Ontario has not granted its French-speaking citizens political autonomy or recognized the equality of its French-speaking and English-speaking language communities (as New Brunswick has). But the government of Ontario did grant French equal status in the province’s courts in 1984 and pass the French Language Services Act in 1986. As a result, in Ontario, provincial government services are now delivered in French as well as English in 26 designated regions, and French-language institutions, in particular community colleges and health centres, have acquired a degree of autonomy.

French in Ontario (1867–1960)

In the negotiations leading to Canadian Confederation, the constitutional rights of the Protestant minority in Quebec and the Catholic minorities in the other provinces were a contentious issue. Section 93 of the British North America Act (BNA Act) of 1867 recognized public funding of separate schools for the religious minority. The BNA Act also allowed the use of either language in the courts of Canada and Quebec, the Canadian Parliament and the Quebec legislature, but section 133 required the use of both languages in the records and journals of these legislative bodies and in the laws that they pass. The BNA Act did not, however, expressly recognize the right to education in French outside of Quebec. As a result, education in French was suspended in all of Canada’s majority English-speaking provinces for various lengths of time and to varying extents between 1871 and 1931, leading to crises about these provinces’ responsibilities for the education of their French-speaking minorities (see New Brunswick Schools Question; Ontario Schools Question; Manitoba Schools Question; North-West Schools Question).

In 1927, the government of Ontario suspended the enforcement of Regulation 17, thus allowing Franco-Ontarian schools to resume teaching in French. The province established an office for French education and developed a “Special French” course for French Canadians attending public high schools in the province. In 1942, Ontario recognized the Association canadienne-française d’éducation d’Ontario (ACFÉO, founded in 1910) as the body representing Franco-Ontarians and granted it annual funding for education services.

Constitutional Renewal (1960–82)

After the Second World War, the growth of the welfare state led the ACFÉO to demand that the provincial government provide more services to meet the needs of Franco-Ontarians. In 1961, the ACFÉO suggested that the government make Ontario road signs bilingual. At its 1962 congress, the ACFÉO asked that all provincial government services be offered in French as well as in English. The central goal of this new quest for social justice was to secure not only equality for all Ontarians, but also, for French-speaking Ontarians, special rights equivalent to those afforded to English-speaking Quebecers. But the province confined improvements to the fields of education and culture. In 1963, it granted primary-school teachers the right to teach in French. In 1968, it extended this right to teachers in secondary schools as well. In 1969, the Ontario government established French-language organizations within TVOntario and the Ontario Arts Council.

At a federal-provincial conference in February 1968, as the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963–70) and the Ontario Advisory Committee on Confederation (1967–70) carried on with their work, Ontario premier John Robarts considered making French an official language of the province’s legislature. Then, during the discussions preceding the drafting of the Victoria Charter (1971) — a set of proposals presented by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau to repatriate and amend the Canadian Constitution — Robarts agreed that Ontario would recognize the right for members of its legislature and public service to express themselves in French, and for French-speakers to receive the services of an interpreter, if needed, in Ontario’s courts. But the Victoria meeting ended in failure, and in 1972, Robarts’s successor as premier, William (Bill) Davis, adopted a policy of simply providing services in French. This policy made it possible, for example, to issue bilingual driver’s licences and to have public documents translated.

The Association canadienne-française de l’Ontario (ACFO) seized on the new policy as an opportunity to meet with Ontario health minister Frank Miller. In 1974, he agreed to have Dr. Jacques Dubois conduct a study on the delivery of health services in French. This study revealed the insufficient bilingualism of medical staff in many regions of the province. In the legal sphere, activists in a movement called C’est l’temps (1975) demanded the right to services in French; for example, they refused to pay unilingual English tickets, even if that meant spending a few nights in jail. These pressure tactics gained the attention of Attorney General Roy McMurtry, who authorized the first Ontario trial ever to be held in French, in Sudbury in 1976.

At its 1977 conference, the ACFO demanded passage of a law that would set out a comprehensive framework for providing all provincial services in French and would officially recognize the Franco-Ontarian population. In 1978, the ACFO submitted a brief, inspired by 120,000 telegrams, letters and petition signatures, with the goal of securing recognition of Franco-Ontarians’ fundamental right to receive services in French. In spring 1978, the ACFO’s efforts to raise awareness among the official opposition led Albert Roy, Liberal member of the Legislative Assembly for the riding of Ottawa East, to table a private member’s bill ensuring services in French in the various areas of activity falling under provincial jurisdiction.

This bill made it through Second Reading but was then vetoed by Premier Davis. He believed that his government had already adopted a number of similar policies supporting services in French. He defended his use of “baby steps” to bring anglophone public opinion along gradually, and tried instead to gain political advantage in negotiations with school boards that refused to open French-language secondary schools. Even though French did not have the status of an official language in Ontario, its ministries of Health and of Community and Social Services, in 1979 and 1980, respectively, adopted policies on services in French and bilingualism in signage and documentation in certain regions where demand warranted. Starting in 1981, municipal councils were allowed to hold meetings in French. Then, in 1984, Attorney General McMurtry granted French equal status before the courts.

Adopting a Comprehensive Statute on Services in French (1985–89)

In September 1985, a Liberal minority government led by David Peterson took power, with the support of the New Democratic Party. In May 1986, Liberal member of the Legislative Assembly Bernard Grandmaître tabled Bill 8, which was to become the French Language Services Act. Its preamble stated that French was an historic language in Ontario, was recognized by the Constitution as an official language in Canada and was recognized in Ontario as an official language in the courts and in education, and that it was desirable to guarantee the use of French in institutions of the Legislature and the Government of Ontario.

But Grandmaître hastened to emphasize that this bill would not introduce official bilingualism, a step to which three-quarters of Ontario voters would have been opposed. As another member of the Legislature, Jean Poirier, remembered years later, this compromise represented the most that a majority was willing to accept. “It was that or nothing,” he recalled, adding that Bill 8 will probably not lead to official bilingualism. For Premier Peterson, Bill 8 also represented a gesture of good faith toward Quebec, which was then looking for an honourable way to accept the constitutional agreement of 1982 (see Constitution Act, 1982). Peterson felt that Bill 8 could serve as an example of how federalism could show flexibility toward and respect for francophone minorities. Bill 8 achieved such a consensus in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario that it was passed unanimously on Third Reading.

The French Language Services Act received Royal Assent on 18 November 1986, but did not come into force until three years from that date, so that the provincial government would have time to meet the new obligations that it imposed. This Act designated 23 areas (cities, municipalities, counties and districts) where there were at least 5,000 francophones or where francophones represented at least 10 per cent of the population. For citizens in these areas, the Act conferred the right to communicate in French with any head or central office of a government agency or institution of the Legislature. (As of 2018, there were 26 designated areas.)

From 1986 to 1989, the province began increasing funding for bilingual universities so that they could establish and enhance French-language programs in health-related fields, while the new Office of Francophone Affairs began recruiting the francophone professionals that it needed for its staff. The ACFO held consultation forums in Ottawa and Sudbury to identify steps to correct the shortcomings in the specialized health services available in French in the province. One necessary step thus identified was the creation of francophone community health centres where Franco-Ontarians would have the autonomy needed to design, deliver and manage their own health services, in accordance with their own particular needs and collective aspirations.

The Act Comes into Force and Meets Resistance (1989–90)

When the French Language Services Act came into force on 9 November 1989, Franco-Ontarians celebrated to the tune of “Notre place” (Our Place), written and sung by Paul Demers to mark the occasion. But they met with resistance from many quarters. The Alliance for the Preservation of English in Canada (APEC), which had opposed the Act ever since its passage in 1986, ran a disinformation campaign, sowing fears that this law threatened anglophone public servants’ jobs and would impose French on unilingual anglophone Ontarians. Municipalities and universities, even though they received most of their funding from the province, protested and succeeded in exempting themselves from the obligations that the Act imposed. There were even dark murmurs about a plot to make French an official language with primacy over English in Ontario. During the 1987 provincial election campaign, the Progressive Conservative party attempted to use such fears to its advantage, while the ACFO joined forces with pro-French organizations such as Canadian Parents for French to defend their limited but hard-won gains.

Meanwhile, the negative reactions continued. Some 10 municipalities, from Niagara Falls to Brockville, considered resolutions declaring them to be unilingual English entities. In response to public petitions, the cities of Thunder Bay and Sault Ste Marie passed such resolutions a few weeks after the adoption of the Act, even though it in fact imposed no requirements on municipalities. (The Court of Appeal for Ontario invalidated these resolutions in 1994.) The ACFO acknowledged that it had underestimated the APEC’s impact not only on public opinion but also on Canadian unity, thus re-emphasizing the precariousness of Franco-Ontarians’ language rights. In 1990, in response to this situation, francophone members of 45 municipal councils in Ontario formed the Association française des municipalités de l’Ontario. Franco-Ontarians also launched a campaign to make the City of Ottawa officially bilingual; as of 2018, this campaign had not yet achieved its goal.

Institutional Autonomy for One Francophone Hospital and Several Francophone Colleges (1990–2002)

The French Language Services Act provided increased autonomy for francophone institutions in the health and education sectors. In addition to allowing francophone community health centres to be established, the Act provided support for the Franco-Ontarian campaign to create a 23rd community college in Ontario. Since the 1970s, Franco-Ontarian students and administrators had been lobbying for the development and consolidation of college-level courses and programs offered in French in Ottawa, Sudbury, Timmins and Cornwall. The ACFO demanded that the programs be consolidated into at least one French-language college, rather than scattered across the province’s 26 designated areas. Although the government of Ontario had not planned such a move, in January 1989 it agreed to provide equal funding with the federal government to found the province’s first French-language community college, La Cité collégiale, in Ottawa, in 1990. But in the north and the south of the province, the NDP government of Bob Rae, elected in September 1990, dragged its feet. It was not until 1993 that it announced the planned opening of Collège Boréal in Sudbury and Collège des Grands-Lacs in Toronto in 1995 (the latter eventually closed, in 2002). But then the plan to combine French-language university programs into an autonomous Franco-Ontarian university failed, and no Ontario city became officially bilingual, because the French Language Services Act had exempted them from these obligations.

Originally regarded by some as a start toward official bilingualism, the French Language Services Act gradually appeared to be as far as Ontario was prepared to go. In February 1997, the Progressive Conservative government of Mike Harris announced its intention to close Hôpital Montfort (Montfort Hospital) in Ottawa — Ontario’s largest French-language hospital and only French-language teaching hospital. An activist organization called SOS Montfort was immediately formed to fight this move, and in response, in August 1997, the province revised its plan: the hospital would not close, but its budget and services would be reduced substantially. In 1998, SOS Montfort and Hôpital Montfort applied to the Divisional Court of Ontario to have this new plan struck down (Lalonde v. Ontario (Commission de restructuration des services de santé)). Attorney Paul Rouleau argued that the government’s plans violated the French Language Services Act, and that the spirit of this Act and of the Constitution of Canada provided mechanisms for consulting and empowering the Franco-Ontarian community. In November 1999, the Divisional Court found in favour of the applicants, but in December 1999, the government appealed this ruling. Two years later, on 7 December 2001, the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled in favour of SOS Montfort and the hospital.

Some Progress under the Liberals (2003–18)

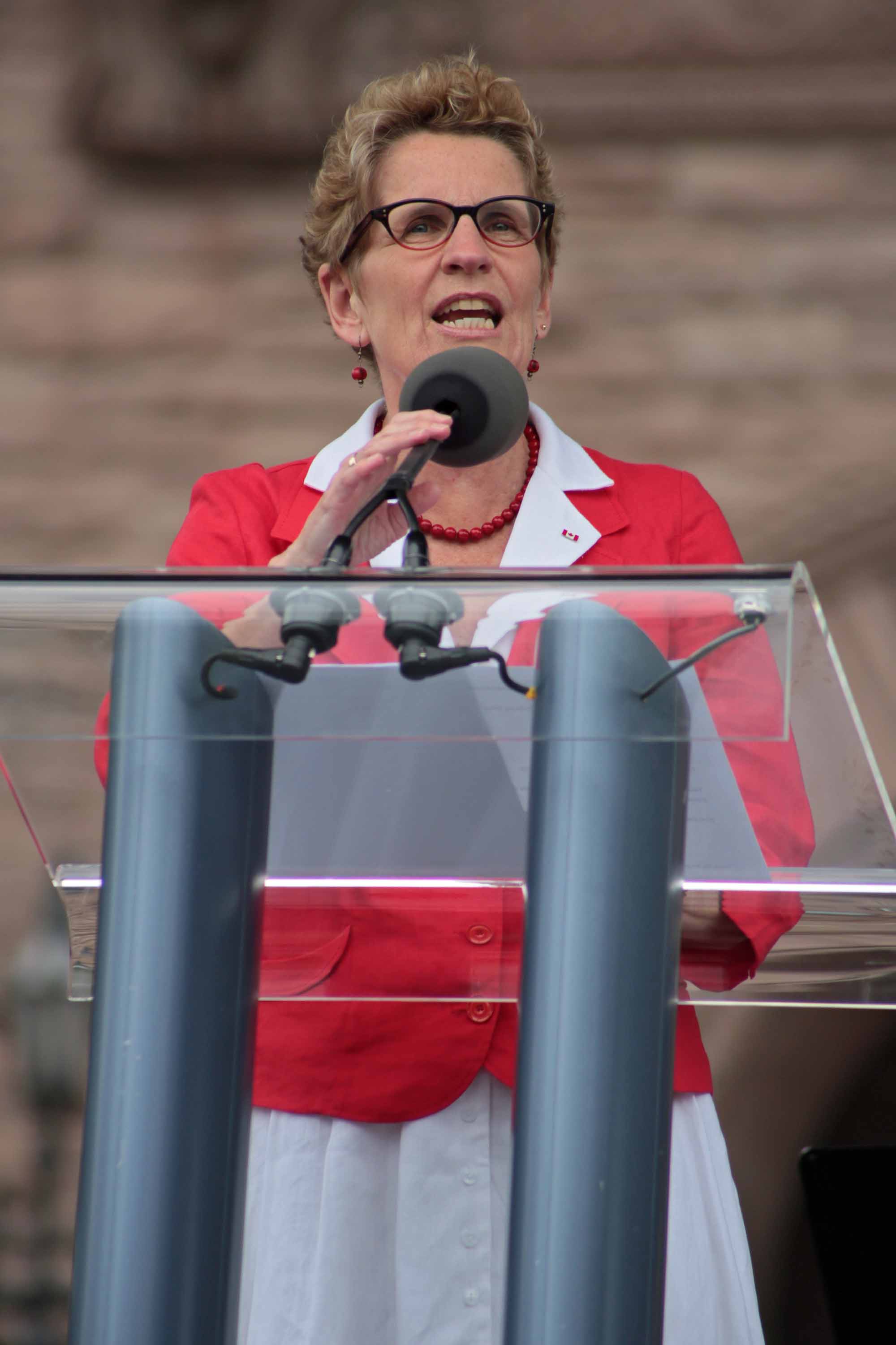

Under the Liberal governments of Dalton McGuinty and Kathleen Wynne, the Act was strengthened in certain respects. In 2007, the Office of the French Language Services Commissioner was established to ensure compliance with the Act. Reporting directly to the Ontario legislature, its role was to ensure respect for the province’s French Language Services Act. Mr. François Boileau was appointed to the position in August 2007. When the cities of Kingston and Markham reached the francophone-population thresholds specified in the Act, they became designated areas, in 2009 and 2018, respectively. Then the bilingual universities were designated (partially), between 2011 and 2013.

In 2013, the Liberal government made the French Language Services Commissioner accountable to the Legislative Assembly, rather than to the Minister Responsible for Francophone Affairs. As a result, the Commissioner became an independent Officer of the Legislative Assembly, and the office itself became independent of the government. But the Liberals also rejected some requests. They refused to make the cities of Oshawa and Vaughan designated areas, even though they had met the eligibility criteria specified in the Act and had taken steps to secure this status. The Liberal governments also declined to combine French-language university programs into a provincial Franco-Ontarian university and to overhaul and constitutionalize the Act. According to legal experts Mark Power, François Laroque and Albert Nolette, constitutionalizing the Act would have made it possible to increase the powers of the Commissioner’s office, expand the obligations of the professional colleges and begin the process leading to official bilingualism.

In 2016, Mr. Boileau’s term as Ontario’s French Language Services Commissioner was renewed by the Legislature for another five years.

In July 2017, Kathleen Wynne’s Liberal government replaced the Office of Francophone Affairs with the new Ministry of Francophone Affairs. Bill 177, passed the same year, acknowledged the bilingual character of the City of Ottawa and established plans for a French-language university, l’Université de l’Ontario français, in the greater Toronto area.

Challenges under Progressive Conservative Government (2018 - present)

Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government was elected in June of 2018 and soon returned the Ministry of Francophone Affairs to its former status as the Office of Francophone Affairs. In November 2018, the new government announced it would abolish the Office of the French Language Services Commissioner, get rid of the responsibility to initiate inquiries and formulate recommendations, merging only the complaints service into the office of the Ontario Ombudsman. The government also announced it would suspend plans and funding for the French-language university.

See also Primary Source Document: Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom