This article was originally published in Maclean's Magazine on March 20, 2000

Employment Rises

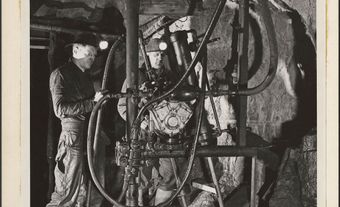

John Jacobsen has been through a lot of boom and bust cycles over the past 30 years, but he's never seen anything quite like this. As vice-president in charge of operations for Calgary contractor Precision Drilling Corp., Jacobsen has to move fast when oil prices rise and the demand for drilling crews shoots upward. Right now, Precision has 206 rigs, each staffed by three five-man crews, running flat out - up from 139 rigs a year ago - and the company is still short about 20 crews. There are plenty of applications from inexperienced workers: Precision has 2,000 on file and isn't taking anymore right now. But finding staff who know what they are doing is devilishly tough. Precision's personnel staff are working 12-hour days trying to find people, even though the pay for drillers is good: about $26 an hour for someone with equipment know-how. "This upturn is quicker than I've seen in the past," Jacobsen says. "These cycles are part of our business and you learn to live with it, but it does slow us down when we have to compete with other industries, like construction."

Finally, the turnaround is here. After almost a decade of painfully high unemployment, skilled Canadian workers are in big demand. In December, the unemployment rate hit a 24-year low of 6.8 per cent, which it maintained through January and again when February's numbers came out last Friday. Each month, Statistics Canada said the rate would have been even lower if tens of thousands of formerly discouraged workers had not resumed looking for work. More than 44,000 new jobs were created in January, with another 36,000 added last month. Ontario has been one of the biggest job creators, but British Columbia is also on the comeback trail. Cities like Montreal, once plagued by bad times, are also showing strong labour-market growth. January's surge included 39,000 positions in health care and social services, while almost all of February's gains were due to new full-time jobs in the private sector, where rising prices for commodities and robust consumer spending are fuelling continued economic expansion. "We're finally catching up after a very difficult decade," notes Peter Drake, vice-president and deputy chief economist at the Toronto Dominion Bank. "Nothing is ever guaranteed, but there are lots of reasons to think this is a solid recovery for the labour market."

Jobs are sprouting in almost every area where skilled labour is required, including the public sector, private business and the ranks of the self-employed: half of January's gains were among those starting up new businesses. Deborah Kudzman, 31, is one new entrepreneur who took advantage of improving economic conditions to risk setting up on her own. A Montreal advertising account executive who has worked in marketing for eight years, Kudzman went into business with a partner last November, 11 months after giving birth to her first child, and has already landed lucrative accounts in the financial and pharmaceutical industries. She has been so busy, she has not had time to order letterhead for the company, Publicité Piranha. "I always wanted to have my own agency and it was clear things were improving in Montreal," Kudzman says. "If you have the experience and you think you can do it better than someone else, you probably can."

Good times are also making it easier for employed workers to move into better jobs. Rosi Petkova has been a graphic designer for 14 years, the past three in Vancouver, where she worked as a freelancer for the company that publishes The Yellow Pages. She has always been able to find work, but she could hardly believe it when her job search last fall yielded seven interviews in one week. She finally whittled the choices down to three: a full-time job at The Yellow Pages, another at B.C. Gas Inc., and the Vancouver Film School, which offered the same money as the others but a more stimulating environment. After taking a couple of days in the mountains to think about it, she chose the film school. "Here, there is enough space for your imagination," says Petkova, 41. "They want you to do what you love and that is very motivational - it's what brings me to work every day."

Competition for high-tech workers is especially fierce. Alexei Domratchev, 25, started working for Hummingbird Communications, a Toronto software development firm, only a few months after arriving from Russia. He had other offers but chose Hummingbird, he says, because of its size and strong reputation in his field of expertise, Web applications development. Money was not crucial to his decision, he says, although Hummingbird offered him more than he asked for. "I wanted to be at a company that is on the leading edge," he says.

This seller's market has a lot of employers scrambling. Salaries are rising and signing bonuses are becoming more common, especially in high-tech industries competing for top performers. Some companies, too, are offering perks like on-site lounges and exercise facilities, flexible hours and even three- or four-day work weeks, with no downside when it comes to promotion or raises. Paul Crath, a senior vice-president with the executive search arm of Toronto-based management consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, has been helping companies find executives for about 20 years and says candidates definitely hold more of the bargaining chips these days. As a result, many companies are working far harder to get - and keep - key personnel. "Employers are becoming very conscious of their reputation and whether they are seen as a good place to work," Crath says, noting that pay and opportunities for advancement remain top priorities for most executives. And quite often, hiring is not the end of the story. "Even when the person is happy," Crath adds, "employers have to be aware that they could lose them to someone else who taps them on the shoulder six months later."

George Cwynar, president and CEO for Kanata, Ont., semiconductor provider Mosaid Technologies Inc., agrees that finding the best people has become much tougher, especially over the past six months or so. In that period, the 200-employee company has hired about 35 new staff, including engineers, sales and marketing personnel, and people who oversee operations and manufacturing. Currently, Mosaid is looking to fill 30 or 40 more positions. Cwynar says the company is proud of the extras it offers, such as an attractive office complex that includes a converted heritage home, a park-like setting, a lounge for employees and a pool room. But like many other firms, Mosaid is facing increasingly stiff foreign competition. "The rest of the world has discovered that Canada has some very talented people," Cwynar says. "They are being lured to the U.S., as well as to U.S. branch plants that are setting up here and offering compensation on a par with their parent companies."

For the moment, things are certainly looking good for Canadians with marketable skills. And as the TD Bank's Drake notes, many forecasters believe Canada will lead the Group of Seven countries this year, with an economic growth rate of close to four per cent. But good times have been a long time coming and they won't go on forever. Gilles Rheaume, vice-president of innovation and regulatory affairs for the Ottawa-based Conference Board of Canada, notes that Canada still lags badly behind many other industrialized nations when it comes to research and development, as well as investing in new equipment and innovative technologies - key factors in developing a recession-resistant economy. And if the dollar appreciates strongly, or if the economy of Canada's largest trading partner - the United States - slumps, or commodity prices fall, watch out. The time for employees to take advantage of a tight labour market is right now, he says, adding wryly, "then hope for the best." If the economy stays on track, though, the best may be yet to come.

Lowest in a Generation

The Montreal Olympics had not even opened the last time the national unemployment rate was so low. The current rate of 6.8 per cent was last matched in April, 1976.

February, by province:

B.C.: 7%; Alberta: 4.9; Saskatchewan: 4.6; Manitoba: 5.3; Ontario: 5.7; Quebec: 8.3; New Brunswick: 9.7; P.E.I.: 11.5; Nova Scotia: 9.7; Newfoundland: 17.6

Source: Statistics Canada

Maclean's March 20, 2000

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom