Why Do Floods Occur?

The main cause of river flooding is excessive runoff following heavy rains. The rate of runoff can be increased by urbanization (i.e., the conversion of open land to water-resistant surfaces such as roads and buildings), and by removal or change of vegetative cover (water runs off cropland faster than forested land). Runoff is also augmented by snowmelt in early spring. For much of Canada, spring is the peak flood season.

Floods can also be caused by ice jams, when upstream water is blocked by accumulations of ice. This often occurs at a constriction point in a river such as a bridge or a narrow channel. Heavy storms can cause floods in the summer months, especially in small watersheds.

In snowmelt and spring runoff floods, a river generally rises slowly, allowing time for the construction of temporary defenses or evacuation. By comparison, in storm floods water can rise quite quickly. Similarly, when an ice jam breaks up, the resulting rush of water can be very rapid.

High-water problems also occur on lakes, but usually the rate of rise and fall of the lake’s water level is much slower than on rivers. Damage to shoreline installations and cottages is not uncommon on the Great Lakes as well as others.

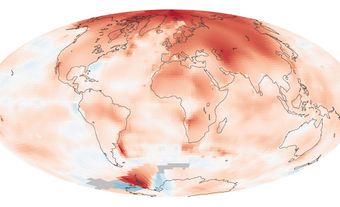

Coastal flooding may be caused when storm activity augments seasonally high tides, or when a tsunami, generated by an earthquake, is driven ashore. Tsunamis occur occasionally on the West Coast. Coastal flooding related to hurricanes sometimes occurs in Atlantic Canada. Scientists warn that these hurricanes may become more powerful as sea-surface temperatures warm due to climate change.

In general, extreme weather events associated with flooding are likely to increase with climate change, and Canada and other countries may experience even larger and more frequent floods in the future.

How Are Floods Controlled?

A traditional response to flooding has been to attempt to control high flows by building dams, dikes and diversion channels. While there are no comprehensive statistics on national flood damage, some evidence suggests that such engineering works have not prevented a rise in nationwide damage. In many regions, urban and suburban developments for housing, industry and commerce have been located on flood plains, behind dikes or downstream from flood control dams. When extreme, low-probability floods occur, they can overtop the protective works and cause more damage than in the past, as more property lies in the path of flood waters.

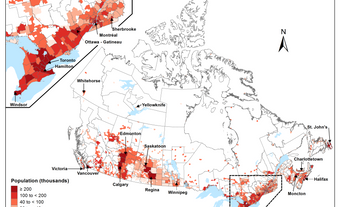

Because of this risk, the federal government invited the provinces to join in a coordinated program to address flood losses in a more comprehensive way. In 1975, it announced a flood damage reduction program, the main result of which was that flood-risk maps were created to identify hazardous areas. The maps, along with flood plain land-use regulations by the provinces and municipalities, were designed to discourage further development. Some 300 locations throughout Canada were mapped and these documents were made available to flood-plain managers, urban planners, property developers and the public.

Provincial and municipal policies, regulations, bylaws and public information activities are based on such maps. Construction of new homes and businesses in these flood zones is discouraged (but not prohibited) in favour of reserving the land for parks and other open spaces, recreation facilities and wildlife habitat. The program has successfully alerted provincial and municipal governments to the need for a more comprehensive approach to reducing flood damage, including flood forecasting and warning systems, emergency measures, structural measures for flood control and land-use planning.

In 1996–97, the federally sponsored program was phased out during a period of fiscal restraint, but the concept of adjusting the location, pattern and type of human settlement to the flood hazard has replaced the concept of simply trying to control floods.

Historic Floods in British Columbia

Several major floods have been recorded in the lower Fraser River valley in British Columbia since the first settlers arrived in the area. The largest occurred in May 1894, when river waters flooded the area between the Harrison River and Richmond due to snowmelt. The second major Lower Fraser flood occurred in the spring of 1948. Damage was more extensive than in 1894, as the area’s population had grown significantly; 16,000 people were evacuated from their homes. Since then, population and development have only increased in the Richmond area. Although Richmond is protected by dikes, the risk of them being overtopped cannot be ruled out.

In 1972, flooding along the Fraser and within its drainage basin incurred $5–10 million in damages. The hardest hit communities were Prince George, Surrey and Kamloops, where the North Thompson River, a tributary of the Fraser, also flooded.

An earthquake off the coast of Alaska in 1964 produced a tsunami that travelled south and struck the British Columbia coast. It moved up Alberni Inlet, concentrating its energy before hitting Port Alberni. The giant waves destroyed boats, homes, cars and infrastructure in the community.

Historic Floods in the Prairies

Alberta and Saskatchewan

Alberta and Saskatchewan were hit with many floods during the 19th and 20th centuries. In Calgary, for example, flooding of the Bow and Elbow rivers has destroyed bridges and railway lines and forced evacuations. Events of this type occurred in the city in 1879, 1902, 1915, 1929 and 1932. The North Saskatchewan River also flooded in 1915, devastating Edmonton ( Alberta) and Prince Albert (Saskatchewan). The Canadian Disaster Database, maintained by Public Safety Canada, lists dozens of other significant floods across these provinces in the 20th century.

Some of the most dramatic and costly Prairie floods occurred more recently. Heavy rainfall in the spring of 2005 caused several rivers to flood in southern Alberta , including the High, Bow, Elbow, Oldman and Red Deer rivers. Over 7,000 people were evacuated from these regions. Costing an estimated $400 million in damages, it was one of the most expensive disasters in the province’s history.

In 2010, the same region of Alberta, along with the southern portions of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, experienced one of the wettest springs and summers on record. Saskatoon, for example, received 645 mm of rain between April and September, breaking a 1923 record of 420 mm. Between Saskatchewan and Alberta, just over 2,000 people were evacuated over the course of the season, according to Public Safety Canada. The excess precipitation made the growing season incredibly challenging for Prairie farmers, with Statistics Canada reporting 15 per cent less wheat harvested than in 2009.

In the spring of 2013, flooding affected the southern quarter of Alberta, including Calgary. As many as 100,000 people evacuated the area when the Bow River watershed experienced above-average spring runoff and rainfall. In addition, four people died of drowning. In Calgary, 3,000 buildings were flooded and infrastructure was destroyed. Estimates of the total cost run as high as $6 billion, and the$1.7 billion paid out by insurers rivals the damages incurred during the ice storm of 1998.

Manitoba

One of Canada’s most flood-prone areas is that of the Red River in Manitoba. Snowmelt waters from the United States flow north through a wide, flat plain (the bed of former glacial Lake Agassiz), and severe flooding can create havoc in many small communities as well as in the city of Winnipeg. Large floods are known to have occurred in 1776, 1826, 1852 and 1861, while the worst floods of the 20th century took place in 1950, 1966, 1979 and 1997.

The 1950 flood inundated many valley towns and one-sixth of Winnipeg in May of that year. More than 100,000 people had to be evacuated. The construction of floodways to carry offspring overflow alleviated the problem around the city; rural areas, however, remained vulnerable.

Three decades later, these floodways were put to the test when, in April and May of 1979, the Red River flooded to within centimetres of the levels seen in 1950. This time, however, Winnipeg was largely unaffected, while over 10,000 people were evacuated from valley communities.

The flood that occurred from mid-April to early May 1997 was named “The Flood of the Century,” though in terms of the amount of water the Red River discharged, it was in fact the largest flood since 1826, almost two centuries earlier. The flooding of more than 1,800 km2 of land resulted in the evacuation of nearly 30,000 Manitobans. Some 7,000 troops were mobilized to assist civil authorities. (See also Red River Flood.)

Historic Floods in Ontario

In October 1954, heavy rains associated with Hurricane Hazel caused flooding on the Don and Humber rivers in Toronto and resulted in more than 80 deaths and severe damage. Since then, much of the damageable property has been removed from the flood plains and restrictions have been placed on their development.

A thunderstorm in Timmins in August 1961 caused Town Creek to flood, destroying roads and homes in the city and killing five people.

In May 1986, flooding on the Winisk River near Hudson Bay destroyed the Weenusk First Nation townsite and killed two people. The community resettled on higher ground in nearby Peawanuck.

The Great Lakes have been hit by major floods when storms and high water levels coincide. Over the years, damages due to shoreline flooding and erosion have incurred hundreds of millions of dollars in damage. The most severe Great Lakes floods occurred in 1952, 1972–73 and 1985–87.

Historic Floods in Quebec

The St. Lawrence River presents a risk of flooding in the winter due to ice jams (i.e., dams created by a natural buildup of ice fragments). Major floods of this type occurred in 1886 and 1965, the first costing Montreal millions of dollars in damages and the second killing five people in communities downstream of the city.

In the spring of 1974, over 300 municipalities were affected by province-wide flooding along the Gatineau, Ottawa, Richelieu, St. Lawrence, Châteauguay, Saint-Maurice and Chaudière rivers. Over 7,000 people had to be evacuated, 3,000 of whom were from Maniwaki.

Heavy rain from thunderstorms in Montreal in July 1987 created a flash flood that cut off power to much of the city, flooded at least 40,000 homes and killed two people.

The Saguenay region of Quebec experienced severe flooding on 20–21 July 1996. An intense summer storm, combined with inadequate storage capacity of some dams, led to floods throughout the region. The damage was severe because houses and other developments had been constructed on lands that were assumed to be protected against such events. Some 16,000 people were evacuated temporarily; 10 were killed. (See also Saguenay Floods Kill 10; Saguenay River.)

Historic Floods in the Atlantic Provinces

New Brunswick

Records of flooding in New Brunswick date back as early as 1696. Many of the province’s most significant floods have occurred in the Saint John River basin, typically because of snowmelt, ice jams and heavy rain.

In 1902, 15 ice jams in the Saint John River basin caused severe floods that killed two people in addition to damaging transportation infrastructure and sawmills. In 1936, flooding from 22 ice jams caused even more widespread damage at a cost of approximately $2 million.

The village of Perth-Andover was at the centre of major floods on the Saint John River in 1976 and 1987. A state of emergency was called; homes and several public institutions were evacuated. A rail bridge in the community survived the high waters of the 1976 flood but collapsed in the 1987 event.

New Brunswick has been affected by flooding related to several extreme weather events: Hurricanes Edna (1954), Gladys (1968) and Belle (1976), as well as Tropical Storm David (1979) (see also Hurricanes).

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia’s first flood on record hit Halifax in 1759, the result of a storm on the Bay of Fundy. Many of the province’s subsequent floods have owed to a combination of snowmelt, heavy rain and ice jams. In January 1956, for example, a long period of thaw due to warm temperatures inundated waterways and created ice jams. Flooding occurred provincewide, destroying more than 100 bridges.

Nova Scotia has also been hit by flooding related to hurricanes and tropical storms. Among the most severe were Hurricane Beth in August 1971 and the “Groundhog Day Storm” in February 1976. Flood damage primarily occurred in coastal areas of the province at a combined cost of more than $12 million.

Newfoundland and Labrador

In northern areas of Newfoundland and Labrador, where snow usually remains frozen winterlong, river basins tend to flood in the spring. In central and southern Newfoundland, however, flooding is a year-round phenomenon that owes to a combination of rainfall, snowmelt and ice jams.

Coastal areas of the province have been affected by floods related to storm activity. Among the first floods recorded in Newfoundland and Labrador is a 1755 event that swamped the community of Bonavista; this was likely the result of a tsunami generated by a massive earthquake near Lisbon, Portugal. In 1885,large waves damaged coastal areas of northern Labrador during a period of sustained high winds known as the Great Labrador Gale. The storm took many lives, but it is unclear whether the flood itself caused any deaths. The Avalon Peninsula in southeast Newfoundland is among the most frequently affected coastal areas, the town of Placentia having recorded several floods dating back to 1904.

On 18 November 1929, a tsunami hit the Burin Peninsula, destroying many structures and killing 27 people. Because of the island of Newfoundland’s sparse communications networks and the damage done to existing lines, news of the disaster did not reach mainland Canada until three days later.

In January 1983, in the Exploits River basin in central Newfoundland, flooding from a rainstorm combined with snowmelt from warm temperatures damaged property to the tune of approximately $34 million.

Prince Edward Island

With its smaller rivers, Prince Edward Island does not experience the degree of watershed flooding seen in other provinces. Nevertheless, floods due to heavy rainfall and snowmelt do occur in PEI. In April 1962, for example, a heavy rainstorm hit PEI’s snow-laden south coast. Highways and bridges were washed out, and damage totalled about $300,000. Severe rainstorms in September 1999 and March 2003 also damaged infrastructure and property at an estimated cost of $1.4 and $2.4 million respectively.

Coastal flooding is a special concern in PEI. Studies commissioned by Natural Resources Canada and the Charlottetown Area Development Corporation (published in 2014 and 2016 respectively) have assessed how Charlottetown may be impacted by rising sea levels due to climate change.

Historic Floods in the North

Yukon

In Yukon, most floods occur in spring due to snowmelt and rain. Ice-jam flooding is also common when ice forms in winter and breaks up in spring, especially along the Yukon River, affecting Dawson City and Whitehorse. In May 1979, 80 per cent of buildings in Dawson City were flooded by an ice jam on the Yukon River, at a cost of approximately $1.85 million. In June 2012, a combination of rain and snowmelt flooded Upper Liard, Yukon, as well as areas of northern BC and western Northwest Territories. Total damage was estimated at $1.5million.

Northwest Territories

Ice jams from spring breakup are also a primary cause of flooding in the Northwest Territories, while summer floods result from glacial melt and rain in the Mackenzie Mountains. Both of these types of flooding affect communities in the vast Mackenzie River basin. In early May 1989, ice jams caused flooding on the Liard River, incurring $1.1 million in damage to the area around the hamlet of Fort Liard and the town of Hay River, in the south of the territory. On 27 May 2006, the hamlet of Aklavik in the Mackenzie River delta was flooded by ice melt from the Peel Channel. Damage to homes and infrastructure totalled approximately $3.1 million.

Nunavut

Pangnirtung, on Baffin Island, was the site of the one major flood to affect Nunavut since it was created out of the eastern portion of the Northwest Territories in 1999. The community was inundated by heavy rains on 8 and 9 June 2008. Combined with snowmelt, the rain cut deep channels in permafrost and eroded the foundations of two bridges. Roads and municipal water services were damaged, and the total cost of the flood was nearly $5 million.

In July 2016, Iqaluit was hit with record rainfall that flooded parts of the city.

In the 21st century, Nunavut may see an increase in coastal flooding as sea levels rise due to climate change.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom