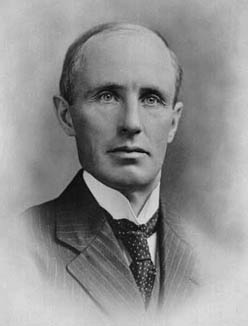

Canada has had 23 different prime ministers since Confederation. Sir John A. Macdonald (who held office from 1867–73 and 1878–91) was the first. Justin Trudeau (2015–) is the most recent. William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 1921–June 1926; September 1926–August 1930; October 1935–November 1948) was prime minister the longest: 21 years, five months. Wilfrid Laurier (1896–1911) was in office for the longest continuous period: 15 years. Sir Charles Tupper (May 1896–July 1896) held office for the shortest period: 68 days. Kim Campbell (June–November 1993) has been the country’s only female prime minister.

Prime ministers have come from across the country, and across the sea. Macdonald and his successor, Alexander Mackenzie, were both born in Scotland. Mackenzie Bowell and John Turner were born in England. Sir John Abbott, from Lower Canada (now Quebec), became the first Canadian-born prime minister in 1891. Quebec and Ontario have provided the most prime ministers — seven and six, respectively. As yet, there have been no prime ministers who were born in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, or any of the territories.

Who Becomes Prime Minister?

Formally, a prime minister is appointed by the governor general. The governor general has little discretion in the matter; except in a crisis, such as the death of an incumbent prime minister.

Prime ministers are not specifically elected to the position. Instead, the PM is the leader of the party that has the right to govern because it enjoys the confidence (or support) of the House of Commons. Usually, the prime minister is elected to a seat in the House as a Member of Parliament (MP). Party leaders can become prime minister even if they are not members of Parliament; however, they would normally seek a seat as soon as possible in a general election or a by-election.

Usually, though not always, the prime minister’s party would have the most seats in the House following a general election. If a prime minister’s party has a majority of seats, his or her government typically holds power for up to four years (or five years, before 2007). A new election must then be called. Prime ministers whose governments last less than four years typically command only a minority of seats in the House. (See Minority Governments in Canada.) The Constitution requires that general elections be held at least every five years. In 2007, Parliament passed a fixed-date election law; it says that a general election will be held on the third Monday in October every four years.

Powers and Responsibilities

The position and responsibilities of a prime minister are not defined in any written law or constitutional document; they instead adhere to constitutional conventions. The prime minister has always been the most powerful position in Canadian politics. The PM controls the governing party and speaks for it. After being appointed to office, they have at their disposal a large number of patronage appointments. They use these to reward the party faithful. The prime minister names senators and senior judges for appointment. They also appoint and dismisses all members of Cabinet — through the governor general — and determine their responsibilities.

As chair of Cabinet, the prime minister controls the agenda and discussions at meetings. They also select the members of Cabinet committees. Because of these factors, and the convention of party solidarity, the PM has great influence over the activities and agenda of Parliament.

The prime minister also enjoys a special relationship with the Crown. The prime minister is the only person who can consult with the governor general, and advise the governor general to dissolve or prorogue Parliament and call an election. Political reality, various conventions, and the Constitution sometimes limit the power of the prime minister. The PM must be wary of offending the various regions of the country. They must also be able to conciliate competing factions within the party and the Cabinet, and throughout Canada.

Neither the prime minister, nor the federal Parliament, have the power to unilaterally amend or defy the rules of the Constitution, the country’s highest law. This can only be done with the consent of the provinces. However, prime ministers can convene meetings with the premiers to discuss and negotiate constitutional change, or any national issue. (See First Ministers Conferences.)

The prime minister has offices in both the Centre Block of Parliament Hill, and in the Prime Minister’s Office and the Privy Council Office (formerly the Langevin Block) on Wellington Street, across from Parliament. The official residence for the prime minister and his or her family is at 24 Sussex Drive, in Ottawa. It is across the road from Rideau Hall, where the governor general lives.

Concentration of Power

As constitutional expert Eugene Forsey writes in How Canadians Govern Themselves (published in 1980): "The Prime Minister used to be described as 'the first among equals' in the Cabinet. [. . .] This is no longer so. He or she is now incomparably more powerful than any colleague. "

The power of prime ministers, even those with large majority governments, was once kept in check by the need to build consensus with other leading members of Cabinet and of the governing party, including those who represented various ideological wings of the party, or different regions of the country. Other institutions, including Parliament itself and the federal bureaucracy, as well as the provincial premiers, also acted as limits on prime ministerial power.

Prime ministers have always enjoyed considerable control over government. Since the 1970s, however, a number of factors have weakened Canada's democratic institutions and expanded the power of prime ministers. The increasing complexity of government has restricted Parliament's power to scrutinize and understand federal taxation and spending and has boosted the size and scope of the Prime Minister's Office (PMO). The 24-hour information age and the pressures of social media have fuelled political partisanship and the desire for increased control over government communications. Where Cabinet ministers once had responsibility for managing policies and programs out of their various departments, today most issues and programs — and almost all communications — are managed and directed by the unelected staff inside the PMO.

At the same time, political parties have become less democratic, less locally-controlled by riding associations, and more centrally controlled by the party leader and his or her advisers, giving the prime minister almost sole control over not just the government, but his or her own party.

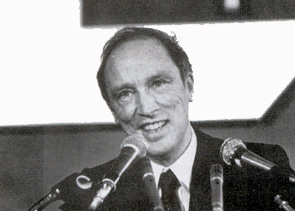

Prime ministers of all political stripes, from Pierre Trudeau to Stephen Harper, have defended the increasing power of their positions and their offices as the necessary requirements of running a modern democratic state. Political scientist and author Donald Savoie, a critic of such concentrated power, argues that Canada's democracy is suffering as a result.

"With Parliament losing relevance, with regional ministers no longer enjoying standing either inside government or in their region, " wrote Savoie in 2015, "we have reached the point where our national political and bureaucratic institutions have lost their way. "

In 2008, political scientist Graham White pointed out that Canadian prime ministers are among the longest-serving leaders among nations with Westminster-style parliaments, thanks in part to the control Canadian prime ministers exercise over their parties and their parliamentary caucuses.

Meanwhile, political scientist Dennis Baker has argued that even today prime ministerial power is not absolute, particularly when members of Parliament combine with public pressure to force governments to change course or amend controversial legislation. Baker has also said that Canada's courts act, not always for the better, as checks on both parliamentary and executive power.

Prime Ministers of Canada

|

Name |

Party |

Term |

|

Conservative |

1867-73 |

|

|

Liberal |

1873-78 |

|

|

Conservative |

1878-91 |

|

|

Conservative |

1891-92 |

|

|

Conservative |

1892-94 |

|

|

Conservative |

1894-96 |

|

|

Conservative |

1896 |

|

|

Liberal |

1896-1911 |

|

|

Conservative |

1911-17 |

|

|

Union Gov |

1917-20 |

|

|

Conservative |

1920-21 |

|

|

Liberal |

1921-26 |

|

|

Conservative |

1926 |

|

|

Liberal |

1926-1930 |

|

|

Conservative |

1930-35 |

|

|

Liberal |

1935-48 |

|

|

Liberal |

1948-57 |

|

|

Conservative |

1957-63 |

|

|

Liberal |

1963-68 |

|

|

Liberal |

1968-79 |

|

|

Conservative |

1979-80 |

|

|

Liberal |

1980-84 |

|

|

Liberal |

1984 |

|

|

Conservative |

1984-93 |

|

|

Conservative |

1993 |

|

|

Liberal |

1993-2003 |

|

|

Liberal |

2003-06 |

|

|

Conservative |

2006-15 |

|

|

Liberal |

2015-Present |

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)