Background

Tentatively titled First Offence, the film was originally conceived within the NFB as a short documentary on parole officers dealing with juvenile delinquents. Owen was given a budget of $35,000 and permission to shoot some re-enactments with actors, but gradually, and somewhat clandestinely, he expanded the project into a narrative feature.

Owen’s shooting script was essentially just a treatment describing the plot; scenes were shot in chronological order and lines were improvised on location. Heavily influenced by the direct cinema documentaries of NFB filmmakers such as Michel Brault and Gilles Groulx, Owen reportedly shot some scenes as many as 20 times in order to achieve a similar tone. Executive producer Tom Daly, the only member of NFB management aware of the film’s shift in size and scope, quietly approved a $75,000 budget to complete it as a feature.

Synopsis

Eighteen-year-old Peter (Peter Kastner) lives with his parents in a middle-class Toronto suburb and rebels constantly against the dead-end materialist values he thinks they represent. While his girlfriend, Julie (Julie Biggs), is also unhappy in suburbia, she has a better relationship with her family than Peter, who is constantly mocking and belittling his parents, his sister and her fiancé.

After yet another argument with his parents, Peter decides to move out on his own. He rents a small apartment and does odd jobs. Julie, meanwhile, also leaves her family. When Peter asks his father (Claude Rae) for a loan so that he and Julie can make a fresh start, he is refused. Angry and embittered, Peter steals money and a car, and resolves to leave Toronto forever.

Analysis

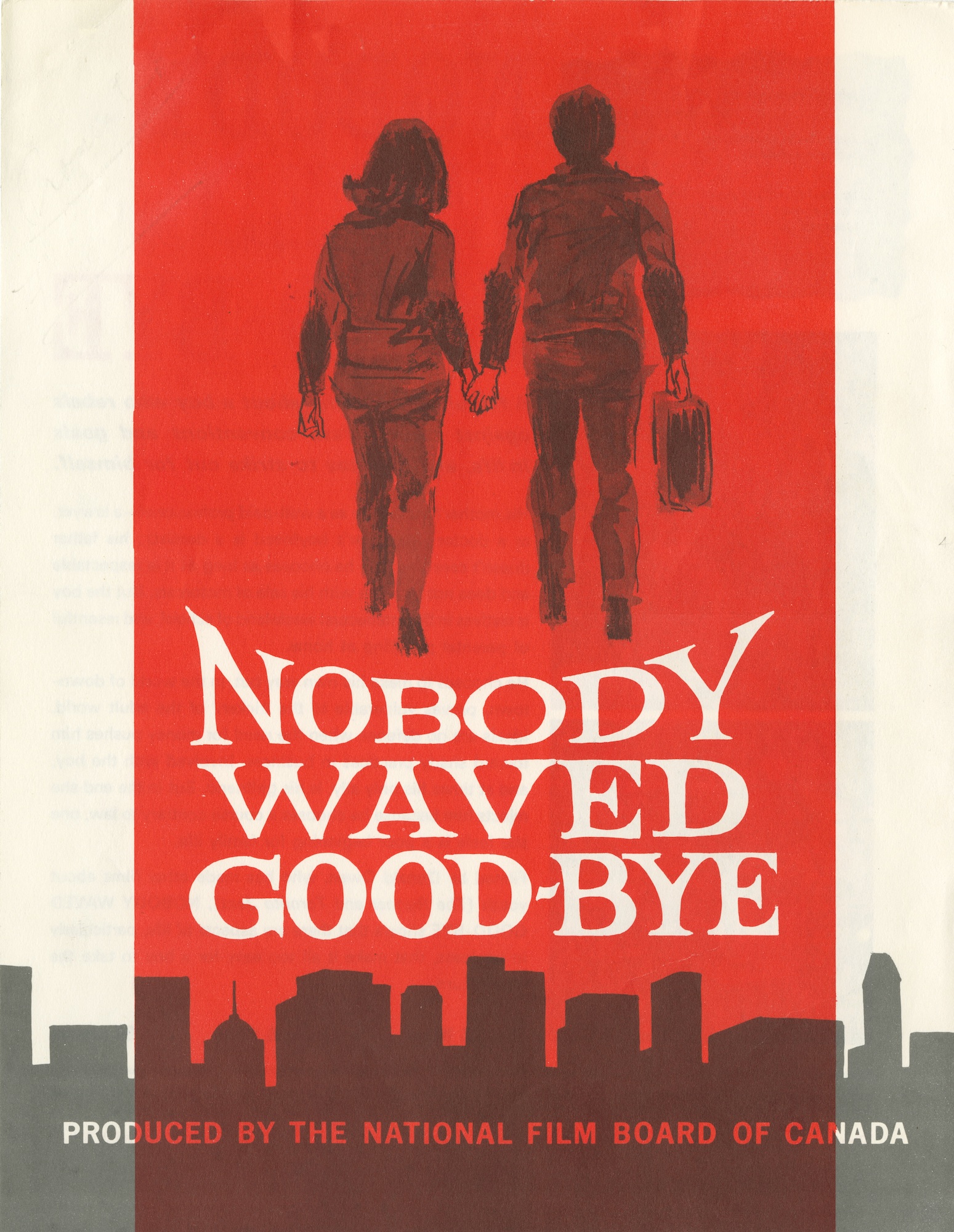

Nobody Waved Good-bye was the first film to examine the serious generational, cultural and economic fissures in postwar Canadian suburbia. It was also an important first step for the still-nascent Canadian feature film industry. One of the first English-language films about the Canadian experience, Nobody Waved Good-bye demonstrated the relevance and dramatic power of our own stories in a medium almost totally dominated by Hollywood.

Critical and Audience Reception

After premiering at the International Festival in Montréal in August 1964, Nobody Waved Good-bye played at a film festival in New York in September, where the Herald Tribune’s Judith Crist gave it a glowing review. Columbia Picture decided to release the film theatrically in Canada, but poor reviews and mediocre box office returns from a limited release in Montréal and Toronto stopped the film in its tracks. However, when independent American distributor Cinema V released the film in cities such as New York, Boston and Los Angeles in the spring of 1965, it received wide acclaim for its raw authenticity. Columbia then released it in Ottawa, Regina, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver, where it was much better received by critics and audiences.

Honours and Legacy

From its low budget, improvisational modes of production to its downbeat narrative of failed rebellion, Nobody Waved Good-bye remains essential viewing for a serious understanding of film culture in Canada. It won a BAFTA Award (for documentary, ironically) in 1965, and was named one of the Top 10 Canadian films of all time in a poll conducted by the Toronto International Film Festival in 1984. That year also saw the release of the somewhat lacklustre sequel, Unfinished Business (1984), which follows Peter and Julie as they cope with their rebellious 17-year-old daughter (Isabelle Marks) while attempting to reconcile their faded ideals with their lives as suburban parents.

In 2016, Nobody Waved Good-bye was named one of 150 essential works in Canadian cinema history by a poll of 200 media professionals conducted by TIFF, Library and Archives Canada, the Cinémathèque québécoise and The Cinematheque in Vancouver in anticipation of the Canada 150 celebrations in 2017.

See also: Canadian Feature Films.

Awards

Flaherty Documentary Award, BAFTA Awards (1965)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom