The Company of New France, or Company of One Hundred Associates (Compagnie des Cent-Associés) as it was more commonly known, was formed in France in 1627. Its purpose was to increase New France’s population while enjoying a monopoly on almost all colonial trade. It took bold steps but suffered many setbacks. The company folded in 1663. It earned little return on its investment, though it helped establish New France as a viable colony.

Founding and Purpose

In the 16th century, France, Spain, Portugal and Britain were competing for dominance in Europe and around the world. Part of that competition involved establishing colonies in North America. (See also British North America.) French explorers such as Jacques Cartier arrived in what would become Canada in the 1530s. In 1608, French explorer and cartographer Samuel de Champlain created a small settlement at what is now Quebec City. He also worked with numerous First Nations to create a fur trading network that extended to the Ottawa River and the Great Lakes.

France’s King Louis XIII was primarily concerned with domestic issues and the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). He gave private companies the power to organize and rule New France and to earn profits from fishing and the lucrative fur trade. By the mid-1620s, only about 55 people of European descent, mostly single young men, lived in New France.

The colony’s unrealized potential was recognized by Cardinal Richelieu, a powerful Catholic bishop and France’s secretary of state. He exerted enormous influence over the King and French affairs. In 1626, Richelieu decided that the best way to build the colony was to abolish the rival trading companies and create one new company.

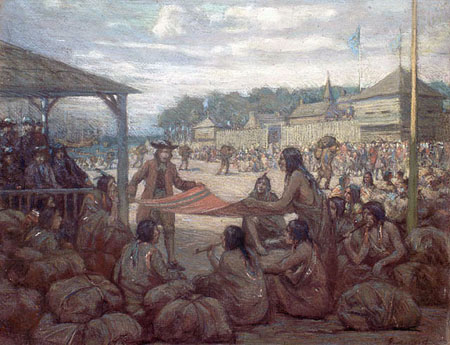

Richelieu gathered 100 merchants, financiers and public-office holders. They paid 3,000 livres each to underwrite the Company of New France. The round number of investors led to the company being popularly referred to as the Company of One Hundred Associates (Compagnie des Cent-Associés). Richelieu was associate No. 1 and Champlain was No. 52. The company was run by 12 directors. It was granted title to land stretching from Florida to the Arctic and as far west as was then known. Its mandate was to transport 4,000 settlers to New France by 1653 and support them for their first three years. In return, the company was to exert monopoly control over all trade except cod and whales

Failed Efforts

France and England had been at war since 1625, which made ocean travel quite dangerous. Nonetheless, in the spring of 1628, the company dispatched a ship carrying food and provisions to Quebec and then four more ships carrying 400 colonists. Heavily armed British ships captured the French supply ship and burned French settlements along the St. Lawrence River. The British leader, David Kirke, sent a message to Champlain demanding Quebec’s surrender. Champlain refused.

The French ships attempted to pass the British fleet under a cover of fog, but they were spotted. A battle ensued, ending with the capture of the Hundred Associates’ ships. Kirke sent passengers and crew back to France and returned to England. The company’s first venture was an abject failure.

Kirke returned the next year with a bigger fleet. In July 1629, he captured all of New France, including Quebec. The British Company of Adventurers to Canada took control of the fish and fur trade. Champlain was taken to Britain. However, upon his arrival, he discovered that the French-English war had ended in April, three months before Quebec’s fall. Working with the French ambassador, he convinced British authorities that taking Quebec had been illegal. He argued that Britain should respect the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye; it had ended the war and stipulated that New France, including Acadia, must be immediately returned to French control. Britain’s King Charles I eventually agreed.

The loss of New France had left the Company of One Hundred Associates with no profits and huge debts. Only 30,000 livres remained of the original 300,000 investment. The directors nonetheless borrowed more money and, in 1630, organized a fleet of five ships to go to Quebec. However, Charles I protested that the ships were armed and so constituted an act of war. Louis XIII agreed and had them stopped. The scuttled voyage was yet another failure for the company.

Subsidiaries

The company was then reorganized into a number of subsidiaries, which undertook more limited ventures. Beginning in 1631, company subsidiaries developed French forts and settlements at Cape Breton Island’s Fort Sainte-Anne; another near the site of present-day Saint John, New Brunswick; one more at the southern tip of Nova Scotia on Cape Sable Island; and another at Miscou Island, south of the Gaspé Peninsula. All successfully rid the areas of remaining English settlers and traders and re-established French fishing and trading rights. All led to permanent and growing French settlements.;

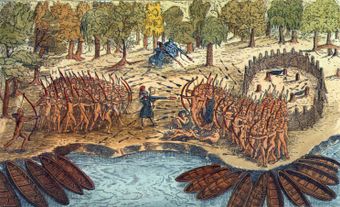

In 1632, the company created another subsidiary that led to the evacuation of English traders who were still illegally operating in Quebec. Richelieu appointed Champlain, France’s most visionary and capable colonial administrator, to again take command. The next spring, the company commissioned three ships carrying provisions and 150 settlers to rebuild Quebec. Champlain oversaw the construction of buildings and roads. He rid the St. Lawrence of unlicensed French and British traders and re-established relations with the Montagnais, Huron, Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Algonquin nations.

Every spring, the company sent more French immigrants to Quebec. Settlers in the towns and on seigneurial farms along the St. Lawrence were no longer single men but families, eager to establish permanent homes. With them came more Jesuits, who had first arrived in 1625. They established Quebec as a Catholic society and spread their influence, sometimes with unfortunate consequences, among the Indigenous peoples.

The Company’s Demise

While New France was growing, the company continued to lose money. In 1645, it retained ownership of the land and control of colonial administration but surrendered its fur trade monopoly to the Canadian Compagnie des Habitants in return for 1,000 beaver pelts a year. The company’s debts were overwhelming. By the late 1650s, the company had only 36 investors. It repeatedly appealed to the king for help, but all petitions were rejected.

The company ended operations in 1663. With the company’s demise, New France came under the direct management of the French crown, which began taking other steps to populate the colony. (See Filles du Roi.)

See also: New France: Collection; Fur Trade: Timeline; Exploration: Timeline; Colonization: Timeline; Samuel de Champlain: Timeline.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom