Fishes are members of a large, heterogeneous group of vertebrates living in a wide variety of aquatic habitats. There are slightly more species of fishes than of all other vertebrates combined. About 1,200 species of native fishes are found in Canadian waters, the majority of which (990) live in marine waters.

Description

Fishes include jawless species (Agnathans), such as hagfishes and lampreys, and species with jaws (Gnathostomata).

Gnathostomes comprise five major lineages: the extinct Placodermi and Acanthodii, and the living Chondrichthyes, Actinopterygii and Sarcopterygii.

Chondrichthyes are cartilaginous fishes and include sharks and rays.

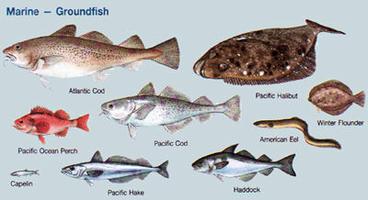

Actinopterygii are ray-finned fishes, for example, salmon, perch and flatfishes.

Sarcopterygii, lobe-finned fishes, include coelacanths and lungfishes, as well as tetrapods, since some tetrapods (i.e. animals with four feet or limbs) are thought to have evolved from sarcopterygian fishes.

The term "fishes" is used by some ichthyologists (i.e. zoologists who study fish) in a more restricted sense than used here. Some would include only forms with jaws. As the term is used here, fishes may be defined as cold-blooded vertebrates with gills throughout life, and limbs, if any, in the shape of fins. Most have scales and paired fins; however, many unrelated groups lack scales (e.g., lampreys, North American catfishes) or one or both of the paired fins (e.g., lampreys, eels, most sand lances). In terms of plural versus singular usage, the term "fishes" is properly used in reference to individuals of more than one species. However, in reference to one or more individuals of only one species, the term "fish" is appropriate.

Form and Colour

Fishes exhibit a wide variety of shapes, sizes and colours. They range from long, almost string-like lengths, to globular forms. They can look like a lumpy rock, a leaf or a snake. Most have a tapering, variably compressed body with smooth contours, exemplified by trout.

Fishes range in size from a whale shark, exceeding 12 m, to a tiny, 8-10 mm minnow, goby or schindleriid. In Canadian waters, the smallest fishes (e.g., some minnows, darters, sculpins) may not exceed 10 cm, while those over 3 m include Atlantic sturgeon and bluefin tuna. Several may even exceed 5 m (e.g., white sturgeon, thresher, white and basking sharks).

Fishes are highly variable in colour. In the tropics, there are many brilliantly coloured freshwater and marine fishes, but those in Canadian waters, as in other northern areas, are generally drab. There are some exceptions, however, and males of several species can develop bright colours at spawning time (e.g. Arctic char, sockeye salmon, northern redbelly dace, longnose sucker, some darters). There tends to be more variation in colour among populations of the same species of northern freshwater fishes than among tropical fishes. The marked colour variations of rainbow trout or northern pike have erroneously convinced some anglers that there are different species of these fishes in different localities.

Scales

Sharks and rays have placoid scales resembling tiny teeth. Most species of bony fishes with scales have either cycloid scales (smooth bordered) or ctenoid scales (rough bordered). Teleosts, the largest and most recently evolved group of bony fishes, display both forms of scales: cycloid scales characterize relatively primitive teleosts (e.g., salmon, minnows); ctenoid scales characterize advanced teleosts (e.g., perch, sunfishes).

Generally, fishes with cycloid scales have pelvic fins in the mid-portion of their bodies and lack spines in the fins; those with ctenoid scales have pelvic fins beneath the pectoral fin and have spines in some of their fins. Although frequently used to tell a fish's age, scales are not always reliable; certain bones in the head may be more accurate.

Buoyancy and Respiration

Most bony fishes possess a swim or air bladder that helps them attain neutral buoyancy in water. Many bottom fishes lack the bladder, enabling them to stay on the bottom, even in relatively fast streams, with minimum energy expenditure. Some species (e.g., longnose dace) can change bladder volume over relatively short periods of time, increasing it when in a lake, decreasing it in a river.

Although a few fishes have lungs or other organs for breathing air, all fishes possess gills. In Canada, fishes are virtually always confined to water for respiration, but elsewhere there are species that can breathe in the atmosphere and even make journeys onto land.

Distribution and Habitat

Canada has a diverse group of living fish species, including representatives of most classes. This fauna is rich in numbers of individuals, but not in numbers of species, especially when the vast amount of freshwater lakes and rivers and the extensive coastline are considered. There are about 28,000 recognized species of living fishes worldwide, comprising about 515 families. About 43 per cent of these species live in fresh water. Roughly 1,200 species of native fishes in about 195 families live in Canadian waters.

Of this number, about 990 are confined to marine waters (Pacific, Arctic and Atlantic oceans). Several species are diadromous, meaning they spend part of their life in the ocean and part in fresh water. Of these, some (Pacific salmon, many lampreys) are anadromous, spawning in fresh water, while the American eel of the Atlantic coast is catadromous, spawning in the ocean.

The native species confined to fresh water (about 180) occur in drainages of the Pacific, Arctic and Atlantic oceans, Hudson Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. The Great Lakes and southern Ontario have the greatest number of species; the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Alberta and Saskatchewan have relatively few, considering their area and extent of water.

In marine and fresh water, various species can be characterized as bottom dwelling (i.e. benthic) or open water dwelling (i.e. pelagic). Littoral zone fishes are inshore and, in oceans, may occur in tide pools. In the Arctic Ocean and Arctic lakes, fishes may spend most of their lives under ice. There waters can be colder than -1°C.

Freshwater habitats of fishes are diverse, including hot springs, cold torrential mountain streams, deep lakes and saline waters. In the Cave and Basin Hot Springs drainage system near Banff, Alberta, individuals of a few species such as longnose dace, normally found in cold lakes and streams, occasionally move in from the Bow River and live in temperatures up to 26ºC and in close proximity to introduced tropical aquarium fishes (e.g., sailfin molly and mosquito-fish, which live in temperatures of up to 30ºC). In Wood Buffalo National Park, fishes live in sinkhole lakes, formed by the surface collapsing through dissolved-out bedrock. In some cases, they arrived at the small ponds via underground channels.

Diet

Fishes consume a wide variety of foods. Northern fishes have more generalized feeding habits than tropical fishes, and tend to eat what is available. Most species are carnivorous; some are herbivorous, usually consuming algae. The latter tend to have longer intestines. Many species are primarily bottom feeders (e.g., sturgeons, suckers); others feed on plankton in open water (e.g., herring, cisco). Piscivorous fishes (e.g., northern pike) feed primarily on other fishes. Insects and crustaceans are generally the most important diet items for non-piscivorous, freshwater species in Canadian waters. The lamprey is the only parasitic-like northern fish; adults of many species feed on the blood of other fishes.

Reproduction

Reproductive habits vary greatly. Chondrichthyes have internal fertilization; most Actinopterygii have external fertilization. In Canadian waters, most Actinopterygii have distinct spawning seasons. Eggs laid in fresh water by fall-spawning fish generally hatch in spring; those laid in summer hatch in a few days or weeks. Some (e.g., sticklebacks, sunfish) build nests in which eggs are deposited and sometimes guarded.

Herring and cod abandon their eggs after spawning. Individuals of most species can spawn for several years, but lampreys and Pacific salmon spawn once and die. Many species migrate great distances to reach spawning grounds. One of the longest migrations is made by Chinook salmon, which swim, without feeding, for about 2,800 km up the Yukon River.

Evolution

Fishes probably shared a common ancestry with cephalochordates (small eel-like burrowing marine animals) and in turn gave rise to amphibians. Their origin dates back to about 530 million years ago. In Canada, there is an extensive fossil record of fishes, including Agnathans, Chondrichthyes and Actinopterygii. Placoderms and acanthodians are two other large groups known only from the fossil record.

The ice ages had a profound effect on Canada's fish fauna. Differences in species numbers across Canada can be explained by glacial events. Until about 18,000 years ago, most of Canada was covered by ice. A reinvasion of fishes occurred from ice-free areas, with most of our modern freshwater fish coming from the Mississippi-Missouri refugium (i.e. a place where organisms can survive unfavourable conditions). Most of British Columbia's species came from the Columbian River refugium; in other areas of Canada, the Yukon River and Atlantic coast refugia were important. As the ice sheet melted, species could cross from one drainage basin to another, eg, from the Columbia River to the Fraser River. Only fishes with some salt tolerance could reach offshore areas (e.g. Newfoundland and Labrador, Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii).

More new species of fishes are described each year around the world than species of any other vertebrate group. It is unlikely that many species new to science will be found in Canadian waters (although range extensions may continue to be found). Few species appear to be confined to Canadian waters. A species of whitefish (Coregonus huntsmani, the Atlantic whitefish), confined to a part of Nova Scotia, has been described, but its existence may be threatened by acid rain.

Although biologists in provincial and federal government agencies, universities and consulting companies are involved in fish studies, many gaps remain in our knowledge, especially of the life history of many commercially important species (e.g., very little is known about habitats of larval herring and lake whitefish). Collecting trips often reveal a species not previously recorded in a particular province or even in Canada, particularly off the Pacific coast. Observant fishermen, interested in identifying their catch, can provide valuable distributional records.

See also Atlantic salmon; bass; chimaera; gar; grayling; mackerel;muskellunge; pickerel; scorpionfish; smelt; sportfishing.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom