Dance is the term broadly used to define a human behaviour characterized by movements of the body that are expressive rather than purely functional. But in some circumstances, pedestrian movements such as walking, crawling, running and jumping can be described as dance activity. It is the social, cultural, philosophical, spiritual, religious, emotional and intellectual motivation that distinguishes dance from purely functional movement. Because dance is a cultural expression, what constitutes dance is culturally relative, and diverse manifestations of dance abound throughout the world. Dancing itself also arises in a variety of environments, be it on the proscenium stage, in folk settings, on film, or in site-specific work. These characteristics can, then, be applied to Canadian dance.

Dance is an ancient human practice which might have begun as an instinctive response to such naturally occurring cycles as night and day and the beat of the human heart. This perhaps explains why dance often has a rhythmic basis, according to context. Dance arose from the same impulses that gave birth to music and, while dance is often though not invariably accompanied by music, it remains unclear which expression came first. As long as people have inhabited the land we now call Canada, there has also been dance, or organized movement, as a form of human cultural expression.

Long before the arrival of transatlantic explorers, dance was an important part of the ritual, religious and social lives of Canada's Aboriginal peoples. The earliest written record of dancing in Canada is found in the diaries of Jacques Cartier, who wrote in 1534 of being approached, along the shore of Chalem Bay, by seven canoes bearing "wild men ... dancing and making many signs of joy and mirth." In their journals, those who came after Cartier made frequent reference to multiple Aboriginal forms of dance, but with muted cultural understanding of what these dances represented to the Indigenous peoples in question.

Under the impact of centuries of colonization and immigration, Canada's Indigenous peoples retained only a tenuous hold on their once rich dance heritage. Given the often hostile indifference of European settlers to the Aboriginal cultures they disrupted and displaced, and the very different directions in which dance developed in the settler cultures, it was inevitable that Aboriginal dance forms would struggle to have an impact on the later development of dance in French or English Canada. Indeed, Aboriginal dance forms were silenced by colonizers; for example, the Canadian government restricted the practice of the Potlatch, a ceremony comprised of two dance series practiced by the Kwakwaka'wakw in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; laws prohibiting its practice were created in an effort to quash First Nations culture and assimilate community members into Western practices. However, by the end of the 20th century, the established and evolving tradition of Indigenous dance performance emerged as an important element of the culture of many of Canada's Aboriginal communities, as was an investment in reclaiming and revitalizing First Nations dance for future audiences. Contemporary First Nations dance artists have continued to explore the roots of Aboriginal dance forms via contemporary and ballet-based choreography, while at once invigorating traditional folkloric stories and engaging with First Nations communities in order to provide diverse perspectives on their own histories, all the while maintaining a tradition once endangered by colonial policy in Canada. Such artists include Santee Smith and her company Kaha:wi Dance Theatre (Ontario), and Raven Spirit Dance (British Columbia). Even in the context of a ballet, Canadian dance has tackled First Nations issues; The Royal Winnipeg Ballet's Going Home Star — Truth and Reconciliation (2014), choreographed by Mark Godden and based on a story by Joseph Boyden, explores the dark atrocities made against Canada's Aboriginal peoples, including their confinement and abuse in residential schools.

During the 20th century, non-Aboriginal choreographers occasionally attempted to create dances derived from or inspired by Aboriginal folklore and movement forms. At best, these efforts tended to be little more than well-intentioned parody and at worst, inherently problematic and easily construed as racist. It was only in the later years of the last century, as the centrality of a European-based culture gave way to a more pluralistic, multicultural view of Canadian society, that a handful of mainstream modern choreographers began to approach Aboriginal dance forms with an attitude of genuine humility and respect. Various efforts in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century have also been undertaken particularly in British Columbia, by dance companies such as the Karen Jamieson Dance Company, but also elsewhere, to explore the potential interaction of Aboriginal dance traditions with non-Indigenous forms in French and English Canada.

Imported Dance Influences

The phenomenon of dance as performance has a long history and arose when particular sequences of movement became too complex for everyone in a community to learn, or were reserved for a privileged few. It became customary for some to dance and others to watch. In Europe, where by the 18th century dance had largely relinquished its religious and ritual functions and evolved into a form of entertainment, a further distinction arose between increasingly professionalized theatrical dancing and dance in all its other manifestations. It is a distinction that persists and is fully reflected in the way dance has evolved in Canada.

The modern history of dance in Canada begins with the implanting of European culture from the 16th century onward. In both its theatrical and social dimensions, dance in Canada has reflected the traditions of its immigrant cultures. Although born in the courts of Renaissance Italy, classical ballet, as we know it, took shape in France and quickly became popular across Europe. It was thus natural for Canada's French settlers to enjoy ballet. There are isolated instances of rudimentary performances, often pageants or masques that included drama and music, occurring in New France during the 17th century. As the art became more sophisticated and technically evolved, performances by itinerant troupes of dancers also became popular.

The French, and later the British, brought with them their own social dances and movement rituals but, despite the presence from the mid-18th century of local dancing teachers in Canada's principal colonial settlements, theatrical presentations of dance were generally imported. This certainly continued into the 20th century, as immigrants from multiple continents transplanted themselves and created new work in the continually diversifying Canada, particularly in major city centres like Toronto, Montréal, and Vancouver. While some continued to practice established traditions, others created contemporary, fusion work which was an amalgamation of older and newer movement vocabulary, and embraced a wide scope of cultural influences. Vancouver-based Kokoro Dance, co-founded by Barbara Bourget and Jay Hirabayashi, is an example of a company whose aesthetic and choreographic output are influenced by ballet, jazz, modern dance, dance theatre, and the modern Japanese dance form known as butoh. The work of mid-career and emerging dance collectives in Vancouver, such as The Plastic Orchid Factory, The Tomorrow Collective, The 605 Collective, Move: The Company, and others also straddle a variety of movement practices from hip hop, to ballet, to martial arts, to theatre, and transplant the work in theatres and in outdoor settings. The embracing of multiple genres signals the interest on the part of Canadian dancers to innovate in choreography and performance, and also suggests an open-mindedness towards broadening an audience’s understanding of what constitutes dance inside and outside of the theatrical setting.

The Development of Professional Ballet in Canada

Louis Renault, with a studio in Montréal from 1737 to 1749, was among the first known ballet teachers in Canada. In a 1749 letter from Montréal, an aristocratic Frenchwoman noted the enormous local enthusiasm for dancing. She observed that it continued unabated in the face of the clergy's serious opposition, which was to endure in French Canada until the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s.

The British Conquest of 1760 did little to dull the local appetite for dance. John Durang, a versatile entertainer widely credited as America's first professional dancer, appeared with a circus troupe in Montréal and Québec City during the winter of 1797-98. Writing in the early 1800s, the Englishman George Heriot observed: "The whole of the Canadian inhabitants are remarkably fond of dancing." In 1816, a performance of La fille mal gardée, created in Bordeaux in 1789 and still one of ballet's most enduringly popular comic creations, was given in Québec City. Celeste Keppler, a famous French dancer, made several Canadian appearances during the 1820s and '30s.

A pattern was established. Canada's immigrant population amused itself with the social dances it had packed in its cultural baggage, yet was generally content to hire its professional dance entertainment from abroad. With its close proximity to the United States, Canada became an integral part of the North American touring circuit. As a network of railroads spread across the country, it became easier for touring ensembles to penetrate the interior. Serge Diaghilev's Ballet Russe, with its legendary star Valslav Nijinski, made its only Canadian appearance in Vancouver in 1917, but the company's various namesake successor troupes became popular attractions across the country. Arnold Spohr, later to become a central figure in the development of Canadian ballet, was inspired to become a dancer after attending a performance of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in Winnipeg in 1942. During the first half of the 20th century, audiences had the opportunity to see such celebrated Russian ballet stars as Anna Pavlova, Léonide Massine and Alexandra Danilova. There were also visits by Loie Fuller, Ruth St. Denis, Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham, all pioneering exponents of the new Modern Dance, or "barefoot ballet" as it was disparagingly dubbed by traditionalists. Even so, although a small but dedicated audience of dance aficionados was emerging, the immediate prospects for professional theatrical dance in Canada remained unpromising. The foundations of professional dance, however, were slowly being laid by a number of gifted immigrant ballet teachers, notably Americans June Roper in Vancouver and Gwendolyn Osborne in Ottawa, and the Russian émigré, Boris Volkoff, in Toronto.

After a successful stage career, Roper taught in Vancouver from 1934 to 1940. She was a fine pedagogue. Many of her school's more than 70 graduates enjoyed later careers in musicals and reviews and about a dozen emerged as fully fledged classical ballet dancers. Eight of these were accepted into major American-based troupes. Scottish-born Ian Gibson, later hailed as Canada's Nijinsky and briefly a star of New York's Ballet Theatre, was among Roper's pupils. Since audiences of that era had come to associate Russia with the highest standards in ballet, it was not uncommon for Western dancers to adopt Russianized names. Manitoban Rosemary Deveson and British Columbian Patricia Meyers, both students of Roper, became respectively Natasha Sobinova and Alexandra Denisova with de Basil's Ballet Russe company.

Volkoff, born in Schepotievo in 1900, was authentically Russian. He arrived in Toronto in 1929 and initially staged dance numbers to be performed between movies at producer and conductor Jack Arthur's Uptown Theatre. In 1931 Volkoff opened his own school and in 1936 adventurously took a group of students to the Internationale Tanzwettspiele of the Berlin Olympics, performing his works inspired by Aboriginal legends. In 1939 the Volkoff Canadian Ballet made its formal debut, vying for the legitimate title of first Canadian ballet company with a little group in Winnipeg, established almost at the same time by recent English immigrants Gweneth Lloyd and Betty Farrally.

Both companies, professional in ambition but essentially amateur, struggled to stay afloat through the war years. In 1948 they came together in Winnipeg, along with Polish-German immigrant Ruth Sorel's modern troupe from Montréal, for the first in a series of six catalytic Canadian ballet festivals. The second, held in Toronto, combined with a visit the same year by the British Sadler's Wells Ballet, spurred a local group of balletomanes to dream of a "national" company. The growing popularity and success of the Winnipeg Ballet fuelled a spirit of civic competitiveness among the Torontonians, but it required the artistic and leadership skills of invited English immigrant dancerand choreographer Celia Franca to realize their dream. Her Canadian National Ballet - soon renamed, without any official public mandate, the National Ballet of Canada- made its debut in November 1951, much to the consternation of the Winnipeg Ballet. The smaller Prairie troupe, having turned fully professional in 1949, regarded itself as Canada's premier ballet company, a position it boldly reasserted in its successful application for the right to add "Royal" to its name. In 1953 the company was officially retitled the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

In 1952, dancer Ludmilla Chiriaeff, born to a highly cultivated Russian family in Latvia but raised in Berlin, settled in Montréal and soon found work choreographing for the new local Société Radio-Canada television service. Les Ballets Chiriaeff (which was choreographed by Chiriaeff) made its public debut in 1954, was a major hit at the 1956 Montreal Festival, and in 1958 was professionally reconstituted for the stage as Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. Skeptics derisively noted that the troupe was neither grand nor notably Canadian, but Chiriaeff survived to disprove them all, the company continuing to produce acclaimed works.

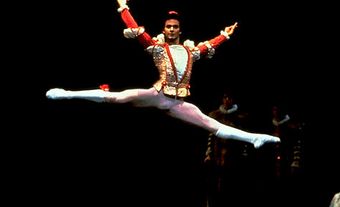

Each of these ballet companies developed a distinct character, an amalgam of artistic ideals and a pragmatic understanding of audience tastes and expectations. Under Spohr's direction, 1958-88, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet built on the populist foundations of its founders. With rarely more than 26 dancers, it remained compact and mobile, and became known for its generally accessible "mixed bills" - programs of works spanning a variety of dance styles and themes, from classical ballet to jazz, from abstract dance to comic narrative works. The Royal Winnipeg Ballet blossomed under Spohr, who worked his dancers hard to improve their performing ability while supplying them with often challenging repertoire. Spohr was tireless in seeking out interesting young choreographers, several of whom, notably Brian MacDonald and Norbert Vesak, were Canadian. Their creations helped give the company a distinctive repertoire and made it very attractive to presenters at home and abroad. In 1965, the trail-blazing Royal Winnipeg Ballet became the first Canadian dance company to perform in London. Three years later it toured triumphantly to Paris, Leningrad and Moscow. In 1972, it toured Australia, and later to South America and Asia.

While in London, Celia Franca had been part of a progressive movement in British ballet. Her own choreography was considered innovative. Some argued that she would have liked to pursue this more adventurous artistic direction in Canada. Instead, Franca shaped the National Ballet of Canada after the model of her former company, the Sadler's Wells (later Royal) Ballet, offering full-length versions of the traditional classics along with mixed programs of 20th-century masterworks. Franca was sometimes accused of neglecting Canadian choreographers, although under her regime, 1951-74, several Canadians were given opportunities. Grant Strate, the most notable of these, was named the company's first resident choreographer. Under Franca the National Ballet of Canada toured Europe and across Canada and the United States. Almost bankrupting the company, the arrival in 1972 of the celebrated Soviet defector and superstar, Rudolf Nureyev, to stage and perform in his opulent version of The Sleeping Beauty, catapulted the company into the international limelight. It also significantly boosted the careers of such young company dancers as Veronica Tennant, Karen Kain and Frank Augustyn.

Until her 1974 retirement as Les Grands Ballets Canadiens' artistic director, Chiriaeff pursued an eclectic vision, generally eschewing tradition in favour of creating a distinctive repertoire from the ground up. Under Chiriaeff, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens began to accumulate a sizable collection of works by the great Russian-American choreographer George Balanchine. The return to Canada of choreographer Fernand Nault, who joined the company in 1965, together with the choreographic contributions of Brian Macdonald, who succeeded Chiriaeff as director, 1974-77, gave the company a distinctly Canadian character. Nault's restaging for Montréal's Expo '67 of his 1962 Carmina Burana, followed by his 1970 rock ballet adaptation of The Who's Tommy, provided Les Grands Ballets Canadiens with two of its greatest hits.

These three large ballet companies in Winnipeg, Toronto and Montréal, together with the professional schools they spawned, constituted the bedrock of Canadian professional ballet upon which, with crucial funding from the Canada Council for the Arts, a diverse professional ballet culture was subsequently built.

The Professionalism of Canadian Modern Dance

By the mid-1960s, professional ballet had been supplemented by the emergence of modern troupes such as Montréal's Le Groupe de la Place Royale, Winnipeg's Contemporary Dancers and the Toronto Dance Theatre. Like the big ballet companies, they assumed an educational function. Together they contributed to a remarkable flowering of dance in Canada, coinciding with an intense period of international interest in the art form - the so-called "dance boom" - and with a new social climate in Canada.

The 1960s, a time of social and intellectual liberalization in much of the Western world, had broken the tight bond between modern Canada and its prim past. The art form of the body attracted new, more receptive audiences, new practitioners and new acceptability. The availability of public funding at the federal and increasingly at the provincial level also created opportunities and helped foster explosive growth in Canadian theatrical dance. Choreographers found the freedom to create works in which form was content; the non-literal and the abstract won a slowly widening respect.

By the time professional ballet companies emerged in Canada, the first wave of the modern-dance movement, itself largely an attempt to rescue dance from what was seen as ballet's rigid academism, was already at a mature stage in its evolution. As in the case of ballet, Canadians initially looked to external influences - European and American - for modernist guidance and inspiration.

Elizabeth Leese and Ruth Sorel, both exponents of the German school of modern dance, opened studios in Montréal in the early 1940s. Their work paved the way for Montréal dance artists who emerged during the cultural revitalization triggered by the 1948 publication of the Refus Global. This was a rebellious manifesto arguing artistic emancipation from the strictures of church and state, and helped make the city fertile soil for innovations in dance.

Three of Montréal's modern-dance pioneers, Françoise Sullivan, Jeanne Renaud and Françoise Riopelle, were associated with the Refus Global movement. Sullivan spent several years as a choreographer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, turned to sculpture and painting, and returned to choreography in the late 1970s, establishing a company of her own and passing on her surrealist influences to a new generation of Québec choreographers. In 1962, Renaud and Riopelle, after spending several years in Paris, founded a Montréal-based modern-dance group which, in 1966, under Renaud and Peter Boneham, a dancer from New York, became Le Groupe de la Place Royale. The troupe developed a reputation as one of the country's most audacious dance experimenters and, since its move to Ottawa in 1977, has continued as an incubator of innovative choreographic talent in Canada.

In Toronto, Bianca Rogge and Yone Kvietys, both from Eastern Europe, were pioneering exponents of modern dance. In the early 1960s, one of Leese's former students, Nancy Lima Dent, joined with Rogge and Kvietys to produce Canada's first modern-dance festivals. Later, Judy Jarvis, a Canadian student of Rogge, studied in Germany with the great modern-dance pioneer, Mary Wigman. On her return to Toronto Jarvis opened her own company which, through the 1970s, passed on the principles of the European school.

American modern dance began to exert its influence in the mid-1960s when Patricia Beatty, who had studied in New York with Martha Graham and danced with Pearl Lang, returned to Toronto and founded the New Dance Group of Canada. In 1968 Beatty collapsed her company into the newly formed Toronto Dance Theatre, to be co-directed by David Earle, a Canadian student of Graham; Peter Randazzo, an American who had danced in Graham's company; and herself. Meanwhile, Rachel Browne, an American-born dancer who performed for several seasons with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, recreated herself as a modernist, largely in the American tradition. By 1965 she had founded Winnipeg's Contemporary Dancers as a modern-dance repertory troupe performing her own works as well as those of a variety of prominent outside choreographers.

From 1970 on, dance departments began to emerge in a number of Canadian universities, bolstering performance training with studies in dance composition, history, theory, criticism, therapy and anthropology. The first of these, founded by Grant Strate at York University in Toronto, was influential in shaping the future development of Canadian dance. Many of its graduates, among them Christopher House, Carol Anderson, Holly Small, Jennifer Mascall, Tedd Senmon Robinson and Conrad Alexandrowicz, have moved on to important careers.

Strate addressed a chronic need to train new choreographers by launching the first of an irregular series of national choreographic seminars at York. Although formal opportunities for the training of choreographers are rare throughout the dance world, in Canada various mentoring initiatives, such as those provided by Le Groupe de la Place Royale and Toronto's Ballet Jörgen, together with a range of choreographic workshops held by companies across the country, have helped develop a new generation of Canadian dancemakers.

The expansive era in Canadian dance, which in the 1960s saw the birth of several companies, including Ruth Carse's Alberta Ballet in Edmonton, quickened in pace during the 1970s and beyond.

In Toronto, such popular contemporary troupes as the Danny Grossman Dance Theatre and Desrosiers Dance Theatre emerged in 1977 and 1980 respectively. In Vancouver, the Anna Wyman Dancers was founded in 1971 and in 1974, after almost a decade of hand-to-mouth existence, Paula Ross Dancers, whose aesthetic included ballet and modern genres to facilitate the exploration of social themes such as the disenfranchised Aboriginal community,began to receive government funding.

Montréal began to gather momentum as a powerhouse of dance creativity with the founding in 1968 of Le Groupe Nouvelle Aire, a number of whose associates and members, notably Édouard Lock (La La La Human Steps), Ginette Laurin (O Vertigo) and Paul-André Fortier (Fortier Danse Création), went on to found companies of their own. Montréal's importance in the world of contemporary dance was vividly symbolized by the launching in 1985 of the ambitious, now biennial Festival International de Nouvelle Danse.

Later, the formation of EDAM (Experimental Dance and Music) in Vancouver by Peter Bingham (who still heads the organization), Peter Ryan, Lola MacLaughlin, Ahmed Hassan, Jennifer Mascall, Barbara Bourget, and Jay Hirabayashi would lead to several off-shoots which became and continue to serve as fixtures in the Vancouver dance community. Lola Dance (which continued until MacLaughlin’s passing), Kokoro Dance (Hirabayashi and Bourget), Mascall Dance (Jennifer Mascall), and EDAM (Peter Bingham) became educational and performative homes for a new generation of emerging artists.

In 1973, the Dance in Canada Association (DICA) was established as an all-embracing national service organization to create a sense of community and bring some focus to the variety of dance endeavours occurring across the country. Through its newsletters, magazine and annual conferences, which included an eclectic festival of performances, DICA sought to unite the community. Instead, it inadvertently split asunder.

Growing Pains

In the mid-1970s, The Canada Council and similar provincial public funding bodies found their resources squeezed by a slumping economy and ever-increasing demand for support. The dynamic dance community that arguably could not have come into being without Canada Council funding now angrily turned on its public patron, accusing it of favouritism, elitism, and trying to engineer the regional and aesthetic evolution of the art form. DICA led the charge and became seen as the lobby group of the excluded and underprivileged. In response, the eight "senior" institutions receiving continuing Council support broke away to protect their own interest in a new service organization, the Canadian Association of Professional Dance Organizations (CAPDO). The rifts in the Canadian dance community, which exploded wide open in a shouting match at the 1977 DICA conference in Winnipeg, took years to heal. When they did, it was because the expansive and turbulent era had passed and dance as a buoyant art form was increasingly facing challenges from all quarters. DICA struggled on, with diminishing effectiveness, into the early 1990s. Its enduring legacy is the Canada Dance Festival, launched in 1987 as a more carefully curated successor to the sometimes ramshackle performances formerly accompanying the annual DICA conferences. The festival continues biennially under the auspices of the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. CAPDO survived a while longer but, as the funding for arts service organizations withered, it too eventually went into abeyance.

This is not to say that professional organizations for dance in Canada died with the DICA. Indeed, from the 1980s to the new millennium, Canada saw the establishment and perseverance of organizations and individuals that continue to contribute to the dance milieu in the form of publishing, teaching, supporting retired dancers, and capturing and archiving Canadian dance history. The Canadian dance scene has sought to legitimize and professionalize via the establishment of administrative and collective interest organizations, among them the Canadian Alliance of Dance Artists (CADA) and The Canada Dance Assembly (CDA). The Dancer Transition Resource Centre (DTRC), with chapters in Toronto, Vancouver, and Montréal, aids retiring dancers in transitioning into new careers. The Canadian Society for Dance Studies, an academic and research-based organization, is dedicated to promoting Canadian dance scholarship and hosts bi-annual conferences in Canada’s major cities. Another example is Dance Collection Danse, an archive and living museum of Canada’s national dance artifacts whose mission is to preserve and disseminate a large chapter of the nation’s cultural history which would otherwise go unnoticed. These institutions at once support discussion and offer resources for dance artists and administrators to help ensure a lasting and healthy dance ecology.

Canada is also host to several academic dance programs. Concordia University, Simon Fraser University, Ryerson University, George Brown College, and York University are some examples of institutions which offer degrees and/or certificates in dance performance and dance studies, and are host to faculties submerged in original research, the publication of new works, and the creation of new choreographies. York University’s dance program, the first to offer a PhD in dance studies in Canada and host to a BA, BFA, MFA and MA in the same field, has a long history of impacting upon the growth of the dance milieu with its active faculty and long list of successful graduates. The York Dance Review, published in the 1970s, was a vehicle through which dance writers honed their voices, and added to the discussion put forward by newspaper dance journalists of the time such as Michael Crabb, William Littler, Laretta Thistle, Lawrence Gradus, John Fraser, Graham Jackson, Susan Cohen, and later Paula Citron, Carol Anderson, Dierdre Kelly, Megan Andrews, Philip Szporer, Kathleen Smith, and others. Canada has seen its fair share of Canadian dance publications featuring issue-driven articles and reviews. Over the course of three decades, dance specific sources have included Dance Collection Danse Magazine, Dance International, Dance in Canada, Dance Connection, and The Dance Current, the latter of which remains the nation’s foremost source for news and views related to the dance milieu in Canada.

The Contemporary Scene

Despite the deflation of the international dance boom and the disappearance of a number of smaller Canadian companies and schools such as Regina Modern Dance Works, Vancouver’s Main Dance, Toronto Independent Dance Enterprise), the Paula Ross Dancers and The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre, theatrical dance in Canada has continued to evolve and diversify.Since the production of art is a reflection of a culture or society, and the face of Canadian culture continues to change with the influx of different world views, cultures, and social practices, the contemporary dance scene reflects those changes as well. It has done so by learning to scale down and adapt without the sacrifice of artistic vitality or innovation.

Solo artists such as Montréal's Marie Chouinard and Margie Gillis, Vancouver’s Crystal Pite, and Toronto's Peggy Baker, have each won international acclaim for their choreographic output. Ambitious independent dancer/choreographers and collectives continue to survive and prosper artistically by working independently, outside the costly and often cumbersome bounds of a formal company organization. This new breed has grown impatient with traditional aesthetic distinctions and delves freely into a pool of creative possibilities, cross-pollinating with all types of dance, from jazz and hip-hop to the potent, minimalist expressiveness of Japanese butoh and various Asian traditions. The independents have freely explored useful collaborations with experimental musicians, filmmakers and designers. The work of these enterprising dance creators has been celebrated in Toronto's annual Fringe Festival, Vancouver’s Dancing on the Edge, and Dusk Dances, as well as in similar smaller events in other cities.

By the early 21st century, continuing funding problems and shifting audience preferences had dampened the growth of professional Canadian dance. Yet the nation's dance culture has become creatively richer with the emergence and growing acceptance of dance traditions beyond the European and North American mainstream, particularly those of South Asia. Menaka Thakkar, Rina Singha, Lata Pada, Hari Krishnan, Jai Govinda, Janak Khendry, and Roger Sinha have all helped to win wide acceptance for the traditions of South Asian dance and have willingly explored ways in which it can fruitfully interrelate with Western forms.On the West Coast, dance companies such as Wen Wei Dance, Kokoro Dance and Co. ERASAGA have at times explored the fusion of the Pacific Rim, European and North American culture that characterizes modern Vancouver.Ukrainian (such as Alberta’s Shumka Dancers) and Afro-Caribbean dance (Toronto’s C.O.B.A and Ballet Creole), Spanish flamenco (Vancouver’s Flamenco Rosario and Toronto’s Esmeralda Enrique Spanish Dance Company) and even belly-dancing have all asserted their rightful place in the mosaic that constitutes the artistic face of Canadian dance today. While once considered well outside the realm of the English-French dance aesthetic of mid-20th-Century Canada, these practitioners are now considered immoveable fixtures in the dance landscape of the nation.

Dance in Canada is the cumulative body of centuries of cultural importation, adaptation and assimilation. Canada can now offer its dance artists both the training and performance opportunities that allow them to pursue fulfilling and diverse careers within their own country, a dramatic contrast to the situation that existed half a century ago. Now, Canadian dance artists have the opportunity to practice and specialize in multiple dance genres, from ballet to bharata natyam. This accessibility to multicultural forms is indicative of Canada's national openness and its diverse population, particularly in major city centres such as Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. And too, if Canada has not bred anything that can truly be described as a national style, in its extraordinary variety and openness to new ideas Canadian dance is as vibrant and vital as any in the world.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom