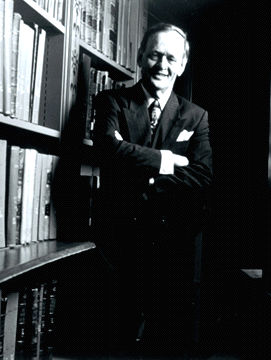

Joseph-Jacques Jean Chrétien, CC, PC, OM, QC, prime minister of Canada 1993–2003, lawyer, author, politician (born 11 January 1934 in Shawinigan, QC). Lawyer and longtime parliamentarian Jean Chrétien was Canada’s 20th prime minister. Early in his political career, Chrétien helped negotiate the patriation of the Canadian constitution as well as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. As Prime Minister, he led the federal government to its first surplus in nearly 30 years. However, his administration also presided over a costly sponsorship program in Quebec that sparked one of the worst political scandals of modern times. His government committed Canadian forces to the Kosovo conflict (1999) and to the war in Afghanistan (beginning in 2002). Chrétien publicly refused to provide direct support for the subsequent American war in Iraq. The recipient of numerous honours and awards, he is involved in several international organizations dedicated to peace, democracy and other global concerns.

Family and Education

Chrétien was the 18th of 19 children, born to a family of modest means. His father, Wellie Chrétien, was a paper mill machinist and Liberal Party organizer. Jean, who would later describe himself as the “little guy from Shawinigan,” was known at school for his temper and for fighting. According to biographer Martin Lawrence’s Chrétien: The Will to Win (1995), one of Chrétien’s classmates wrote in a yearbook that his cauchemar (nightmare) was “[t]o be hit by a punch from Chrétien.” To friend Jean Pelletier, Chrétien was “a fighter. He must win.”

At age 12, Chrétien suffered an attack of Bell’s palsy; it left one side of his face partially paralyzed. He later remarked that he was one politician who did not “speak out of both sides” of his mouth. A member of a staunchly Liberal family, Chrétien became involved in politics at an early age. As a child, he attended rallies and distributed political pamphlets.

In 1957, he married Aline Chaîné. She supported and advised him throughout his political career. The couple would have three children: sons Hubert and Michel and daughter France (she was awarded the Order of Canada in 2011 for voluntary service and philanthropy). In 1959, Chrétien graduated with a law degree from Université Laval and joined a firm in Shawinigan. However, he remained politically active while building his practice.

Early Political Career

In 1963, Chrétien won election to the House of Commons as a Liberal, representing the riding of St-Maurice–Laflèche. He served in Prime Minister Lester Pearson’s Cabinet as minister without portfolio. He then became minister of national revenue. In 1968, he supported Mitchell Sharp for the party leadership.

Under Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Chrétien occupied a number of different portfolios, including treasury board; industry, trade and commerce; finance (the first French Canadian to do so);justice; energy, mines and resources; and Indigenous affairs. When Chrétien was minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, he proposed the 1969 White Paper. It was met with widespread criticism and tremendous backlash and was withdrawn in 1970. Also that year, Chrétien and Aline adopted their son, Michel, from an orphanage in Inuvik.

A strong and emotional speaker, Chrétien enjoyed considerable popularity both inside and outside Quebec. As minister of justice

(1980–82), he directed the federalist forces in the Quebec referendum of May 1980. He then helped devise and implement the federal government’s strategy for the patriation of the Constitution and the enactment of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

(See also Editorial: The Canadian Constitution Comes Home.)

Using a folksy style in English and French, Chrétien created a rapport with his audiences. His forceful and engaging speaking style, strong identification with his audiences, and skills as a political organizer were amply demonstrated in 1984; he ran second to John Turner in the Liberal leadership campaign. Chrétien retained his seat in the subsequent election, which saw the Liberals lose power. However, he grew restive in opposition. With Turner’s leadership renewed at a party convention in 1986, Chrétien resigned his seat in the House of Commons. He returned to a private law practice. Around this time, he also published the autobiographical Straight from the Heart (1985), which quickly became a bestseller.

Liberal Leader

John Turner resigned the leadership in 1990 after a second defeat by the Conservatives. This time, Chrétien succeeded in winning the Liberal leadership, defeating Paul Martin. Chrétien returned to the House of Commons in 1990, representing the New Brunswick riding of Beauséjour.

Chrétien inherited a party that was disorganized and almost bankrupt. Moreover, his opposition to the Meech Lake Accord in 1990 cost him support among Quebec nationalists. The failure of the Charlottetown Accord in 1992 also contributed to calls for sovereignty in the province. (See also Charlottetown Accord: Document.)

However, Chrétien’s Liberals were well prepared for the election of October 1993. Chrétien ran an almost flawless campaign; he targeted the issue of job creation and released a detailed platform (the “Red Book”) that effectively answered criticisms that he would return to the high spending levels of previous Liberal governments. Chrétien recaptured his old riding of St-Maurice and managed to win 19 seats in Quebec, despite the rise of the Bloc Québécois.

Elsewhere in Canada, the campaign was a triumph. The Liberals won a clear majority, with 177 seats overall. Chrétien was sworn in as Canada’s 20th prime minister.

First Term as Prime Minister (1993–97)

The Chrétien government inherited a difficult legacy; but it was also fortunate in the period in which it governed. Under Kim Campbell, the Conservative Party had disintegrated, falling from 151 seats to 2. Support for the NDP had also collapsed. This left Chrétien’s Liberal Party as the only national party in the House of Commons to face the regional blocks represented by the Reform Party and the Bloc Québécois.

Canada in 1993 had high taxes, a high national debt and an alarming annual deficit. Chrétien made it a priority to cut or limit federal programs, including subsidies to the provinces, and to eliminate the deficit. The Liberals also kept the unpopular Goods and Services Tax (GST), even though Chrétien had once promised to abolish it. Fortunately for Chrétien, economic conditions were good, and revenues rose. In 1998, Canada registered its first surplus in nearly 30 years. In spite of the Liberal budget cuts, Chrétien and his finance minister, Paul Martin, enjoyed high public approval in comparison to the political opposition, which remained in disarray.

Chrétien was somewhat less fortunate when it came to the perennial issue of Quebec separatism. In the Quebec referendum of October 1995, the federalist forces scraped by with the barest victory. Chrétien’s role in the campaign was severely criticized.

Break-In at 24 Sussex Drive

Not long after the Quebec referendum, an armed intruder broke into the prime minister’s residence. As recounted in his later trial, André Dallaire heard voices instructing him to kill the prime minister and avenge the results of the vote. After scaling the fence, he smashed a window and entered the house. Woken by the noise, Aline went to investigate and was confronted by Dallaire just outside the bedroom door. After retreating to the bedroom and locking the door, she woke her husband and then called the RCMP security team. Chrétien grabbed an Inuit carving of a loon from a bedside table to defend himself. However, Dallaire never attempted to enter the bedroom; he was eventually apprehended by the RCMP. He was later convicted of attempted murder but was not held to be criminally responsible, on the grounds that he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

Sponsorship Scandal

The results of the Quebec referendum made it clear that Chrétien’s popularity in his home province was limited. Chrétien tried to remedy the situation through an ill-conceived and largely secret “sponsorship” program; it was designed to raise the profile of both Canada and the federal government in Quebec through a targeted advertising program. However, the program instead turned into a multi-million-dollar scandal that did little to create support for federalism.

Revelations in the Globe and Mail prompted a series of investigations, including an RCMP investigation and the high-profile Gomery Inquiry; it found that public money had been used to enrich Liberal-friendly advertising firms and to provide kickbacks and campaign funds to the Quebec wing of the federal Liberal Party. Chrétien testified at the Gomery Inquiry in 2005. Although he was not personally implicated in the scandal, the affair politically hobbled his successor, Paul Martin. It also tainted the Liberal brand in Quebec for years to come.

Foreign Policy

In foreign policy, the Liberals stressed economic diplomacy above all during Chrétien’s first term. Chrétien himself led a series of highly publicized “Team Canada” missions to various countries and regions. In terms of photo opportunities and favourable media, these may have been triumphs; but critics charged the government with overlooking human rights abuses in countries such as China and Indonesia for the sake of trade. The longer-term economic benefits of these trade missions have also been debated. In Canada-US relations, Chrétien established a low-profile but evidently cordial relationship with US president Bill Clinton.

Second Term as Prime Minister (1997–2000)

In 1997, Chrétien called a federal election for 2 June. The opposition parties were fragmented and unimpressive, and regional rather than national in their appeal. As a result, Chrétien won the election with a small but serviceable majority of 155 seats out of 301. In its second term, the Chrétien government continued to benefit from prosperity; despite economic troubles in Asia and a sluggish economy in Europe. Its foreign policy, under new minister Lloyd Axworthy, appeared to switch emphasis toward human rights issues. As a result, Canada was a participant in NATO’s Kosovo War in 1999.

With the economy ticking along and Chrétien’s finance minister, Paul Martin, widely admired, there appeared to be no major administrative or policy problems by the end of 1999. Chrétien turned his attention to domestic politics. The most obvious threat to the Liberals came from the right. The Reform Party was attempting to recast itself so as to absorb the remnants of the Conservatives. A “unite-the-right” movement took shape in the form of the Canadian Alliance Party in early 2000. The Alliance promptly elected a new and untried leader (at least at the federal level), Stockwell Day. Chrétien saw a political opportunity and seized it, forcing an election on an unenthusiastic Liberal Party.

But if rank-and-file Liberals were hesitant, the Alliance Party and its leader were dismally unprepared. On 27 November, Chrétien secured a third straight majority with 172 seats and nearly 41 per cent of the vote. Best of all, from Chrétien’s point of view, the Liberals outpaced the Bloc Québécois in the popular vote in Quebec.

Third Term as Prime Minister (2000–03)

The main problem during Chrétien's third term was relations with the United States. Canada, as always, was overwhelmingly dependent on the American market for its exports. This posed no great problem during the peaceful 1990s. However, when the US came under attack from Islamic terrorists on 11 September 2001, the security of US borders became a serious issue for the first time since the Second World War. Canadians generally, and Chrétien in particular, supported the Americans; but decades of neglect and underfunding had left Canada with a weak armed forces and limited resources with which to respond to the crisis. Canada sent what troops it could to the war in Afghanistan beginning in early 2002; but Chrétien refused to participate directly in the Iraq war. He declared that Canada would not do so without authorization by the UN Security Council.

Chrétien’s stand on Iraq proved immensely popular in Canada, especially in Quebec. But it could not save him from rising discontent in his own party. Supporters of the finance minister, Paul Martin, had succeeded in undercutting Chrétien’s followers. Chrétien finally announced that he would step down as Liberal leader. His last official act was to give a bravura speech at the Liberal convention in Toronto in November 2003; he resigned as prime minister the following month. Martin, the Liberal Party’s new leader, replaced Chrétien as prime minister on 12 December 2003.

Retirement

After retiring from political life, Chrétien became counsel for the law firm Heenan Blaikie LLP. In February 2014, after the collapse of Heenan Blaikie, he joined law firm Dentons Canada as counsel.

Chrétien has also remained involved in politics, if not on an official basis. In 2008, he and former NDP leader Ed Broadbent worked to form a coalition agreement between the Liberals and the NDP to oust the Conservative government led by Stephen Harper. Harper managed to prorogue parliament and halt the coalition’s efforts to put forth a motion of non-confidence. In 2013, Chrétien publicly criticized Harper’s foreign policy; this sparked a public debate about the international stature of the country under different governments.

Since retiring, Chrétien has been involved in various international organizations. He is a member of the World Leadership Alliance–Club de Madrid, a group of former world leaders that consults on challenges facing democratic governments. He is also on the Honour Committee of the Fondation Chirac, an organization dedicated to world peace. In 2008, Chrétien became co-chair of the InterAction Council; it develops and recommends practical solutions to problems facing the global community.

See also Timeline: Elections and Prime Ministers.

Honours and Awards

- Queen’s Privy Council for Canada (1967)

- Companion, Order of Canada (2007)

- Order of Merit (2009)

- Queen’s Counsel

Honorary Degrees (Canadian Universities)

- Wilfrid Laurier University (1981)

- Laurentian University (1982)

- University of Western Ontario (1982)

- York University (1986)

- University of Alberta (1987)

- Lakehead University (1988)

- University of Ottawa (1994)

- Memorial University of Newfoundland (2000)

- Queen’s University (2004)

- McMaster University (2005)

- Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (2008)

- Concordia University (2010)

- Université de Montréal (2011)

- University of Winnipeg (2014)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom