Early Life and Education

John McCrae was a descendant of Scottish immigrants. Like his older brother Thomas and younger sister Geills, McCrae was educated in Guelph, Ontario. He was a member of the Guelph Highland Cadet Corps and in 1887 he earned a gold medal as the best-drilled cadet in Ontario. A gifted student, he received his bachelor’s degree (1894) and medical degree (1898) from the University of Toronto. While a student, McCrae published poetry in a number of Canadian and British publications.

During the summer of 1899, McCrae worked at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, with Sir William Osler, who was already a world-renowned physician. Later that year, McCrae was granted a fellowship at McGill University in Montréal. But he postponed the work for a year and travelled back to Guelph, where he enlisted in a local battery.

For a year, McCrae and D Battery of the Royal Canadian Field Artillery took part in battles in the South African War (1899–1902). He was quickly promoted to captain, then to major. In one incident, McCrae nearly drowned while crossing a stream on horseback. He returned to Canada in January 1901, where he gave a public lecture about the employment of artillery during the war.

Medical Career

John McCrae returned to McGill University and continued the advanced studies he had put aside during his war service. He was appointed as an associate of medicine at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montréal and was a lecturer at the university. McCrae also worked as a pathologist at Montreal General Hospital, as a doctor for the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Infectious Diseases, and in his own private practice. Until 1911, McCrae took the train once a week to the University of Vermont in Burlington, where he worked as a visiting professor of pathology.

Before the First World War, McCrae co-wrote an 878-page volume entitled A Text-book of Pathology for Students of Medicine with J. George Adami. McCrae was also a member of various Montréal social groups, such as the Pen and Pencil Club, where he shared his poetry. Canadian writer and humourist Stephen Leacock was a close friend of McCrae’s during his Montréal years, and the two men were founding members of the University Club of Montreal. They chose Canadian architect Percy Erskine Nobbs, one of Canada’s foremost architects, to design their clubhouse.

In 1910, Governor General Earl Grey invited McCrae to be the on-duty physician for a canoe expedition to Hudson Bay and beyond. The government wanted to establish a new rail link to a northern port to more easily transport wheat from the prairies. Grey’s group of 38 men, including 23 Cree guides, travelled for two weeks from, Norway House on Lake Winnipeg to York Factory on Hudson Bay, where the guides were left. The remaining 15 men made the last four weeks of the trip aboard the icebreaking freight and passenger steamer The Earl Grey, aboard which they travelled south to Prince Edward Island, then to Québec City. While making the rail line did not prove to be feasible, the trip provided McCrae with ample opportunity to observe the lives of Canada’s Indigenous peoples and record the information in written word and notebook sketches. During the trip, McCrae entertained the group with his story-telling. He met another writer, Lucy Maud Montgomery, when Earl Grey’s steamship anchored off Prince Edward Island; the Governor General was a fan of the Anne of Green Gables author.

First World War

When Britain declared war against Germany on 4 August 1914, John McCrae was on a ship bound for England on a rare holiday from his heavy work schedule. Instead, upon his arrival he rushed to offer his services to the army. He was 41 years old and had resigned from the army 10 years before, and though he was not wanted as an artillery officer, he was offered a position as a doctor.

McCrae was appointed Medical Officer in the 1st Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery and returned to Canada to prepare at Valcartier, Québec, for duty at the front. Before he left Montréal for what would be the last time, McCrae took his personal belongings to a storage facility, wrote to his family in Guelph, and visited the William Notman & Son photographic studio ( see William Notman), where he sat for the portrait that has become his best-known image.

“In Flanders Fields”

Newly-promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, John McCrae treated soldiers’ wounds at the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium (22 April to 25 May 1915). The battle was the first in which poison gas was used as a weapon, resulting in lung damage and death. McCrae’s lungs were damaged by the gas, making his asthma much worse; nevertheless, he tended soldiers at Essex Farm dressing station near Ypres — a bunker with a dirt floor and with light provided only by lanterns and the doorway.

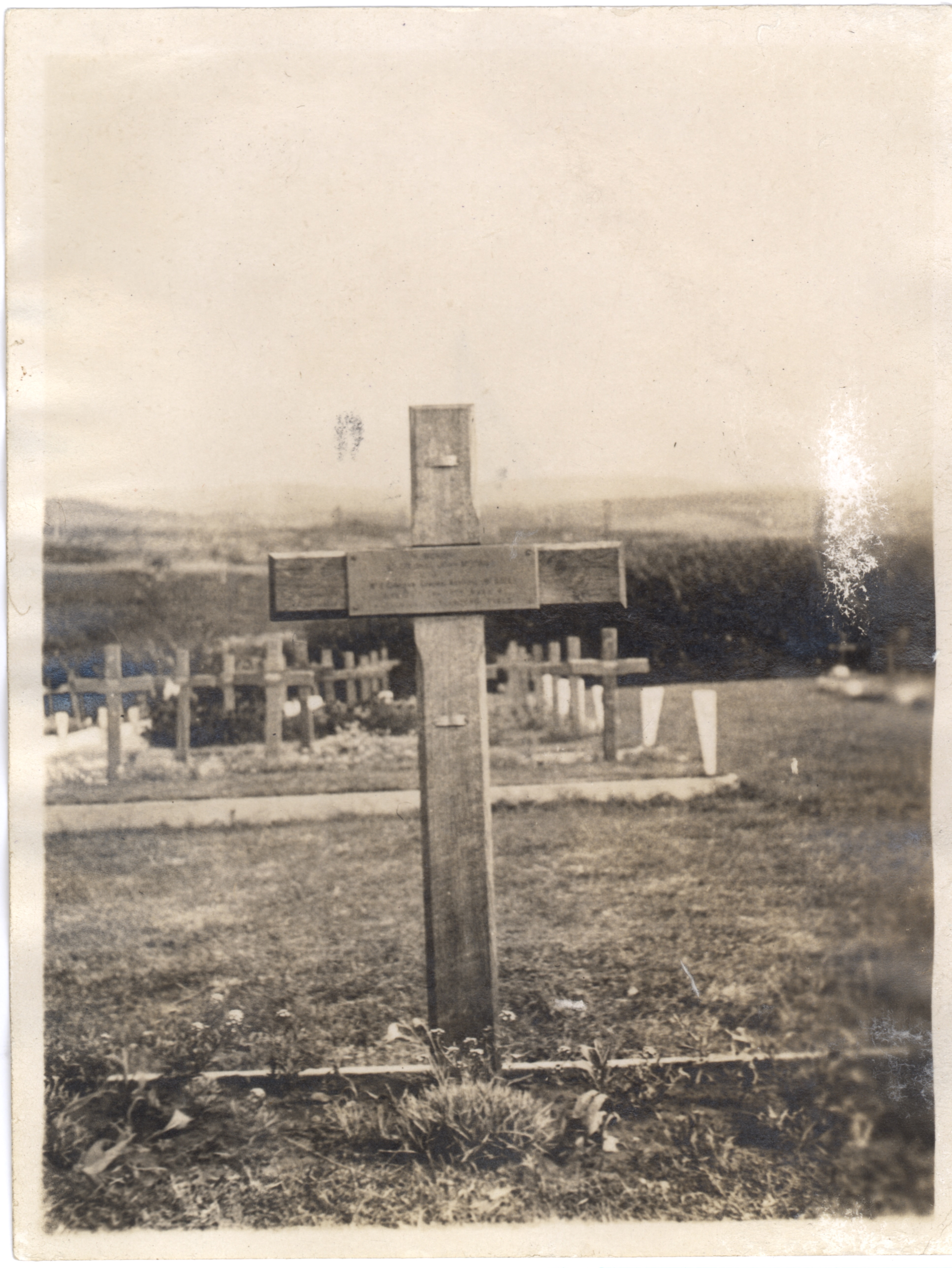

One particular soldier’s death during the battle profoundly moved McCrae. Lt. Alexis Hannum Helmer was a 22-year-old civil engineer and a graduate of McGill University. McCrae had not known Helmer in Montréal, but the two men had become good friends during the war. On the morning of 2 May 1915, Helmer was killed when a German shell exploded at his feet. His remains were gathered into an army blanket and buried in nearby Essex Farm Cemetery. As the officer present, McCrae officiated at Helmer’s graveside service. A wooden cross marked the burial place.

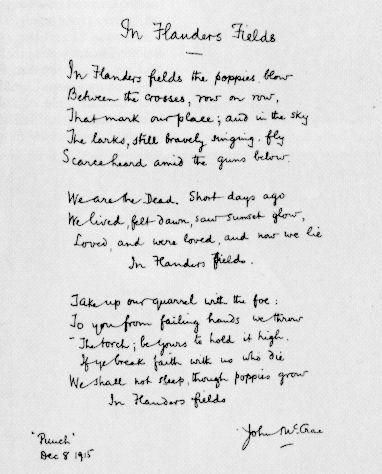

The next morning, McCrae wrote the poem “In Flanders Fields.” While there are different accounts of exactly how and where McCrae wrote those 15 lines — on an ambulance step, inside the dressing station — they are not as important as the poem’s content and enduring potency.

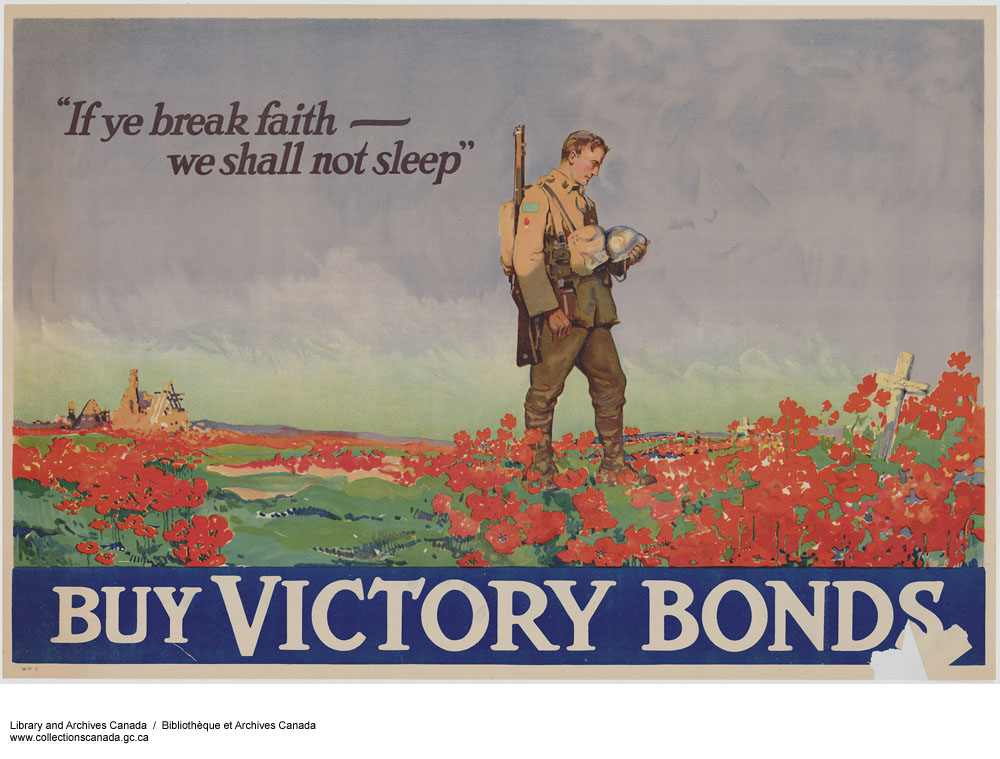

In the horrific setting of hastily-built cemeteries alongside active battlefields, red poppies sprang from the bombarded soil. Birds sang despite the deafening sounds of war. In just a few lines, McCrae called upon the living to join the war effort so that Helmer and millions of other soldiers in the First World War would not have died in vain.

After being rejected by The Spectator (a popular magazine from London), “In Flanders Fields” first appeared in the 8 December 1915 edition of the British magazine Punch. However, McCrae’s name did not appear with the poem, and the poem’s placement was unfortunate — tucked into the bottom corner of the left-hand page. However, the public noticed the poem and it was soon being memorized, copied into letters, set to music and translated into multiple languages. The poem was also used to raise $400 million for the war effort.

By the time “In Flanders Fields” was published, McCrae had moved to the No. 3 Canadian General Hospital near Boulogne-sur-Mer, France, near the English Channel. There were more than 1,000 wounded and dying soldiers at the hospital. Contrary to popular belief, McCrae knew that his poem had become popular all over the world and he was pleased at the acclaim it received. However, little attention was paid to other poetry he wrote, such as “The Anxious Dead” in 1917. But in 1919 — the year after his death — the public’s interest in all things related to McCrae was reflected in the brisk sales of Sir Andrew Macphail’s collection of McCrae’s poetry, which was published with a short biography.

By January 1918, McCrae had provided medical care for troops in the British Expeditionary Force for more than three long years. This dedicated service was noticed, and McCrae was appointed as the consultant physician to the First British Army — the first Canadian to be named to the position. McCrae, however, would never take on his new tasks. Weary and weakened, he was susceptible to pneumonia — a condition that killed many troops during the First World War. On 23 January 1918, he became ill. On 28 January, McCrae died of pneumonia and meningitis at the No. 14 British General Hospital in Wimereux, France. He was 45 years old.

McCrae was buried the next day in the Wimereux Communal Cemetery with full military honours. Bonfire, his beloved horse, was part of the funeral procession and General Arthur Currie was in attendance. Nursing sisters found a few poppies to put on McCrae’s grave on that unseasonably warm and sunny winter day.

Legacy

John McCrae’s birthplace is now a museum and a National Historic Site of Canada.

In 2015, McCrae was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame for his valuable contributions to the field of pathology.

Also in 2015, in honour of the 100th anniversary of the writing of “In Flanders Fields,” a statue of McCrae created by sculptor Ruth Abernethy was unveiled in Ottawa. A duplicate statue is within sight of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, his family’s place of worship, and looks out over his hometown of Guelph, Ontario.

Between 2001 and 2013, an excerpt of “In Flanders Fields” appeared on the back of the Canadian $10 bill.

The red poppy remains a symbol of sacrifice and remembrance in many parts of the world (see Remembrance Day).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom